A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Potato | |

|---|---|

| |

| Potato cultivars appear in a variety of colors, shapes, and sizes. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Solanales |

| Family: | Solanaceae |

| Genus: | Solanum |

| Species: | S. tuberosum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Solanum tuberosum | |

| Synonyms | |

|

see list | |

The potato (/pəˈteɪtoʊ/) is a starchy root vegetable native to the Americas that is consumed as a staple food in many parts of the world. Potatoes are tubers of the plant Solanum tuberosum, a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern United States to southern Chile. Genetic studies show that the cultivated potato has a single origin, in the area of present-day southern Peru and extreme northwestern Bolivia. Potatoes were domesticated there about 7,000–10,000 years ago from a species in the S. brevicaule complex. Many varieties of the potato are cultivated in the Andes region of South America, where the species is indigenous.

The Spanish introduced potatoes to Europe in the second half of the 16th century from the Americas. They are a staple food in many parts of the world and an integral part of much of the world's food supply. Following millennia of selective breeding, there are now over 5,000 different varieties of potatoes. The potato remains an essential crop in Europe, especially Northern and Eastern Europe, where per capita production is still the highest in the world, while the most rapid expansion in production during the 21st century was in southern and eastern Asia, with China and India leading the world production as of 2021.

Like the tomato and the nightshades, the potato is in the genus Solanum; the aerial parts of the potato contain the toxin solanine. Normal potato tubers that have been grown and stored properly produce glycoalkaloids in negligible amounts, but, if sprouts and potato skins are exposed to light, tubers can become toxic.

Etymology

The English word "potato" comes from Spanish patata, in turn from Taíno batata, which means "sweet potato", not the plant now known as simply "potato".[1]

The name "spud" for a potato is from the 15th century spudde, a short knife or dagger, probably related to Danish spyd, "spear". From around 1840, the name transferred to the tuber itself.[2]

At least six languages—Afrikaans, Dutch, French, (West) Frisian, Hebrew, Persian[3] and some variants of German—use a term for "potato" that means "earth apple" or "ground apple".[4][5]

Description

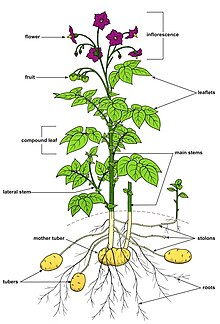

Potato plants are herbaceous perennials that grow up to 1 metre (3.3 ft) high. The stems are hairy. The leaves have roughly four pairs of leaflets. The flowers range from white or pink to blue or purple; they are yellow at the centre, and are insect-pollinated.[6]

The plant develops tubers, the potatoes of commerce, to store nutrients. These are not roots but stems that form from thickened rhizomes at the tips of long thin stolons. On the surface of the tubers there are "eyes," which act as sinks to protect the vegetative buds from which the stems originate. The "eyes" are arranged in helical form. In addition, the tubers have small holes that allow breathing, called lenticels. The lenticels are circular and their number varies depending on the size of the tuber and environmental conditions.[7] Tubers form in response to decreasing day length, although this tendency has been minimized in commercial varieties.[8]

After flowering, potato plants produce small green fruits that resemble green cherry tomatoes, each containing about 300 very small seeds.[9]

Phylogeny

Wild and cultivated potatoes, like the tomato, belong to the genus Solanum, which is a member of the nightshade family, the Solanaceae. That is a diverse family of flowering plants, often poisonous, that includes the mandrake (Mandragora), deadly nightshade (Atropa), and tobacco (Nicotiana), as shown in the outline phylogenetic tree (many branches omitted). The most commonly cultivated potato is S. tuberosum; there are several other species.[10]

| Solanaceae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The major species grown worldwide is S. tuberosum (a tetraploid with 48 chromosomes), and modern varieties of this species are the most widely cultivated. There are also four diploid species (with 24 chromosomes): S. stenotomum, S. phureja, S. goniocalyx, and S. ajanhuiri. There are two triploid species (with 36 chromosomes): S. chaucha and S. juzepczukii. There is one pentaploid cultivated species (with 60 chromosomes): S. curtilobum.[11]

There are two major subspecies of S. tuberosum.[11] The Andean potato, S. tuberosum andigena, is adapted to the short-day conditions prevalent in the mountainous equatorial and tropical regions where it originated. The Chilean potato S. tuberosum tuberosum, native to the Chiloé Archipelago, is in contrast adapted to the long-day conditions prevalent in the higher latitude region of southern Chile.[12]

History

Domestication

Wild potato species occur from the southern United States to southern Chile.[13] The potato was first domesticated in southern Peru and northwestern Bolivia[14] by pre-Columbian farmers, around Lake Titicaca.[15] Potatoes were domesticated there about 7,000–10,000 years ago from a species in the S. brevicaule complex.[14][15][16]

The earliest archaeologically verified potato tuber remains have been found at the coastal site of Ancon (central Peru), dating to 2500 BC.[17][18] The most widely cultivated variety, Solanum tuberosum tuberosum, is indigenous to the Chiloé Archipelago, and has been cultivated by the local indigenous people since before the Spanish conquest.[12][19]

Spread

Following the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, the Spanish introduced the potato to Europe in the second half of the 16th century as part of the Columbian exchange. The staple was subsequently conveyed by European mariners (possibly including the Russian-American Company) to territories and ports throughout the world, especially their colonies.[20] European and colonial farmers were slow to adopt farming potatoes, but after 1750 they became an important food staple and field crop[20] and played a major role in the European 19th century population boom.[16] According to conservative estimates, the introduction of the potato was responsible for a quarter of the growth in Old World population and urbanization between 1700 and 1900.[21] However, lack of genetic diversity, due to the very limited number of varieties initially introduced, left the crop vulnerable to disease. In 1845, a plant disease known as late blight, caused by the fungus-like oomycete Phytophthora infestans, spread rapidly through the poorer communities of western Ireland as well as parts of the Scottish Highlands, resulting in the crop failures that led to the Great Irish Famine.[22][20]

The International Potato Center, based in Lima, Peru, holds 4,870 types of potato germplasm, most of which are traditional landrace cultivars.[23] In 2009 a draft sequence of the potato genome was made, containing 12 chromosomes and 860 million base pairs, making it a medium-sized plant genome.[24]

It had been thought that most potato cultivars derived from a single origin in southern Peru and extreme Northwestern Bolivia, from a species in the S. brevicaule complex.[14][15][16] DNA analysis however shows that more than 99% of all current varieties of potatoes are direct descendants of a subspecies that once grew in the lowlands of south-central Chile.[25]

Most modern potatoes grown in North America arrived through European settlement and not independently from the South American sources. At least one wild potato species, S. fendleri, occurs in North America; it is used in breeding for resistance to a nematode species that attacks cultivated potatoes. A secondary center of genetic variability of the potato is Mexico, where important wild species that have been used extensively in modern breeding are found, such as the hexaploid S. demissum, used as a source of resistance to the devastating late blight disease (Phytophthora infestans).[22] Another relative native to this region, Solanum bulbocastanum, has been used to genetically engineer the potato to resist potato blight.[26] Many such wild relatives are useful for breeding resistance to P. infestans.[27]

Little of the diversity found in Solanum ancestral and wild relatives is found outside the original South American range.[28] This makes these South American species highly valuable in breeding.[28] The importance of the potato to humanity is recognised in the United Nations International Day of Potato, to be celebrated on 30 May each year, starting in 2024.[29]

Breeding

Potatoes, both S. tuberosum and most of its wild relatives, are self-incompatible: they bear no useful fruit when self-pollinated. This trait is problematic for crop breeding, as all sexually-produced plants must be hybrids. The gene responsible for self-incompatibility, as well as mutations to disable it, are now known. Self-compatibility has successfully been introduced both to diploid potatoes (including a special line of S. tuberosum) by CRISPR-Cas9.[30] Plants having a 'Sli' gene produce pollen which is compatible to its own parent and plants with similar S genes.[31] This gene was cloned by Wageningen University and Solynta in 2021, which would allow for faster and more focused breeding.[30][32]

Diploid hybrid potato breeding is a recent area of potato genetics supported by the finding that simultaneous homozygosity and fixation of donor alleles is possible.[33] Wild potato species useful for breeding blight resistance include Solanum desmissum and S. stoloniferum, among others.[34]

Varieties

There are some 5,000 potato varieties worldwide, 3,000 of them in the Andes alone — mainly in Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile, and Colombia. Over 100 cultivars might be found in a single valley, and a dozen or more might be maintained by a single agricultural household.[35][36] The European Cultivated Potato Database is an online collaborative database of potato variety descriptions updated and maintained by the Scottish Agricultural Science Agency within the framework of the European Cooperative Programme for Crop Genetic Resources Networks—which is run by the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute.[37] Around 80 varieties are commercially available in the UK.[38]

For culinary purposes, varieties are often differentiated by their waxiness: floury or mealy baking potatoes have more starch (20–22%) than waxy boiling potatoes (16–18%). The distinction may also arise from variation in the comparative ratio of two different potato starch compounds: amylose and amylopectin. Amylose, a long-chain molecule, diffuses from the starch granule when cooked in water, and lends itself to dishes where the potato is mashed. Varieties that contain a slightly higher amylopectin content, which is a highly branched molecule, help the potato retain its shape after being boiled in water.[39] Potatoes that are good for making potato chips or potato crisps are sometimes called "chipping potatoes", which means they meet the basic requirements of similar varietal characteristics, being firm, fairly clean, and fairly well-shaped.[40]

Immature potatoes may be sold fresh from the field as "creamer" or "new" potatoes and are particularly valued for their taste. They are typically small in size and tender, with a loose skin, and flesh containing a lower level of starch than other potatoes. In the United States they are generally either a Yukon Gold potato or a red potato, called gold creamers or red creamers respectively.[41][42] In the UK, the Jersey Royal is a famous type of new potato.[43]

Dozens of potato cultivars have been selectively bred specifically for their skin or flesh color, including gold, red, and blue varieties.[44] These contain varying amounts of phytochemicals, including carotenoids for gold/yellow or polyphenols for red or blue cultivars.[45] Carotenoid compounds include provitamin A alpha-carotene and beta-carotene, which are converted to the essential nutrient, vitamin A, during digestion. Anthocyanins mainly responsible for red or blue pigmentation in potato cultivars do not have nutritional significance, but are used for visual variety and consumer appeal.[46] In 2010, potatoes were bioengineered specifically for these pigmentation traits.[47]

Genetic engineering

Genetic research has produced several genetically modified varieties. 'New Leaf', owned by Monsanto Company, incorporates genes from Bacillus thuringiensis (source of most Bt toxins in transcrop use), which confers resistance to the Colorado potato beetle; 'New Leaf Plus' and 'New Leaf Y', approved by US regulatory agencies during the 1990s, also include resistance to viruses. McDonald's, Burger King, Frito-Lay, and Procter & Gamble announced they would not use genetically modified potatoes, and Monsanto published its intent to discontinue the line in March 2001.[48]

Potato starch contains two types of glucan, amylose and amylopectin, the latter of which is most industrially useful. Waxy potato varieties produce waxy potato starch, which is almost entirely amylopectin, with little or no amylose. BASF developed the 'Amflora' potato, which was modified to express antisense RNA to inactivate the gene for granule bound starch synthase, an enzyme which catalyzes the formation of amylose.[49] 'Amflora' potatoes therefore produce starch consisting almost entirely of amylopectin, and are thus more useful for the starch industry. In 2010, the European Commission cleared the way for 'Amflora' to be grown in the European Union for industrial purposes only—not for food. Nevertheless, under EU rules, individual countries have the right to decide whether they will allow this potato to be grown on their territory. Commercial planting of 'Amflora' was expected in the Czech Republic and Germany in the spring of 2010, and Sweden and the Netherlands in subsequent years.[50]

The 'Fortuna' GM potato variety developed by BASF was made resistant to late blight by introgressing two resistance genes, blb1 and blb2, from S. bulbocastanum, a wild potato native to Mexico.[51][52][53] Rpi-blb1 is a nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NB-LRR/NLR), an R-gene-produced immunoreceptor.[51]

In October 2011 BASF requested cultivation and marketing approval as a feed and food from the EFSA. In 2012, GMO development in Europe was stopped by BASF.[54][55] In November 2014, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) approved a genetically modified potato developed by Simplot, which contains genetic modifications that prevent bruising and produce less acrylamide when fried than conventional potatoes; the modifications do not cause new proteins to be made, but rather prevent proteins from being made via RNA interference.[56]

Genetically modified varieties have met public resistance in the U.S. and in the European Union.[57][58]

Cultivation

Seed potatoes

Potatoes are generally grown from "seed potatoes", tubers specifically grown to be free from disease[clarification needed] and to provide consistent and healthy plants. To be disease free, the areas where seed potatoes are grown are selected with care. In the US, this restricts production of seed potatoes to only 15 states out of all 50 states where potatoes are grown. These locations are selected for their cold, hard winters that kill pests and summers with long sunshine hours for optimum growth.[59] In the UK, most seed potatoes originate in Scotland, in areas where westerly winds reduce aphid attacks and the spread of potato virus pathogens.[60]

Phases of growth

Potato growth can be divided into five phases. During the first phase, sprouts emerge from the seed potatoes and root growth begins. During the second, photosynthesis begins as the plant develops leaves and branches above-ground and stolons develop from lower leaf axils on the below-ground stem. In the third phase the tips of the stolons swell, forming new tubers, and the shoots continue to grow, with flowers typically developing soon after. Tuber bulking occurs during the fourth phase, when the plant begins investing the majority of its resources in its newly formed tubers. At this phase, several factors are critical to a good yield: optimal soil moisture and temperature, soil nutrient availability and balance, and resistance to pest attacks. The fifth phase is the maturation of the tubers: the leaves and stems senesce and the tuber skins harden.[61][62]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Creamer_potato

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk