A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Deinonychus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton cast, Field Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Dromaeosauridae |

| Clade: | †Eudromaeosauria |

| Genus: | †Deinonychus Ostrom, 1969 |

| Type species | |

| †Deinonychus antirrhopus Ostrom, 1969

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Deinonychus (/daɪˈnɒnɪkəs/[1] dy-NON-ih-kəs; from Ancient Greek δεινός (deinós) 'terrible', and ὄνυξ (ónux), genitive ὄνυχος (ónukhos) 'claw') is a genus of dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaur with one described species, Deinonychus antirrhopus. This species, which could grow up to 3.4 meters (11 ft) long, lived during the early Cretaceous Period, about 115–108 million years ago (from the mid-Aptian to early Albian stages). Fossils have been recovered from the U.S. states of Montana, Utah, Wyoming, and Oklahoma, in rocks of the Cloverly Formation and Antlers Formation, though teeth that may belong to Deinonychus have been found much farther east in Maryland.

Paleontologist John Ostrom's study of Deinonychus in the late 1960s revolutionized the way scientists thought about dinosaurs, leading to the "dinosaur renaissance" and igniting the debate on whether dinosaurs were warm-blooded or cold-blooded. Before this, the popular conception of dinosaurs had been one of plodding, reptilian giants. Ostrom noted the small body, sleek, horizontal posture, ratite-like spine, and especially the enlarged raptorial claws on the feet, which suggested an active, agile predator.[2]

"Terrible claw" refers to the unusually large, sickle-shaped talon on the second toe of each hind foot. The fossil YPM 5205 preserves a large, strongly curved ungual. In life, archosaurs have a horny sheath over this bone, which extends the length. Ostrom looked at crocodile and bird claws and reconstructed the claw for YPM 5205 as over 120 millimetres (4.7 in) long.[2] The species name antirrhopus means "counter balance", which refers to Ostrom's idea about the function of the tail. As in other dromaeosaurids, the tail vertebrae have a series of ossified tendons and super-elongated bone processes. These features seemed to make the tail into a stiff counterbalance, but a fossil of the very closely related Velociraptor mongoliensis (IGM 100/986) has an articulated tail skeleton that is curved laterally in a long S-shape. This suggests that, in life, the tail could bend to the sides with a high degree of flexibility.[3] In both the Cloverly and Antlers formations, Deinonychus remains have been found closely associated with those of the ornithopod Tenontosaurus. Teeth discovered associated with Tenontosaurus specimens imply they were hunted, or at least scavenged upon, by Deinonychus.

Discovery and naming

Fossilized remains of Deinonychus have been recovered from the Cloverly Formation of Montana and Wyoming[2] and in the roughly contemporary Antlers Formation of Oklahoma,[4] in North America. The Cloverly formation has been dated to the late Aptian through early Albian stages of the early Cretaceous, about 115 to 108 Ma.[5][6] Additionally, teeth found in the Arundel Clay Facies (mid-Aptian), of the Potomac Formation on the Atlantic Coastal Plain of Maryland may be assigned to the genus.[7]

The first remains were uncovered in 1931 in southern Montana near the town of Billings. The team leader, paleontologist Barnum Brown, was primarily concerned with excavating and preparing the remains of the ornithopod dinosaur Tenontosaurus, but in his field report from the dig site to the American Museum of Natural History, he reported the discovery of a small carnivorous dinosaur close to a Tenontosaurus skeleton, "but encased in lime difficult to prepare."[8] He informally called the animal "Daptosaurus agilis" and made preparations for describing it and having the skeleton, specimen AMNH 3015, put on display, but never finished this work.[9] Brown brought back from the Cloverly Formation the skeleton of a smaller theropod with seemingly oversized teeth that he informally named "Megadontosaurus". John Ostrom, reviewing this material decades later, realized that the teeth came from Deinonychus, but the skeleton came from a completely different animal. He named this skeleton Microvenator.[9]

A little more than thirty years later, in August 1964, paleontologist John Ostrom led an expedition from Yale's Peabody Museum of Natural History which discovered more skeletal material near Bridger. Expeditions during the following two summers uncovered more than 1,000 bones, among which were at least three individuals. Since the association between the various recovered bones was weak, making the exact number of individual animals represented impossible to determine properly, the type specimen (YPM 5205) of Deinonychus was restricted to the complete left foot and partial right foot that definitely belonged to the same individual.[10] The remaining specimens were catalogued in fifty separate entries at Yale's Peabody Museum although they could have been from as few as three individuals.[10]

Later study by Ostrom and Grant E. Meyer analyzed their own material as well as Brown's "Daptosaurus" in detail and found them to be the same species. Ostrom first published his findings in February 1969, giving all the referred remains the new name of Deinonychus antirrhopus. The specific name "antirrhopus", from Greek ἀντίρροπος, means "counterbalancing" and refers to the likely purpose of a stiffened tail.[11] In July 1969, Ostrom published a very extensive monograph on Deinonychus.[10]

Though a myriad of bones was available by 1969, many important ones were missing or hard to interpret. There were few postorbital skull elements, no femurs, no sacrum, no furcula or sternum, missing vertebrae, and (Ostrom thought) only a tiny fragment of a coracoid. Ostrom's skeletal reconstruction of Deinonychus included a very unusual pelvic bone—a pubis that was trapezoidal and flat, unlike that of other theropods, but which was the same length as the ischium and which was found right next to it.[10]

Further findings

In 1974, Ostrom published another monograph on the shoulder of Deinonychus in which he realized that the pubis that he had described was actually a coracoid—a shoulder element.[12] In that same year, another specimen of Deinonychus, MCZ 4371, was discovered and excavated in Montana by Steven Orzack during a Harvard University expedition headed by Farish Jenkins. This discovery added several new elements: well preserved femora, pubes, a sacrum, and better ilia, as well as elements of the pes and metatarsus. Ostrom described this specimen and revised his skeletal restoration of Deinonychus. This time it showed the very long pubis, and Ostrom began to suspect that they may have even been a little retroverted like those of birds.[13]

A skeleton of Deinonychus, including bones from the original (and most complete) AMNH 3015 specimen, can be seen on display at the American Museum of Natural History,[14] with another specimen (MCZ 4371) on display at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University. The American Museum and Harvard specimens are from a different locality than the Yale specimens. Even these two skeletal mounts are lacking elements, including the sterna, sternal ribs, furcula, and gastralia.[15]

Even after all Ostrom's work, several small blocks of lime-encased material remained unprepared in storage at the American Museum. These consisted mostly of isolated bones and bone fragments, including the original matrix, or surrounding rock in which the specimens were initially buried. An examination of these unprepared blocks by Gerald Grellet-Tinner and Peter Makovicky in 2000 revealed an interesting, overlooked feature. Several long, thin bones identified on the blocks as ossified tendons (structures that helped stiffen the tail of Deinonychus) turned out to actually represent gastralia (abdominal ribs). More significantly, a large number of previously unnoticed fossilized eggshells were discovered in the rock matrix that had surrounded the original Deinonychus specimen.[16]

In a subsequent, more detailed report, on the eggshells, Grellet-Tinner and Makovicky concluded that the egg almost certainly belonged to Deinonychus, representing the first dromaeosaurid egg to be identified.[8] Moreover, the external surface of one eggshell was found in close contact with the gastralia suggesting that Deinonychus might have brooded its eggs. This implies that Deinonychus used body heat transfer as a mechanism for egg incubation, and indicates an endothermy similar to modern birds.[17] Further study by Gregory Erickson and colleagues finds that this individual was 13 or 14 years old at death and its growth had plateaued. Unlike other theropods in their study of specimens found associated with eggs or nests, it had finished growing at the time of its death.[18]

Implications

Ostrom's description of Deinonychus in 1969 has been described as the most important single discovery of dinosaur paleontology in the mid-20th century.[19] The discovery of this clearly active, agile predator did much to change the scientific (and popular) conception of dinosaurs and opened the door to speculation that some dinosaurs may have been warm-blooded. This development has been termed the dinosaur renaissance. Several years later, Ostrom noted similarities between the forefeet of Deinonychus and that of birds, an observation which led him to revive the hypothesis that birds are descended from dinosaurs.[20] Forty years later, this idea is almost universally accepted.

Because of its extremely bird-like anatomy and close relationship to other dromaeosaurids, paleontologists hypothesize that Deinonychus was probably covered in feathers.[21][22][23] Clear fossil evidence of modern avian-style feathers exists for several related dromaeosaurids, including Velociraptor and Microraptor, though no direct evidence is yet known for Deinonychus itself.[24][25] When conducting studies of such areas as the range of motion in the forelimbs, paleontologists like Phil Senter have taken the likely presence of wing feathers (as present in all known dromaeosaurs with skin impressions) into consideration.[26]

Description

Based on the few fully mature specimens,[27] Paul estimated that Deinonychus could reach 3.3–3.4 meters (10 ft 10 in – 11 ft 2 in) in length, with a skull length of 410 millimeters (16 in), a hip height of 0.87 meters (2.9 ft) and a body mass of 60–73 kg (132–161 lb).[28][29] Campione and his colleagues proposed a higher mass estimate of 100 kg (220 lb) based on femur and humerus circumference.[30] The skull was equipped with powerful jaws lined with around seventy curved, blade-like teeth. Studies of the skull have progressed a great deal over the decades. Ostrom reconstructed the partial, imperfectly preserved skulls that he had as triangular, broad, and fairly similar to Allosaurus. Additional Deinonychus skull material and closely related species found with good three-dimensional preservation[31] show that the palate was more vaulted than Ostrom thought, making the snout far narrower, while the jugals flared broadly, giving greater stereoscopic vision. The skull of Deinonychus was different from that of Velociraptor, however, in that it had a more robust skull roof, like that of Dromaeosaurus, and did not have the depressed nasals of Velociraptor.[32] Both the skull and the lower jaw had fenestrae (skull openings) which reduced the weight of the skull. In Deinonychus, the antorbital fenestra, a skull opening between the eye and nostril, was particularly large.[31]

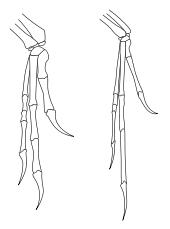

Deinonychus possessed large "hands" (manus) with three claws on each forelimb. The first digit was shortest and the second was longest. Each hind foot bore a sickle-shaped claw on the second digit, which was probably used during predation.[10]

No skin impressions have ever been found in association with fossils of Deinonychus. Nonetheless, the evidence suggests that the Dromaeosauridae, including Deinonychus, had feathers.[24] The genus Microraptor is both older geologically and more primitive phylogenetically than Deinonychus, and within the same family.[33] Multiple fossils of Microraptor preserve pennaceous, vaned feathers like those of modern birds on the arms, legs, and tail, along with covert and contour feathers.[24] Velociraptor is geologically younger than Deinonychus, but even more closely related. A specimen of Velociraptor has been found with quill knobs on the ulna. Quill knobs are where the follicular ligaments attached, and are a direct indicator of feathers of modern aspect.[25]

Classification

Deinonychus antirrhopus is one of the best known dromaeosaurid species,[34] and also a close relative of the smaller Velociraptor, which is found in younger, Late Cretaceous-age rock formations in Central Asia.[35][36] The clade they form is called Velociraptorinae. The subfamily name Velociraptorinae was first coined by Rinchen Barsbold in 1983[37] and originally contained the single genus Velociraptor. Later, Phil Currie included most of the dromaeosaurids.[38] Two Late Cretaceous genera, Tsaagan from Mongolia[35] and the North American Saurornitholestes,[28] may also be close relatives, but the latter is poorly known and hard to classify.[35] Velociraptor and its allies are regarded as using their claws more than their skulls as killing tools, as opposed to dromaeosaurines like Dromaeosaurus, which have stockier skulls.[28] Phylogenetically, the dromaeosaurids represent one of the non-avialan dinosaur groups most closely related to birds.[39] The cladogram below follows a 2015 analysis by paleontologists Robert DePalma, David Burnham, Larry Martin, Peter Larson, and Robert Bakker, using updated data from the Theropod Working Group. This study currently classifies Deinonychus as a member of the Dromaeosaurinae.[40]

A 2021 study of the dromaeosaurid Kansaignathus recovered Deinonychus as a velociraptorine rather than a dromaeosaurine, with Kansaignathus being an intermediate basal form more advanced than Deinonychus but more primitive than Velociraptor.[41][42] The cladogram below showcases these newly described relationships: