A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on the |

| Great Recession |

|---|

| Timeline |

The 2007–2008 financial crisis, or the global financial crisis (GFC), was the most severe worldwide economic crisis since the Great Depression. Predatory lending in the form of subprime mortgages targeting low-income homebuyers,[1] excessive risk-taking by global financial institutions,[2] a continuous buildup of toxic assets within banks, and the bursting of the United States housing bubble culminated in a "perfect storm", which led to the Great Recession.

Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) tied to American real estate, as well as a vast web of derivatives linked to those MBS, collapsed in value. Financial institutions worldwide suffered severe damage,[3] reaching a climax with the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008, and a subsequent international banking crisis.[4]

The preconditioning for the financial crisis was complex and multi-causal.[5][6][7] Almost two decades prior, the U.S. Congress had passed legislation encouraging financing for affordable housing.[8] However, in 1999, parts of the Glass-Steagall legislation, which had been adopted in 1933, were repealed, permitting financial institutions to commingle their commercial (risk-averse) and proprietary trading (risk-taking) operations.[9] Arguably the largest contributor to the conditions necessary for financial collapse was the rapid development in predatory financial products which targeted low-income, low-information homebuyers who largely belonged to racial minorities.[10] This market development went unattended by regulators and thus caught the U.S. government by surprise.[11]

After the onset of the crisis, governments deployed massive bail-outs of financial institutions and other palliative monetary and fiscal policies to prevent a collapse of the global financial system.[12] In the U.S., the October 3, $800 billion Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 failed to slow the economic free-fall, but the similarly-sized American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, which included a substantial payroll tax credit, saw economic indicators reverse and stabilize less than a month after its February 17 enactment.[13] The crisis sparked the Great Recession which resulted in increases in unemployment[14] and suicide,[15] and decreases in institutional trust[16] and fertility,[17] among other metrics. The recession was a significant precondition for the European debt crisis.

In 2010, the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was enacted in the US as a response to the crisis to "promote the financial stability of the United States".[18] The Basel III capital and liquidity standards were also adopted by countries around the world.[19][20]

Background

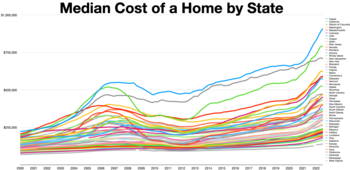

The crisis sparked the Great Recession, which, at the time, was the most severe global recession since the Great Depression.[22][23][24][25][26] It was also followed by the European debt crisis, which began with a deficit in Greece in late 2009, and the 2008–2011 Icelandic financial crisis, which involved the bank failure of all three of the major banks in Iceland and, relative to the size of its economy, was the largest economic collapse suffered by any country in history.[27] It was among the five worst financial crises the world had experienced and led to a loss of more than $2 trillion from the global economy.[28][29] U.S. home mortgage debt relative to GDP increased from an average of 46% during the 1990s to 73% during 2008, reaching $10.5 (~$14.6 trillion in 2023) trillion.[30] The increase in cash out refinancings, as home values rose, fueled an increase in consumption that could no longer be sustained when home prices declined.[31][32][33] Many financial institutions owned investments whose value was based on home mortgages such as mortgage-backed securities, or credit derivatives used to insure them against failure, which declined in value significantly.[34][35][36] The International Monetary Fund estimated that large U.S. and European banks lost more than $1 trillion on toxic assets and from bad loans from January 2007 to September 2009.[37]

Lack of investor confidence in bank solvency and declines in credit availability led to plummeting stock and commodity prices in late 2008 and early 2009.[38] The crisis rapidly spread into a global economic shock, resulting in several bank failures.[39] Economies worldwide slowed during this period since credit tightened and international trade declined.[40] Housing markets suffered and unemployment soared, resulting in evictions and foreclosures. Several businesses failed.[41][42] From its peak in the second quarter of 2007 at $61.4 trillion, household wealth in the United States fell $11 trillion, to $50.4 trillion by the end of the first quarter of 2009, resulting in a decline in consumption, then a decline in business investment.[43][44] In the fourth quarter of 2008, the quarter-over-quarter decline in real GDP in the U.S. was 8.4%.[45] The U.S. unemployment rate peaked at 11.0% in October 2009, the highest rate since 1983 and roughly twice the pre-crisis rate. The average hours per work week declined to 33, the lowest level since the government began collecting the data in 1964.[46][47]

The economic crisis started in the U.S. but spread to the rest of the world.[41] U.S. consumption accounted for more than a third of the growth in global consumption between 2000 and 2007 and the rest of the world depended on the U.S. consumer as a source of demand.[citation needed][48][49] Toxic securities were owned by corporate and institutional investors globally. Derivatives such as credit default swaps also increased the linkage between large financial institutions. The de-leveraging of financial institutions, as assets were sold to pay back obligations that could not be refinanced in frozen credit markets, further accelerated the solvency crisis and caused a decrease in international trade. Reductions in the growth rates of developing countries were due to falls in trade, commodity prices, investment and remittances sent from migrant workers (example: Armenia[50]). States with fragile political systems feared that investors from Western states would withdraw their money because of the crisis.[51]

As part of national fiscal policy response to the Great Recession, governments and central banks, including the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of England, provided then-unprecedented trillions of dollars in bailouts and stimulus, including expansive fiscal policy and monetary policy to offset the decline in consumption and lending capacity, avoid a further collapse, encourage lending, restore faith in the integral commercial paper markets, avoid the risk of a deflationary spiral, and provide banks with enough funds to allow customers to make withdrawals. [52] In effect, the central banks went from being the "lender of last resort" to the "lender of only resort" for a significant portion of the economy. In some cases the Fed was considered the "buyer of last resort".[53][54][55][56][57] During the fourth quarter of 2008, these central banks purchased US$2.5 (~$3.47 trillion in 2023) trillion of government debt and troubled private assets from banks. This was the largest liquidity injection into the credit market, and the largest monetary policy action in world history. Following a model initiated by the 2008 United Kingdom bank rescue package,[58][59] the governments of European nations and the United States guaranteed the debt issued by their banks and raised the capital of their national banking systems, ultimately purchasing $1.5 trillion newly issued preferred stock in major banks.[44] The Federal Reserve created then-significant amounts of new currency as a method to combat the liquidity trap.[60]

Bailouts came in the form of trillions of dollars of loans, asset purchases, guarantees, and direct spending.[61] Significant controversy accompanied the bailouts, such as in the case of the AIG bonus payments controversy, leading to the development of a variety of "decision making frameworks", to help balance competing policy interests during times of financial crisis.[62] Alistair Darling, the U.K.'s Chancellor of the Exchequer at the time of the crisis, stated in 2018 that Britain came within hours of "a breakdown of law and order" the day that Royal Bank of Scotland was bailed-out.[63] Instead of financing more domestic loans, some banks instead spent some of the stimulus money in more profitable areas such as investing in emerging markets and foreign currencies.[64]

In July 2010, the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was enacted in the United States to "promote the financial stability of the United States".[65] The Basel III capital and liquidity standards were adopted worldwide.[66] Since the 2008 financial crisis, consumer regulators in America have more closely supervised sellers of credit cards and home mortgages in order to deter anticompetitive practices that led to the crisis.[67]: 1311

At least two major reports on the causes of the crisis were produced by the U.S. Congress: the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission report, released January 2011, and a report by the United States Senate Homeland Security Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations entitled Wall Street and the Financial Crisis: Anatomy of a Financial Collapse, released April 2011.

In total, 47 bankers served jail time as a result of the crisis, over half of which were from Iceland, where the crisis was the most severe and led to the collapse of all three major Icelandic banks.[68] In April 2012, Geir Haarde of Iceland became the only politician to be convicted as a result of the crisis.[69][70] Only one banker in the United States served jail time as a result of the crisis, Kareem Serageldin, a banker at Credit Suisse who was sentenced to 30 months in jail and returned $24.6 million in compensation for manipulating bond prices to hide $1 billion of losses.[71][68] No individuals in the United Kingdom were convicted as a result of the crisis.[72][73] Goldman Sachs paid $550 million to settle fraud charges after allegedly anticipating the crisis and selling toxic investments to its clients.[74]

With fewer resources to risk in creative destruction, the number of patent applications was flat, compared to exponential increases in patent application in prior years.[75]

Typical American families did not fare well, nor did the "wealthy-but-not-wealthiest" families just beneath the pyramid's top.[76][77][78] However, half of the poorest families in the United States did not have wealth declines at all during the crisis because they generally did not own financial investments whose value can fluctuate. The Federal Reserve surveyed 4,000 households between 2007 and 2009, and found that the total wealth of 63% of all Americans declined in that period and 77% of the richest families had a decrease in total wealth, while only 50% of those on the bottom of the pyramid suffered a decrease.[79][80][81]

Timeline

The following is a timeline of the major events of the financial crisis, including government responses, and the subsequent economic recovery.[82][83][84][85]

Pre-2007

- May 19, 2005: Fund manager Michael Burry closed a credit default swap against subprime mortgage bonds with Deutsche Bank valued at $60 million – the first such CDS. He projected they would become volatile within two years of the low "teaser rate" of the mortgages expiring.[86][87]

- 2006: After years of above-average price increases, housing prices peaked and mortgage loan delinquency rose, leading to the United States housing bubble.[88][89] Due to increasingly lax underwriting standards, one-third of all mortgages in 2006 were subprime or no-documentation loans,[90] which comprised 17 percent of home purchases that year.[91]

- May 2006: JPMorgan warns clients of housing downturn, especially sub-prime.[92]

- August 2006: The yield curve inverted, signaling a recession was likely within a year or two.[93]

- November 2006: UBS sounded "the alarm about an impending crisis in the U.S. housing market" [92]

2007 (January–August)

- February 27, 2007: Stock prices in China and the U.S. fell by the most since 2003 as reports of a decline in home prices and durable goods orders stoked growth fears, with Alan Greenspan predicting a recession.[94] Due to increased delinquency rates in subprime lending, Freddie Mac said that it would stop investing in certain subprime loans.[95]

- April 2, 2007: New Century, an American real estate investment trust specializing in subprime lending and securitization, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. This propagated the subprime mortgage crisis.[96][97][91][98][99]

- June 20, 2007: After receiving margin calls, Bear Stearns bailed out two of its hedge funds with $20 billion of exposure to collateralized debt obligations including subprime mortgages.[100]

- July 19, 2007: The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) closed above 14,000 for the first time at 14,000.41.[101]

- July 30, 2007: IKB Deutsche Industriebank, the first banking casualty of the crisis, announces its bailout by German public financial institution KfW.[102]

- July 31, 2007: Bear Stearns liquidated the two hedge funds.[98]

- August 6, 2007: American Home Mortgage filed bankruptcy.[98]

- August 9, 2007: BNP Paribas blocked withdrawals from three of its hedge funds with a total of $2.2 billion in assets under management, due to "a complete evaporation of liquidity", making valuation of the funds impossible – a clear sign that banks were refusing to do business with each other.[99][103][104]

- August 16, 2007: The DJIA closes at 12,945.78 after falling 12 out of the previous 20 trading days following its peak. It had fallen 1,164.63 or 8.3%.[101]

2007 (September–December)

- September 14, 2007: Northern Rock, a medium-sized and highly leveraged British bank, received support from the Bank of England.[105] This led to investor panic and a bank run.[106]

- September 18, 2007: The Federal Open Market Committee began reducing the federal funds rate from its peak of 5.25% in response to worries about liquidity and confidence.[107][108]

- September 28, 2007: NetBank suffered from bank failure and filed bankruptcy due to exposure to home loans.[109]

- October 9, 2007: The DJIA hit its peak closing price of 14,164.53.[110]

- October 15, 2007: Citigroup, Bank of America, and JPMorgan Chase announced plans for the $80 billion Master Liquidity Enhancement Conduit to provide liquidity to structured investment vehicles. The plan was abandoned in December.[111]

- December 2007: Unemployment in the US hit 5%.[112][not specific enough to verify]

- December 12, 2007: The Federal Reserve instituted the Term auction facility to supply short-term credit to banks with sub-prime mortgages.[113]

- December 17, 2007: Delta Financial Corporation filed bankruptcy after failing to securitize subprime loans.[114]

- December 19, 2007: the Standard and Poor's rating agency downgrades the ratings of many monoline insurers which pay out bonds that fail.[citation needed]

2008 (Jan - Aug)

- January 11, 2008: Bank of America agreed to buy Countrywide Financial for $4 billion in stock.[115]

- January 18, 2008: Stock markets fell to a yearly low as the credit rating of Ambac, a bond insurance company, was downgraded. Meanwhile, an increase in the amount of withdrawals causes Scottish Equitable to implement up to 12 month delays on people wanting to withdraw money.[116]

- January 21, 2008: As US markets were closed for Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the FTSE 100 Index in the United Kingdom tumbled 323.5 points or 5.5% in its largest crash since the September 11 attacks.[117]

- January 22, 2008: The US Federal Reserve cut interest rates by 0.75% to stimulate the economy, the largest drop in 25 years and the first emergency cut since 2001.[117]

- January 2008: U.S. stocks had the worst January since 2000 over concerns about the exposure of companies that issue bond insurance.[118]

- February 13, 2008: The Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 was enacted, which included a tax rebate.[119][120]

- February 22, 2008: The nationalisation of Northern Rock was completed.[106]

- March 5, 2008: The Carlyle Group received margin calls on its mortgage bond fund.[121]

- March 17, 2008: Bear Stearns, with $46 billion of mortgage assets that had not been written down and $10 trillion in total assets, faced bankruptcy; instead, in its first emergency meeting in 30 years, the Federal Reserve agreed to guarantee its bad loans to facilitate its acquisition by JPMorgan Chase for $2/share. A week earlier, the stock was trading at $60/share and a year earlier it traded for $178/share. The buyout price was increased to $10/share the following week.[122][123][124]

- March 18, 2008: In a contentious meeting, the Federal Reserve cut the federal funds rate by 75 basis points, its 6th cut in 6 months.[125] It also allowed Fannie Mae & Freddie Mac to buy $200 billion in subprime mortgages from banks. Officials thought this would contain the possible crisis. The U.S. dollar weakened and commodity prices soared.[data missing][126][127][128]

- Late June 2008: Despite the U.S. stock market falling to a 20% drop off its highs, commodity-related stocks soared as oil traded above $140/barrel for the first time and steel prices rose above $1,000 per ton. Worries about inflation combined with strong demand from China encouraged people to invest in commodities during the 2000s commodities boom.[129][130]

- July 11, 2008: IndyMac failed. Oil prices peaked at $147.50[131][117]

- July 30, 2008: The Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 was enacted.[132]

- August 2008: Unemployment hit 6% in the US.[112]

2008 (September)

- September 7, 2008: The Federal takeover of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac was implemented.[133]

- September 15, 2008: After the Federal Reserve declined to guarantee its loans as it did for Bear Stearns, the Bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers led to a 504.48-point (4.42%) drop in the DJIA, its worst decline in seven years. To avoid bankruptcy, Merrill Lynch was acquired by Bank of America for $50 billion in a transaction facilitated by the government.[134] Lehman had been in talks to be sold to either Bank of America or Barclays but neither bank wanted to acquire the entire company.[135]

- September 16, 2008: The Federal Reserve took over American International Group with $85 billion in debt and equity funding. The Reserve Primary Fund "broke the buck" as a result of its exposure to Lehman Brothers securities.[136]

- September 17, 2008: Investors withdrew $144 billion from U.S. money market funds, the equivalent of a bank run on money market funds, which frequently invest in commercial paper issued by corporations to fund their operations and payrolls, causing the short-term lending market to freeze. The withdrawal compared to $7.1 billion in withdrawals the week prior. This interrupted the ability of corporations to rollover their short-term debt. The U.S. government extended insurance for money market accounts analogous to bank deposit insurance via a temporary guarantee[137] and with Federal Reserve programs to purchase commercial paper.

- September 18, 2008: In a dramatic meeting, United States Secretary of the Treasury Henry Paulson and Chair of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke met with Speaker of the United States House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi and warned that the credit markets were close to a complete meltdown. Bernanke requested a $700 billion fund to acquire toxic mortgages and reportedly told them: "If we don't do this, we may not have an economy on Monday".[138]

- September 19, 2008: The Federal Reserve created the Asset Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility to temporarily insure money market funds and allow the credit markets to continue operating.[citation needed]

- September 20, 2008: Paulson requested the U.S. Congress authorize a $700 billion fund to acquire toxic mortgages, telling Congress "If it doesn't pass, then heaven help us all".[139]

- September 21, 2008: Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley converted from investment banks to bank holding companies to increase their protection by the Federal Reserve.[140][141][142][143]

- September 22, 2008: MUFG Bank acquired 20% of Morgan Stanley.[144]

- September 23, 2008: Berkshire Hathaway made a $5 billion investment in Goldman Sachs.[145]

- September 26, 2008: Washington Mutual went bankrupt and was seized by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation after a bank run in which panicked depositors withdrew $16.7 billion in 10 days.[146]

- September 29, 2008: By a vote of 225–208, with most Democrats in support and Republicans against, the House of Representatives rejected the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, which included the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program. In response, the DJIA dropped 777.68 points, or 6.98%, then the largest point drop in history. The S&P 500 Index fell 8.8% and the Nasdaq Composite fell 9.1%.[147] Several stock market indices worldwide fell 10%. Gold prices soared to $900/ounce. The Federal Reserve doubled its credit swaps with foreign central banks as they all needed to provide liquidity. Wachovia reached a deal to sell itself to Citigroup; however, the deal would have made shares worthless and required government funding.[148]

- September 30, 2008: President George W. Bush addressed the country, saying "Congress must act. ... Our economy is depending on decisive action from the government. The sooner we address the problem, the sooner we can get back on the path of growth and job creation". The DJIA rebounded 4.7%.[149]

2008 (October)

- October 1, 2008: The U.S. Senate passed the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008.[150]

- October 2, 2008: Stock market indices fell 4% as investors were nervous ahead of a vote in the U.S. House of Representatives on the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008.[151]

- October 3, 2008: The House of Representatives passed the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008.[152] Bush signed the legislation that same day.[153] Wachovia reached a deal to be acquired by Wells Fargo in a deal that did not require government funding.[154]

- October 6–10, 2008: From October 6–10, 2008, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) closed lower in all five sessions. Volume levels were record-breaking. The DJIA fell 1,874.19 points, or 18.2%, in its worst weekly decline ever on both a points and percentage basis. The S&P 500 fell more than 20%.[155]

- October 7, 2008: In the U.S., per the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation increased deposit insurance coverage to $250,000 per depositor.[156]

- October 8, 2008: The Indonesian stock market halted trading after a 10% drop in one day.[158] Global central banks held emergency meetings and coordinated interest rate cuts before the US stock markets opened.[159]

- October 11, 2008: The head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) warned that the world financial system was teetering on the "brink of systemic meltdown".[160]

- October 14, 2008: Having been suspended for three successive trading days (October 9, 10 and 13), the Icelandic stock market reopened on October 14, with the main index, the OMX Iceland 15, closing at 678.4, which was about 77% lower than the 3,004.6 at the close on October 8, after the value of the three big banks, which had formed 73.2% of the value of the OMX Iceland 15, had been set to zero, leading to the 2008–2011 Icelandic financial crisis.[161] The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation created the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program to guarantee the senior debt of all FDIC-insured institutions through June 30, 2009.[162]

- October 16, 2008: A rescue plan was unveiled for Swiss banks UBS AG and Credit Suisse.[163]

- October 24, 2008: Many of the world's stock exchanges experienced the worst declines in their history, with drops of around 10% in most indices.[164] In the U.S., the DJIA fell 3.6%, although not as much as other markets.[165] The United States dollar and Japanese yen and the Swiss franc soared against other major currencies, particularly the British pound and Canadian dollar, as world investors sought safe havens. A currency crisis developed, with investors transferring vast capital resources into stronger currencies, leading many governments of emerging economies to seek aid from the International Monetary Fund.[166][167] Later that day, the deputy governor of the Bank of England, Charlie Bean, suggested that "This is a once in a lifetime crisis, and possibly the largest financial crisis of its kind in human history".[168] In a transaction pushed by regulators, PNC Financial Services agreed to acquire National City Corp.[169]

2008 (November–December)

- November 6, 2008: The IMF predicted a worldwide recession of −0.3% for 2009. On the same day, the Bank of England and the European Central Bank, respectively, reduced their interest rates from 4.5% to 3%, and from 3.75% to 3.25%.[170]

- November 10, 2008: American Express converted to a bank holding company.[171]

- November 20, 2008: Iceland obtained an emergency loan from the International Monetary Fund after the failure of banks in Iceland resulted in a devaluation of the Icelandic króna and threatened the government with bankruptcy.[172]

- November 25, 2008: The Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility was announced.[173]

- November 29, 2008: Economist Dean Baker observed:

There is a really good reason for tighter credit. Tens of millions of homeowners who had substantial equity in their homes two years ago have little or nothing today. Businesses are facing the worst downturn since the Great Depression. This matters for credit decisions. A homeowner with equity in her home is very unlikely to default on a car loan or credit card debt. They will draw on this equity rather than lose their car and/or have a default placed on their credit record. On the other hand, a homeowner who has no equity is a serious default risk. In the case of businesses, their creditworthiness depends on their future profits. Profit prospects look much worse in November 2008 than they did in November 2007 ... While many banks are obviously at the brink, consumers and businesses would be facing a much harder time getting credit right now even if the financial system were rock solid. The problem with the economy is the loss of close to $6 trillion in housing wealth and an even larger amount of stock wealth.[174]

- December 1, 2008: The NBER announced the US was in a recession and had been since December 2007. The Dow tumbled 679.95 points or 7.8% on the news.[175][101]

- December 6, 2008: The 2008 Greek riots began, sparked in part by economic conditions in the country.[citation needed]

- December 16, 2008: The federal funds rate was lowered to zero percent.[176]

- December 20, 2008: Financing under the Troubled Asset Relief Program was made available to General Motors and Chrysler.[177]

2009

- January 6, 2009: Citi claimed that Singapore would experience "the most severe recession in Singapore's history" in 2009. In the end the economy grew in 2009 by 0.1% and in 2010 by 14.5%.[178][179][180]

- January 20–26, 2009: The 2009 Icelandic financial crisis protests intensified and the Icelandic government collapsed.[181]

- February 13, 2009: Congress approved the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, a $787 billion economic stimulus package. President Barack Obama signed it February 17.[182][13][183][184]

- February 20, 2009: The DJIA closed at a 6-year low amidst worries that the largest banks in the United States would have to be nationalized.[185]

- February 27, 2009: The DJIA closed its lowest value since 1997 as the U.S. government increased its stake in Citigroup to 36%, raising further fears of nationalization and a report showed that GDP shrank at the sharpest pace in 26 years.[186]

- Early March 2009: The drop in stock prices was compared to that of the Great Depression.[187][188]

- March 3, 2009: President Obama stated that "Buying stocks is a potentially good deal if you've got a long-term perspective on it".[189]

- March 6, 2009: The Dow Jones hit its lowest level of 6,469.95, a drop of 54% from its peak of 14,164 on October 9, 2007, over a span of 17 months, before beginning to recover.[190]

- March 10, 2009: Shares of Citigroup rose 38% after the CEO said that the company was profitable in the first two months of the year and expressed optimism about its capital position going forward. Major stock market indices rose 5–7%, marking the bottom of the stock market decline.[191]

- March 12, 2009: Stock market indices in the U.S. rose another 4% after Bank of America said it was profitable in January and February and would likely not need more government funding. Bernie Madoff was convicted.[192]

- First quarter of 2009: For the first quarter of 2009, the annualized rate of decline in GDP was 14.4% in Germany, 15.2% in Japan, 7.4% in the UK, 18% in Latvia,[193] 9.8% in the Euro area and 21.5% for Mexico.[41]

- April 2, 2009: Unrest over economic policy and bonuses paid to bankers resulted in the 2009 G20 London summit protests.

- April 10, 2009: Time magazine declared "More Quickly Than It Began, The Banking Crisis Is Over".[194]

- April 29, 2009: The Federal Reserve projected GDP growth of 2.5–3% in 2010; an unemployment plateau in 2009 and 2010 around 10% with moderation in 2011; and inflation rates around 1–2%.[195]

- May 1, 2009: People protested economic conditions globally during the 2009 May Day protests.

- May 20, 2009: President Obama signed the Fraud Enforcement and Recovery Act of 2009.

- June 2009: The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) declared June 2009 as the end date of the U.S. recession.[196] The Federal Open Market Committee release in June 2009 stated:

... the pace of economic contraction is slowing. Conditions in financial markets have generally improved in recent months. Household spending has shown further signs of stabilizing but remains constrained by ongoing job losses, lower housing wealth, and tight credit. Businesses are cutting back on fixed investment and staffing but appear to be making progress in bringing inventory stocks into better alignment with sales. Although economic activity is likely to remain weak for a time, the Committee continues to anticipate that policy actions to stabilize financial markets and institutions, fiscal and monetary stimulus, and market forces will contribute to a gradual resumption of sustainable economic growth in a context of price stability.[197]

- June 17, 2009: Barack Obama and key advisers introduced a series of regulatory proposals that addressed consumer protection, executive pay, bank capital requirements, expanded regulation of the shadow banking system and derivatives, and enhanced authority for the Federal Reserve to safely wind down systemically important institutions.[198][199][200]

- December 11, 2009: United States House of Representatives passed bill H.R. 4173, a precursor to what became the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act.[201]

2010

- January 22, 2010: President Obama introduced "The Volcker Rule" limiting the ability of banks to engage in proprietary trading, named after Paul Volcker, who publicly argued for the proposed changes.[202][203] Obama also proposed a Financial Crisis Responsibility Fee on large banks.

- January 27, 2010: President Obama declared on "the markets are now stabilized, and we've recovered most of the money we spent on the banks".[204]

- First quarter 2010: Delinquency rates in the United States peaked at 11.54%.[205]

- April 15, 2010: U.S. Senate introduced bill S.3217, Restoring American Financial Stability Act of 2010.[206]

- May 2010: The U.S. Senate passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. The Volcker Rule against proprietary trading was not part of the legislation.[207]

- July 21, 2010: Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act enacted.[208][209]

- September 12, 2010: European regulators introduced Basel III regulations for banks, which increased capital ratios, limits on leverage, narrowed the definition of capital to exclude subordinated debt, limited counter-party risk, and added liquidity requirements.[210][211] Critics argued that Basel III didn't address the problem of faulty risk-weightings. Major banks suffered losses from AAA-rated created by financial engineering (which creates apparently risk-free assets out of high risk collateral) that required less capital according to Basel II. Lending to AA-rated sovereigns has a risk-weight of zero, thus increasing lending to governments and leading to the next crisis.[212] Johan Norberg argued that regulations (Basel III among others) have indeed led to excessive lending to risky governments (see European sovereign-debt crisis) and the European Central Bank pursues even more lending as the solution.[213]

- November 3, 2010: To improve economic growth, the Federal Reserve announced another round of quantitative easing, dubbed QE2, which included the purchase of $600 billion in long-term Treasuries over the following eight months.[214]

Post-2010

- March 2011: Two years after the nadir of the crisis, many stock market indices were 75% above their lows set in March 2009. Nevertheless, the lack of fundamental changes in banking and financial markets worried many market participants, including the International Monetary Fund.[215]

- 2011: Median household wealth fell 35% in the U.S., from $106,591 to $68,839 between 2005 and 2011.[216]

- May 2012: The Manhattan District Attorney indicted Abacus Federal Savings Bank and 19 employees for selling fraudulent mortgages to Fannie Mae. The bank was acquitted in 2015. Abacus was the only bank prosecuted for misbehavior that precipitated the crisis.

- July 26, 2012: During the European debt crisis, President of the European Central Bank Mario Draghi announced that "The ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro".[217]

- August 2012: In the United States, many homeowners still faced foreclosure and could not refinance or modify their mortgages. Foreclosure rates remained high.[218]

- September 13, 2012: To improve lower interest rates, support mortgage markets, and make financial conditions more accommodative, the Federal Reserve announced another round of quantitative easing, dubbed QE3, which included the purchase of $40 billion in long-term Treasuries each month.[219]

- 2014: A report showed that the distribution of household incomes in the United States became more unequal during the post-2008 economic recovery, a first for the United States but in line with the trend over the last ten economic recoveries since 1949.[220][221] Income inequality in the United States grew from 2005 to 2012 in more than 2 out of 3 metropolitan areas.[222]

- June 2015: A study commissioned by the ACLU found that white home-owning households recovered from the financial crisis faster than black home-owning households, widening the racial wealth gap in the U.S.[223]

- 2017: Per the International Monetary Fund, from 2007 to 2017, "advanced" economies accounted for only 26.5% of global GDP (PPP) growth while emerging and developing economies accounted for 73.5% of global GDP (PPP) growth.[224]

- August 2023: UBS reaches an agreement with the United States Department of Justice to pay a combined $1.435 billion in civil penalties to settle a legacy matter from 2006–2007 related to the issuance, underwriting and sale of residential mortgage-backed securities.[225]

In the table, the names of emerging and developing economies are shown in boldface type, while the names of developed economies are in Roman (regular) type.

| Economy | Incremental GDP (billions in USD)

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (01) |

14,147

| ||||||||

| (02) |

5,348

| ||||||||

| (03) |

4,913

| ||||||||

| (—) |

4,457

| ||||||||

| (04) |

1,632

| ||||||||

| (05) |

1,024

| ||||||||

| (06) |

1,003

| ||||||||

| (07) |

984

| ||||||||

| (08) |

934

| ||||||||

| (09) |

919

| ||||||||

| (10) |

744

| ||||||||

| (11) |

733

| ||||||||

| (12) |

700

| ||||||||

| (13) |

671

| ||||||||

| (14) |

566

| ||||||||

| (15) |

523

| ||||||||

| (16) |

505

| ||||||||

| (17) |

482

| ||||||||

| (18) |

462

| ||||||||

| (19) |

447

| ||||||||

| (20) |

440

| ||||||||

|

The twenty largest economies contributing to global GDP (PPP) growth (2007–2017)[226] | |||||||||

Fed's action towards crisis

The expansion of central bank lending in response to the crisis was not only confined to the Federal Reserve's provision of aid to individual financial institutions. The Federal Reserve has also conducted a number of innovative lending programs with the goal of improving liquidity and strengthening different financial institutions and markets, such as Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae. In this case, the major problem among the market is the lack of free cash reserves and flows to secure the loans. The Federal Reserve took a number of steps to deal with worries about liquidity in the financial markets. One of these steps was a credit line for major traders, who act as the Fed's partners in open market activities.[227] Also, loan programs were set up to make the money market mutual funds and commercial paper market more flexible. Also, the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) was put in place thanks to a joint effort with the US Department of the Treasury. This plan was meant to make it easier for consumers and businesses to get credit by giving Americans who owned high-quality asset-backed securities more credit.

Before the crisis, the Federal Reserve's stocks of Treasury securities were sold to pay for the increase in credit. This method was meant to keep banks from trying to give out their extra savings, which could cause the federal funds rate to drop below where it was supposed to be.[228] However, in October 2008, the Federal Reserve was granted the power to provide banks with interest payments on their surplus reserves. This created a motivation for banks to retain their reserves instead of disbursing them, so reducing the need for the Federal Reserve to hedge its increased lending by decreases in alternative assets.[229]

Money market funds also went through runs when people lost faith in the market. To keep it from getting worse, the Fed said it would give money to mutual fund companies. Also, Department of Treasury said that it would briefly cover the assets of the fund. Both of these things helped get the fund market back to normal, which helped the commercial paper market, which most businesses use to run. The FDIC also did a number of things, like raise the insurance cap from $100,000 to $250,000, to boost customer trust.

They engaged in Quantitative Easing, which added more than $4 trillion to the financial system and got banks to start lending again, both to each other and to people. Many homeowners who were trying to keep their homes from going into default got housing credits. A package of policies was passed that let borrowers refinance their loans even though the value of their homes was less than what they still owed on their mortgages.[230]

Causes

While the causes of the bubble and subsequent crash are disputed, the precipitating factor for the Financial Crisis of 2007–2008 was the bursting of the United States housing bubble and the subsequent subprime mortgage crisis, which occurred due to a high default rate and resulting foreclosures of mortgage loans, particularly adjustable-rate mortgages. Some or all of the following factors contributed to the crisis:[231][88][89]

- In its January 2011 report, the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC, a committee of U.S. congressmen) concluded that the financial crisis was avoidable and was caused by:[232][233][234][235][236]

- "widespread failures in financial regulation and supervision", including the Federal Reserve's failure to stem the tide of toxic assets.

- "dramatic failures of corporate governance and risk management at many systemically important financial institutions" including too many financial firms acting recklessly and taking on too much risk.

- "a combination of excessive borrowing, risky investments, and lack of transparency" by financial institutions and by households that put the financial system on a collision course with crisis.

- ill preparation and inconsistent action by government and key policy makers lacking a full understanding of the financial system they oversaw that "added to the uncertainty and panic".

- a "systemic breakdown in accountability and ethics" at all levels.

- "collapsing mortgage-lending standards and the mortgage securitization pipeline".

- deregulation of 'over-the-counter' derivatives, especially credit default swaps.

- "the failures of credit rating agencies" to correctly price risk.

- "Wall Street and the Financial Crisis: Anatomy of a Financial Collapse" (known as the Levin–Coburn Report) by the United States Senate concluded that the crisis was the result of "high risk, complex financial products; undisclosed conflicts of interest; the failure of regulators, the credit rating agencies, and the market itself to rein in the excesses of Wall Street".[237]

- The high delinquency and default rates by homeowners, particularly those with subprime credit, led to a rapid devaluation of mortgage-backed securities including bundled loan portfolios, derivatives and credit default swaps. As the value of these assets plummeted, buyers for these securities evaporated and banks who were heavily invested in these assets began to experience a liquidity crisis.

- Securitization, a process in which many mortgages were bundled together and formed into new financial instruments called mortgage-backed securities, allowed for shifting of risk and lax underwriting standards. These bundles could be sold as (ostensibly) low-risk securities partly because they were often backed by credit default swap insurance.[238] Because mortgage lenders could pass these mortgages (and the associated risks) on in this way, they could and did adopt loose underwriting criteria.

- Lax regulation allowed predatory lending in the private sector,[239][240] especially after the federal government overrode anti-predatory state laws in 2004.[241]

- The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA),[242] a 1977 U.S. federal law designed to help low- and moderate-income Americans get mortgage loans required banks to grant mortgages to higher risk families.[243][244][245][246] Granted, in 2009, Federal Reserve economists found that, "only a small portion of subprime mortgage originations to the CRA", and that "CRA-related loans appear to perform comparably to other types of subprime loans". These findings "run counter to the contention that the CRA contributed in any substantive way to the ."[247]

- Reckless lending by lenders such as Bank of America's Countrywide Financial unit was increasingly incentivized and even mandated by government regulation.[248][249][250] This may have caused Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to lose market share and to respond by lowering their own standards.[251]

- Mortgage guarantees by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, quasi-government agencies, which purchased many subprime loan securitizations.[252] The implicit guarantee by the U.S. federal government created a moral hazard and contributed to a glut of risky lending.

- Government policies that encouraged home ownership, providing easier access to loans for subprime borrowers; overvaluation of bundled subprime mortgages based on the theory that housing prices would continue to escalate; questionable trading practices on behalf of both buyers and sellers; compensation structures by banks and mortgage originators that prioritize short-term deal flow over long-term value creation; and a lack of adequate capital holdings from banks and insurance companies to back the financial commitments they were making.[253][254]

- The 1999 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, which partially repealed the Glass-Steagall Act, effectively removed the separation between investment banks and depository banks in the United States and increased speculation on the part of depository banks.[255]

- Credit rating agencies and investors failed to accurately price the financial risk involved with mortgage loan-related financial products, and governments did not adjust their regulatory practices to address changes in financial markets.[256][257][258]

- Variations in the cost of borrowing.[259]

- Fair value accounting was issued as U.S. accounting standard SFAS 157 in 2006 by the privately run Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB)—delegated by the SEC with the task of establishing financial reporting standards.[260] This required that tradable assets such as mortgage securities be valued according to their current market value rather than their historic cost or some future expected value. When the market for such securities became volatile and collapsed, the resulting loss of value had a major financial effect upon the institutions holding them even if they had no immediate plans to sell them.[261]

- Easy availability of credit in the US, fueled by large inflows of foreign funds after the 1998 Russian financial crisis and 1997 Asian financial crisis of the 1997–1998 period, led to a housing construction boom and facilitated debt-financed consumer spending. As banks began to give out more loans to potential home owners, housing prices began to rise. Lax lending standards and rising real estate prices also contributed to the real estate bubble. Loans of various types (e.g., mortgage, credit card, and auto) were easy to obtain and consumers assumed an unprecedented debt load.[262][231][263]

- As part of the housing and credit booms, the number of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDO), which derived their value from mortgage payments and housing prices, greatly increased. Such financial innovation enabled institutions and investors to invest in the U.S. housing market. As housing prices declined, these investors reported significant losses.[264]

- Falling prices also resulted in homes worth less than the mortgage loans, providing borrowers with a financial incentive to enter foreclosure. Foreclosure levels were elevated until early 2014.[265] drained significant wealth from consumers, losing up to $4.2 trillion[266] Defaults and losses on other loan types also increased significantly as the crisis expanded from the housing market to other parts of the economy. Total losses were estimated in the trillions of U.S. dollars globally.[264]

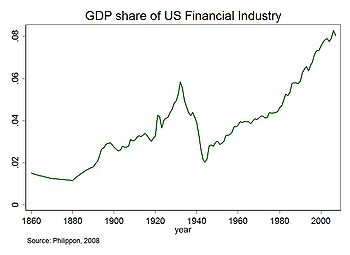

- Financialization – the increased use of leverage in the financial system.

- Financial institutions such as investment banks and hedge funds, as well as certain, differently regulated banks, assumed significant debt burdens while providing the loans described above and did not have a financial cushion sufficient to absorb large loan defaults or losses.[267] These losses affected the ability of financial institutions to lend, slowing economic activity.

- Some critics contend that government mandates forced banks to extend loans to borrowers previously considered uncreditworthy, leading to increasingly lax underwriting standards and high mortgage approval rates.[268][248][269][249] These, in turn, led to an increase in the number of homebuyers, which drove up housing prices. This appreciation in value led many homeowners to borrow against the equity in their homes as an apparent windfall, leading to over-leveraging.

Subprime lending

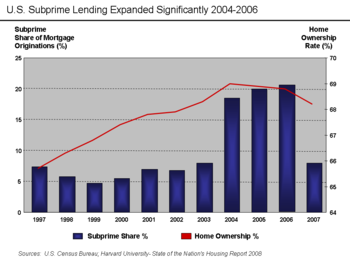

The relaxing of credit lending standards by investment banks and commercial banks allowed for a significant increase in subprime lending. Subprime had not become less risky; Wall Street just accepted this higher risk.[270]

Due to competition between mortgage lenders for revenue and market share, and when the supply of creditworthy borrowers was limited, mortgage lenders relaxed underwriting standards and originated riskier mortgages to less creditworthy borrowers. In the view of some analysts, the relatively conservative government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) policed mortgage originators and maintained relatively high underwriting standards prior to 2003. However, as market power shifted from securitizers to originators, and as intense competition from private securitizers undermined GSE power, mortgage standards declined and risky loans proliferated. The riskiest loans were originated in 2004–2007, the years of the most intense competition between securitizers and the lowest market share for the GSEs. The GSEs eventually relaxed their standards to try to catch up with the private banks.[271][272]

A contrarian view is that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac led the way to relaxed underwriting standards, starting in 1995, by advocating the use of easy-to-qualify automated underwriting and appraisal systems, by designing no-down-payment products issued by lenders, by the promotion of thousands of small mortgage brokers, and by their close relationship to subprime loan aggregators such as Countrywide.[273][274]

Depending on how "subprime" mortgages are defined, they remained below 10% of all mortgage originations until 2004, when they rose to nearly 20% and remained there through the 2005–2006 peak of the United States housing bubble.[275]

Role of affordable housing programs

The majority report of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, written by the six Democratic appointees, the minority report, written by three of the four Republican appointees, studies by Federal Reserve economists, and the work of several independent scholars generally contend that government affordable housing policy was not the primary cause of the financial crisis. Although they concede that governmental policies had some role in causing the crisis, they contend that GSE loans performed better than loans securitized by private investment banks, and performed better than some loans originated by institutions that held loans in their own portfolios.

In his dissent to the majority report of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, conservative American Enterprise Institute fellow Peter J. Wallison[276] stated his belief that the roots of the financial crisis can be traced directly and primarily to affordable housing policies initiated by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in the 1990s and to massive risky loan purchases by government-sponsored entities Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Based upon information in the SEC's December 2011 securities fraud case against six former executives of Fannie and Freddie, Peter Wallison and Edward Pinto estimated that, in 2008, Fannie and Freddie held 13 million substandard loans totaling over $2 trillion.[277]

In the early and mid-2000s, the Bush administration called numerous times for investigations into the safety and soundness of the GSEs and their swelling portfolio of subprime mortgages. On September 10, 2003, the United States House Committee on Financial Services held a hearing, at the urging of the administration, to assess safety and soundness issues and to review a recent report by the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight (OFHEO) that had uncovered accounting discrepancies within the two entities.[278][279] The hearings never resulted in new legislation or formal investigation of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, as many of the committee members refused to accept the report and instead rebuked OFHEO for their attempt at regulation.[280] Some, such as Wallison, believe this was an early warning to the systemic risk that the growing market in subprime mortgages posed to the U.S. financial system that went unheeded.[281]

A 2000 United States Department of the Treasury study of lending trends for 305 cities from 1993 to 1998 showed that $467 billion of mortgage lending was made by Community Reinvestment Act (CRA)-covered lenders into low and mid-level income (LMI) borrowers and neighborhoods, representing 10% of all U.S. mortgage lending during the period. The majority of these were prime loans. Sub-prime loans made by CRA-covered institutions constituted a 3% market share of LMI loans in 1998,[282] but in the run-up to the crisis, fully 25% of all subprime lending occurred at CRA-covered institutions and another 25% of subprime loans had some connection with CRA.[283] However, most sub-prime loans were not made to the LMI borrowers targeted by the CRA,[citation needed][284][285] especially in the years 2005–2006 leading up to the crisis,[citation needed][286][285][287] nor did it find any evidence that lending under the CRA rules increased delinquency rates or that the CRA indirectly influenced independent mortgage lenders to ramp up sub-prime lending.[288][verification needed]

To other analysts the delay between CRA rule changes in 1995 and the explosion of subprime lending is not surprising, and does not exonerate the CRA. They contend that there were two, connected causes to the crisis: the relaxation of underwriting standards in 1995 and the ultra-low interest rates initiated by the Federal Reserve after the terrorist attack on September 11, 2001. Both causes had to be in place before the crisis could take place.[289] Critics also point out that publicly announced CRA loan commitments were massive, totaling $4.5 trillion in the years between 1994 and 2007.[290] They also argue that the Federal Reserve's classification of CRA loans as "prime" is based on the faulty and self-serving assumption that high-interest-rate loans (3 percentage points over average) equal "subprime" loans.[291]

Others have pointed out that there were not enough of these loans made to cause a crisis of this magnitude. In an article in Portfolio magazine, Michael Lewis spoke with one trader who noted that "There weren't enough Americans with credit taking out to satisfy investors' appetite for the end product." Essentially, investment banks and hedge funds used financial innovation to enable large wagers to be made, far beyond the actual value of the underlying mortgage loans, using derivatives called credit default swaps, collateralized debt obligations and synthetic CDOs.

By March 2011, the FDIC had paid out $9 billion (c. $12 billion in 2023[292]) to cover losses on bad loans at 165 failed financial institutions.[293][294] The Congressional Budget Office estimated, in June 2011, that the bailout to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac exceeds $300 billion (c. $401 billion in 2023[292]) (calculated by adding the fair value deficits of the entities to the direct bailout funds at the time).[295]

Economist Paul Krugman argued in January 2010 that the simultaneous growth of the residential and commercial real estate pricing bubbles and the global nature of the crisis undermines the case made by those who argue that Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, CRA, or predatory lending were primary causes of the crisis. In other words, bubbles in both markets developed even though only the residential market was affected by these potential causes.[296]

Countering Krugman, Wallison wrote: "It is not true that every bubble—even a large bubble—has the potential to cause a financial crisis when it deflates." Wallison notes that other developed countries had "large bubbles during the 1997–2007 period" but "the losses associated with mortgage delinquencies and defaults when these bubbles deflated were far lower than the losses suffered in the United States when the 1997–2007 deflated." According to Wallison, the reason the U.S. residential housing bubble (as opposed to other types of bubbles) led to financial crisis was that it was supported by a huge number of substandard loans—generally with low or no downpayments.[297]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Financial_crisis_of_2007-08

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk