A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Rhetoric |

|---|

|

Rhetoric (/ˈrɛtərɪk/) is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse (trivium) along with grammar and logic/dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or writers use to inform, persuade, and motivate their audiences.[1] Rhetoric also provides heuristics for understanding, discovering, and developing arguments for particular situations.

Aristotle defined rhetoric as "the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion", and since mastery of the art was necessary for victory in a case at law, for passage of proposals in the assembly, or for fame as a speaker in civic ceremonies, he called it "a combination of the science of logic and of the ethical branch of politics".[2] Aristotle also identified three persuasive audience appeals: logos, pathos, and ethos. The five canons of rhetoric, or phases of developing a persuasive speech, were first codified in classical Rome: invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery.

From Ancient Greece to the late 19th century, rhetoric played a central role in Western education in training orators, lawyers, counsellors, historians, statesmen, and poets.[3][note 1]

Uses

Scope

Scholars have debated the scope of rhetoric since ancient times. Although some have limited rhetoric to the specific realm of political discourse, to many modern scholars it encompasses every aspect of culture. Contemporary studies of rhetoric address a much more diverse range of domains than was the case in ancient times. While classical rhetoric trained speakers to be effective persuaders in public forums and in institutions such as courtrooms and assemblies, contemporary rhetoric investigates human discourse writ large. Rhetoricians have studied the discourses of a wide variety of domains, including the natural and social sciences, fine art, religion, journalism, digital media, fiction, history, cartography, and architecture, along with the more traditional domains of politics and the law.[5]

Because the ancient Greeks valued public political participation, rhetoric emerged as an important curriculum for those desiring to influence politics. Rhetoric is still associated with its political origins. However, even the original instructors of Western speech—the Sophists—disputed this limited view of rhetoric. According to Sophists like Gorgias, a successful rhetorician could speak convincingly on a topic in any field, regardless of his experience in that field. This suggested rhetoric could be a means of communicating any expertise, not just politics. In his Encomium to Helen, Gorgias even applied rhetoric to fiction by seeking, for his amusement, to prove the blamelessness of the mythical Helen of Troy in starting the Trojan War.[6]

Plato defined the scope of rhetoric according to his negative opinions of the art. He criticized the Sophists for using rhetoric to deceive rather than to discover truth. In Gorgias, one of his Socratic Dialogues, Plato defines rhetoric as the persuasion of ignorant masses within the courts and assemblies.[7] Rhetoric, in Plato's opinion, is merely a form of flattery and functions similarly to culinary arts, which mask the undesirability of unhealthy food by making it taste good. Plato considered any speech of lengthy prose aimed at flattery as within the scope of rhetoric. Some scholars, however, contest the idea that Plato despised rhetoric and instead view his dialogues as a dramatization of complex rhetorical principles.[8]

Aristotle both redeemed rhetoric from his teacher and narrowed its focus by defining three genres of rhetoric—deliberative, forensic or judicial, and epideictic.[9] Yet, even as he provided order to existing rhetorical theories, Aristotle generalized the definition of rhetoric to be the ability to identify the appropriate means of persuasion in a given situation based upon the art of rhetoric (technê).[10] This made rhetoric applicable to all fields, not just politics. Aristotle viewed the enthymeme based upon logic (especially, based upon the syllogism) as the basis of rhetoric.

Aristotle also outlined generic constraints that focused the rhetorical art squarely within the domain of public political practice. He restricted rhetoric to the domain of the contingent or probable: those matters that admit multiple legitimate opinions or arguments.[11]

Since the time of Aristotle, logic has changed. For example, modal logic has undergone a major development that also modifies rhetoric.[12]

The contemporary neo-Aristotelian and neo-Sophistic positions on rhetoric mirror the division between the Sophists and Aristotle. Neo-Aristotelians generally study rhetoric as political discourse, while the neo-Sophistic view contends that rhetoric cannot be so limited. Rhetorical scholar Michael Leff characterizes the conflict between these positions as viewing rhetoric as a "thing contained" versus a "container". The neo-Aristotelian view threatens the study of rhetoric by restraining it to such a limited field, ignoring many critical applications of rhetorical theory, criticism, and practice. Simultaneously, the neo-Sophists threaten to expand rhetoric beyond a point of coherent theoretical value.

In more recent years, people studying rhetoric have tended to enlarge its object domain beyond speech. Kenneth Burke asserted humans use rhetoric to resolve conflicts by identifying shared characteristics and interests in symbols. People engage in identification, either to assign themselves or another to a group. This definition of rhetoric as identification broadens the scope from strategic and overt political persuasion to the more implicit tactics of identification found in an immense range of sources[specify].[13]

Among the many scholars who have since pursued Burke's line of thought, James Boyd White sees rhetoric as a broader domain of social experience in his notion of constitutive rhetoric. Influenced by theories of social construction, White argues that culture is "reconstituted" through language. Just as language influences people, people influence language. Language is socially constructed, and depends on the meanings people attach to it. Because language is not rigid and changes depending on the situation, the very usage of language is rhetorical. An author, White would say, is always trying to construct a new world and persuading his or her readers to share that world within the text.[14]

People engage in rhetoric any time they speak or produce meaning. Even in the field of science, via practices which were once viewed as being merely the objective testing and reporting of knowledge, scientists persuade their audience to accept their findings by sufficiently demonstrating that their study or experiment was conducted reliably and resulted in sufficient evidence to support their conclusions.[citation needed]

The vast scope of rhetoric is difficult to define. Political discourse remains the paradigmatic example for studying and theorizing specific techniques and conceptions of persuasion or rhetoric.[15]

As a civic art

Throughout European History, rhetoric meant persuasion in public and political settings such as assemblies and courts.[citation needed] Because of its associations with democratic institutions, rhetoric is commonly said to flourish in open and democratic societies with rights of free speech, free assembly, and political enfranchisement for some portion of the population.[citation needed] Those who classify rhetoric as a civic art believe that rhetoric has the power to shape communities, form the character of citizens, and greatly affect civic life.

Rhetoric was viewed as a civic art by several of the ancient philosophers. Aristotle and Isocrates were two of the first to see rhetoric in this light. In Antidosis, Isocrates states, "We have come together and founded cities and made laws and invented arts; and, generally speaking, there is no institution devised by man which the power of speech has not helped us to establish."[This quote needs a citation] With this statement he argues that rhetoric is a fundamental part of civic life in every society and that it has been necessary in the foundation of all aspects of society. He further argues in Against the Sophists that rhetoric, although it cannot be taught to just anyone, is capable of shaping the character of man. He writes, "I do think that the study of political discourse can help more than any other thing to stimulate and form such qualities of character."[This quote needs a citation] Aristotle, writing several years after Isocrates, supported many of his arguments and argued for rhetoric as a civic art.

In the words of Aristotle, in the Rhetoric, rhetoric is "...the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion". According to Aristotle, this art of persuasion could be used in public settings in three different ways: "A member of the assembly decides about future events, a juryman about past events: while those who merely decide on the orator's skill are observers. From this it follows that there are three divisions of oratory—(1) political, (2) forensic, and (3) the ceremonial oratory of display".[16] Eugene Garver, in his critique of Aristotle's Rhetoric, confirms that Aristotle viewed rhetoric as a civic art. Garver writes, "Rhetoric articulates a civic art of rhetoric, combining the almost incompatible properties of techne and appropriateness to citizens."[17] Each of Aristotle's divisions plays a role in civic life and can be used in a different way to affect the polis.

Because rhetoric is a public art capable of shaping opinion, some of the ancients, including Plato found fault in it. They claimed that while it could be used to improve civic life, it could be used just as easily to deceive or manipulate. The masses were incapable of analyzing or deciding anything on their own and would therefore be swayed by the most persuasive speeches. Thus, civic life could be controlled by whoever could deliver the best speech. Plato explores the problematic moral status of rhetoric twice: in Gorgias and in The Phaedrus, a dialogue best-known for its commentary on love.

More trusting in the power of rhetoric to support a republic, the Roman orator Cicero argued that art required something more than eloquence. A good orator needed also to be a good man, a person enlightened on a variety of civic topics. He describes the proper training of the orator in his major text on rhetoric, De Oratore, which he modeled on Plato's dialogues.

Modern works continue to support the claims of the ancients that rhetoric is an art capable of influencing civic life. In Political Style, Robert Hariman claims that "questions of freedom, equality, and justice often are raised and addressed through performances ranging from debates to demonstrations without loss of moral content".[18] James Boyd White argues that rhetoric is capable not only of addressing issues of political interest but that it can influence culture as a whole. In his book, When Words Lose Their Meaning, he argues that words of persuasion and identification define community and civic life. He states that words produce "the methods by which culture is maintained, criticized, and transformed".[14]

Rhetoric remains relevant as a civic art. In speeches, as well as in non-verbal forms, rhetoric continues to be used as a tool to influence communities from local to national levels.

As a political tool

Political parties employ "manipulative rhetoric" to advance their party-line goals and lobbyist agendas. They use it to portray themselves as champions of compassion, freedom, and culture, all while implementing policies that appear to contradict these claims. It serves as a form of political propaganda, presented to sway and maintain public opinion in their favor, and garner a positive image, potentially at the expense of suppressing dissent or criticism. An example of this is the government's actions in freezing bank accounts and regulating internet speech, ostensibly to protect the vulnerable and preserve freedom of expression, despite contradicting values and rights.[19][20][21]

The origins of the rhetoric language begin in Ancient Greece. It originally began by a group named the Sophists, who wanted to teach the Athenians to speak persuasively in order to be able to navigate themselves in the court and senate. What inspired this form of persuasive speech came about through a new form of government, known as democracy, that was being experimented with. Consequently people began to fear that persuasive speech would overpower truth. Aristotle however believed that this technique was an art, and that persuasive speech could have truth and logic embedded within it. In the end, rhetoric speech still remained popular and was used by many scholars and philosophers.[22]

As a course of study

The study of rhetoric trains students to speak and/or write effectively, and to critically understand and analyze discourse. It is concerned with how people use symbols, especially language, to reach agreement that permits coordinated effort.[23]

Rhetoric as a course of study has evolved since its ancient beginnings, and has adapted to the particular exigencies of various times, venues,[24] and applications ranging from architecture to literature.[25] Although the curriculum has transformed in a number of ways, it has generally emphasized the study of principles and rules of composition as a means for moving audiences.

Rhetoric began as a civic art in Ancient Greece where students were trained to develop tactics of oratorical persuasion, especially in legal disputes. Rhetoric originated in a school of pre-Socratic philosophers known as the Sophists c. 600 BCE. Demosthenes and Lysias emerged as major orators during this period, and Isocrates and Gorgias as prominent teachers. Modern teachings continue to reference these rhetoricians and their work in discussions of classical rhetoric and persuasion.

Rhetoric was taught in universities during the Middle Ages as one of the three original liberal arts or trivium (along with logic and grammar).[26] During the medieval period, political rhetoric declined as republican oratory died out and the emperors of Rome garnered increasing authority. With the rise of European monarchs, rhetoric shifted into courtly and religious applications. Augustine exerted strong influence on Christian rhetoric in the Middle Ages, advocating the use of rhetoric to lead audiences to truth and understanding, especially in the church. The study of liberal arts, he believed, contributed to rhetorical study: "In the case of a keen and ardent nature, fine words will come more readily through reading and hearing the eloquent than by pursuing the rules of rhetoric."[27] Poetry and letter writing became central to rhetorical study during the Middle Ages.[28]: 129–47 After the fall of the Roman republic, poetry became a tool for rhetorical training since there were fewer opportunities for political speech.[28]: 131 Letter writing was the primary way business was conducted both in state and church, so it became an important aspect of rhetorical education.[29]

Rhetorical education became more restrained as style and substance separated in 16th-century France, and attention turned to the scientific method. Influential scholars like Peter Ramus argued that the processes of invention and arrangement should be elevated to the domain of philosophy, while rhetorical instruction should be chiefly concerned with the use of figures and other forms of the ornamentation of language. Scholars such as Francis Bacon developed the study of "scientific rhetoric"[30] which rejected the elaborate style characteristic of classical oration. This plain language carried over to John Locke's teaching, which emphasized concrete knowledge and steered away from ornamentation in speech, further alienating rhetorical instruction—which was identified wholly with such ornamentation—from the pursuit of knowledge.

In the 18th century, rhetoric assumed a more social role, leading to the creation of new education systems (predominantly in England): "Elocution schools" in which girls and women analyzed classic literature, most notably the works of William Shakespeare, and discussed pronunciation tactics.[31]

The study of rhetoric underwent a revival with the rise of democratic institutions during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Hugh Blair was a key early leader of this movement. In his most famous work, Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres, he advocates rhetorical study for common citizens as a resource for social success. Many American colleges and secondary schools used Blair's text throughout the 19th century to train students of rhetoric.[29]

Political rhetoric also underwent renewal in the wake of the U.S. and French revolutions. The rhetorical studies of ancient Greece and Rome were resurrected as speakers and teachers looked to Cicero and others to inspire defenses of the new republics. Leading rhetorical theorists included John Quincy Adams of Harvard, who advocated the democratic advancement of rhetorical art. Harvard's founding of the Boylston Professorship of Rhetoric and Oratory sparked the growth of the study of rhetoric in colleges across the United States.[29] Harvard's rhetoric program drew inspiration from literary sources to guide organization and style, and studies the rhetoric used in political communication to illustrate how political figures persuade audiences.[32] William G. Allen became the first American college professor of rhetoric, at New-York Central College, 1850–1853.

Debate clubs and lyceums also developed as forums in which common citizens could hear speakers and sharpen debate skills. The American lyceum in particular was seen as both an educational and social institution, featuring group discussions and guest lecturers.[33] These programs cultivated democratic values and promoted active participation in political analysis.

Throughout the 20th century, rhetoric developed as a concentrated field of study, with the establishment of rhetorical courses in high schools and universities. Courses such as public speaking and speech analysis apply fundamental Greek theories (such as the modes of persuasion: ethos, pathos, and logos) and trace rhetorical development through history. Rhetoric earned a more esteemed reputation as a field of study with the emergence of Communication Studies departments and of Rhetoric and Composition programs within English departments in universities,[34] and in conjunction with the linguistic turn in Western philosophy. Rhetorical study has broadened in scope, and is especially used by the fields of marketing, politics, and literature.

Another area of rhetoric is the study of cultural rhetorics, which is the communication that occurs between cultures and the study of the way members of a culture communicate with each other.[35] These ideas[specify] can then be studied and understood by other cultures, in order to bridge gaps in modes of communication and help different cultures communicate effectively with each other. James Zappen defines cultural rhetorics as the idea that rhetoric is concerned with negotiation and listening, not persuasion, which differs from ancient definitions.[35] Some ancient rhetoric was disparaged because its persuasive techniques could be used to teach falsehoods.[36] Communication as studied in cultural rhetorics is focused on listening and negotiation, and has little to do with persuasion.[35]

Canons

Rhetorical education focused on five canons. The Five Canons of Rhetoric serve as a guide to creating persuasive messages and arguments:

- inventio (invention)

- the process that leads to the development and refinement of an argument.

- dispositio (disposition, or arrangement)

- used to determine how an argument should be organized for greatest effect, usually beginning with the exordium

- elocutio (style)

- determining how to present the arguments

- memoria (memory)

- the process of learning and memorizing the speech and persuasive messages

- pronuntiatio (presentation) and actio (delivery)

- the gestures, pronunciation, tone, and pace used when presenting the persuasive arguments—the Grand Style.

Memory was added much later to the original four canons.[37]

Music

During the Renaissance rhetoric enjoyed a resurgence, and as a result nearly every author who wrote about music before the Romantic era discussed rhetoric.[38] Joachim Burmeister wrote in 1601, "there is only little difference between music and the nature of oration".[This quote needs a citation] Christoph Bernhard in the latter half of the century said "...until the art of music has attained such a height in our own day, that it may indeed be compared to a rhetoric, in view of the multitude of figures"[needs context].[39]

Knowledge

Epistemology and rhetoric have been compared to one another for decades, but the specifications of their similarities have gone undefined. Since scholar Robert L. Scott stated that, "rhetoric is epistemic,"[40] rhetoricians and philosophers alike have struggled to concretely define the expanse of implications these words hold. Those who have identified this inconsistency maintain the idea that Scott's relation is important, but requires further study.[41]

The root of the issue lies in the ambiguous use of the term rhetoric itself, as well as the epistemological terms knowledge, certainty, and truth.[41] Though counterintuitive and vague, Scott's claims are accepted by some academics, but are then used to draw different conclusions. Sonja K. Foss, for example, takes on the view that, "rhetoric creates knowledge,"[42] whereas James Herrick writes that rhetoric assists in people's ability to form beliefs, which are defined as knowledge once they become widespread in a community.[43]

It is unclear whether Scott holds that certainty is an inherent part of establishing knowledge, his references to the term abstract.[40][44] He is not the only one, as the debate's persistence in philosophical circles long predates his addition of rhetoric. There is an overwhelming majority that does support the concept of certainty as a requirement for knowledge, but it is at the definition of certainty where parties begin to diverge. One definition maintains that certainty is subjective and feeling-based, the other that it is a byproduct of justification.

The more commonly accepted definition of rhetoric claims it is synonymous with persuasion. For rhetorical purposes, this definition, like many others, is too broad. The same issue presents itself with definitions that are too narrow. Rhetoricians in support of the epistemic view of rhetoric have yet to agree in this regard.[41]

Philosophical teachings refer to knowledge as a justified true belief. However, the Gettier Problem explores the room for fallacy in this concept.[45] Therefore, the Gettier Problem impedes the effectivity of the argument of Richard A. Cherwitz and James A. Hikins,[46] who employ the justified true belief standpoint in their argument for rhetoric as epistemic. Celeste Condit Railsback takes a different approach,[47] drawing from Ray E. McKerrow's system of belief based on validity rather than certainty.[48]

William D. Harpine refers to the issue of unclear definitions that occurs in the theories of "rhetoric is epistemic" in his 2004 article "What Do You Mean, Rhetoric is Epistemic?".[41] In it, he focuses on uncovering the most appropriate definitions for the terms "rhetoric", "knowledge", and "certainty". According to Harpine, certainty is either objective or subjective. Although both Scotts[40] and Cherwitz and Hikins[46] theories deal with some form of certainty, Harpine believes that knowledge is not required to be neither objectively nor subjectively certain. In terms of "rhetoric", Harpine argues that the definition of rhetoric as "the art of persuasion" is the best choice in the context of this theoretical approach of rhetoric as epistemic. Harpine then proceeds to present two methods of approaching the idea of rhetoric as epistemic based on the definitions presented. One centers on Alston's[49] view that one's beliefs are justified if formed by one's normal doxastic while the other focuses on the causal theory of knowledge.[50] Both approaches manage to avoid Gettier's problems and do not rely on unclear conceptions of certainty.

In the discussion of rhetoric and epistemology, comes the question of ethics. Is it ethical for rhetoric to present itself in the branch of knowledge? Scott rears this question, addressing the issue, not with ambiguity in the definitions of other terms, but against subjectivity regarding certainty. Ultimately, according to Thomas O. Sloane, rhetoric and epistemology exist as counterparts, working towards the same purpose of establishing knowledge, with the common enemy of subjective certainty.[51]

History and development

Rhetoric is a persuasive speech that holds people to a common purpose and therefore facilitates collective action. During the fifth century BCE, Athens had become active in metropolis and people all over there. During this time the Greek city state had been experimenting with a new form of government- democracy, demos, "the people". Political and cultural identity had been tied to the city area - the citizens of Athens formed institutions to the red processes: are the Senate, jury trials, and forms of public discussions, but people needed to learn how to navigate these new institutions. With no forms of passing on the information, other than word of mouth the Athenians needed an effective strategy to inform the people. A group of wandering Sicilian's later known as the Sophists, began teaching the Athenians persuasive speech, with the goal of navigating the courts and senate. The sophists became speech teachers known as Sophia; Greek for "wisdom" and root for philosophy, or "love of wisdom" - the sophists came to be common term for someone who sold wisdom for money.[52] although there is no clear understanding why the Sicilians engaged to educating the Athenians persuasive speech. It is known that the Athenians did, indeed rely on persuasive speech, more during public speak, and four new political processes, also increasing the sophists trainings leading too many victories for legal cases, public debate, and even a simple persuasive speech. This ultimately led to concerns rising on falsehood over truth, with highly trained, persuasive speakers, knowingly, misinforming.[52]

Rhetoric has its origins in Mesopotamia.[53] Some of the earliest examples of rhetoric can be found in the Akkadian writings of the princess and priestess Enheduanna (c. 2285–2250 BCE).[54] As the first named author in history,[53][54] Enheduanna's writing exhibits numerous rhetorical features that would later become canon in Ancient Greece. Enheduanna's "The Exaltation of Inanna," includes an exordium, argument, and peroration,[53] as well as elements of ethos, pathos, and logos,[54] and repetition and metonymy.[55] She is also known for describing her process of invention in "The Exaltation of Inanna," moving between first- and third-person address to relate her composing process in collaboration with the goddess Inanna,[54] reflecting a mystical enthymeme[56] in drawing upon a Cosmic audience.[54]

Later examples of early rhetoric can be found in the Neo-Assyrian Empire during the time of Sennacherib (704–681 BCE).[57]

In ancient Egypt, rhetoric had existed since at least the Middle Kingdom period (c. 2080–1640 BCE). The five canons of eloquence in ancient Egyptian rhetoric were silence, timing, restraint, fluency, and truthfulness.[58] The Egyptians held eloquent speaking in high esteem. Egyptian rules of rhetoric specified that "knowing when not to speak is essential, and very respected, rhetorical knowledge", making rhetoric a "balance between eloquence and wise silence". They also emphasized "adherence to social behaviors that support a conservative status quo" and they held that "skilled speech should support, not question, society".[59]

In ancient China, rhetoric dates back to the Chinese philosopher, Confucius (551–479 BCE). The tradition of Confucianism emphasized the use of eloquence in speaking.[60]

The use of rhetoric can also be found in the ancient Biblical tradition.[61]

Ancient Greece

In Europe, organized thought about public speaking began in ancient Greece.[62]

In ancient Greece, the earliest mention of oratorical skill occurs in Homer's Iliad, in which heroes like Achilles, Hector, and Odysseus were honored for their ability to advise and exhort their peers and followers (the Laos or army) to wise and appropriate action. With the rise of the democratic polis, speaking skill was adapted to the needs of the public and political life of cities in ancient Greece. Greek citizens used oratory to make political and judicial decisions, and to develop and disseminate philosophical ideas. For modern students, it can be difficult to remember that the wide use and availability of written texts is a phenomenon that was just coming into vogue in Classical Greece. In Classical times, many of the great thinkers and political leaders performed their works before an audience, usually in the context of a competition or contest for fame, political influence, and cultural capital. In fact, many of them are known only through the texts that their students, followers, or detractors wrote down. Rhetor was the Greek term for "orator": A rhetor was a citizen who regularly addressed juries and political assemblies and who was thus understood to have gained some knowledge about public speaking in the process, though in general facility with language was often referred to as logôn techne, "skill with arguments" or "verbal artistry".[63][page needed]

Possibly the first study about the power of language may be attributed to the philosopher Empedocles (d. c. 444 BCE), whose theories on human knowledge would provide a basis for many future rhetoricians. The first written manual is attributed to Corax and his pupil Tisias. Their work, as well as that of many of the early rhetoricians, grew out of the courts of law; Tisias, for example, is believed to have written judicial speeches that others delivered in the courts.

Rhetoric evolved as an important art, one that provided the orator with the forms, means, and strategies for persuading an audience of the correctness of the orator's arguments. Today the term rhetoric can be used at times to refer only to the form of argumentation, often with the pejorative connotation that rhetoric is a means of obscuring the truth. Classical philosophers believed quite the contrary: the skilled use of rhetoric was essential to the discovery of truths, because it provided the means of ordering and clarifying arguments.

Sophists

Teaching in oratory was popularized in the 5th century BCE by itinerant teachers known as sophists, the best known of whom were Protagoras (c. 481–420 BCE), Gorgias (c. 483–376 BCE), and Isocrates (436–338 BCE). Aspasia of Miletus is believed to be one of the first women to engage in private and public rhetorical activities as a Sophist.[64][page needed] The Sophists were a disparate group who travelled from city to city, teaching in public places to attract students and offer them an education. Their central focus was on logos, or what we might broadly refer to as discourse, its functions and powers.[citation needed] They defined parts of speech, analyzed poetry, parsed close synonyms, invented argumentation strategies, and debated the nature of reality.[citation needed] They claimed to make their students better, or, in other words, to teach virtue. They thus claimed that human excellence was not an accident of fate or a prerogative of noble birth, but an art or "techne" that could be taught and learned. They were thus among the first humanists.[citation needed]

Several Sophists also questioned received wisdom about the gods and the Greek culture, which they believed was taken for granted by Greeks of their time, making these Sophists among the first agnostics. For example, they argued that cultural practices were a function of convention or nomos rather than blood or birth or phusis.[citation needed] They argued further that the morality or immorality of any action could not be judged outside of the cultural context within which it occurred. The well-known phrase, "Man is the measure of all things" arises from this belief.[citation needed] One of the Sophists' most famous, and infamous, doctrines has to do with probability and counter arguments. They taught that every argument could be countered with an opposing argument, that an argument's effectiveness derived from how "likely" it appeared to the audience (its probability of seeming true), and that any probability argument could be countered with an inverted probability argument. Thus, if it seemed likely that a strong, poor man were guilty of robbing a rich, weak man, the strong poor man could argue, on the contrary, that this very likelihood (that he would be a suspect) makes it unlikely that he committed the crime, since he would most likely be apprehended for the crime.[citation needed] They also taught and were known for their ability to make the weaker (or worse) argument the stronger (or better).[citation needed] Aristophanes famously parodies the clever inversions that sophists were known for in his play The Clouds.[citation needed]

The word "sophistry" developed negative connotations in ancient Greece that continue today, but in ancient Greece Sophists were nevertheless popular and well-paid professionals, respected for their abilities but also criticized for their excesses.

According to William Keith and Christian Lundberg, as the Greek society shifted towards more democratic values, the Sophists were responsible for teaching the newly democratic Greek society the importance of persuasive speech and strategic communication for its new governmental institutions.[65]

Isocrates

Isocrates (436–338 BCE), like the Sophists, taught public speaking as a means of human improvement, but he worked to distinguish himself from the Sophists, whom he saw as claiming far more than they could deliver. He suggested that while an art of virtue or excellence did exist, it was only one piece, and the least, in a process of self-improvement that relied much more on native talent, desire, constant practice, and the imitation of good models. Isocrates believed that practice in speaking publicly about noble themes and important questions would improve the character of both speaker and audience while also offering the best service to a city. Isocrates was an outspoken champion of rhetoric as a mode of civic engagement.[66] He thus wrote his speeches as "models" for his students to imitate in the same way that poets might imitate Homer or Hesiod, seeking to inspire in them a desire to attain fame through civic leadership. His was the first permanent school in Athens and it is likely that Plato's Academy and Aristotle's Lyceum were founded in part as a response to Isocrates. Though he left no handbooks, his speeches ("Antidosis" and "Against the Sophists" are most relevant to students of rhetoric) became models of oratory and keys to his entire educational program. He was one of the canonical "Ten Attic Orators". He influenced Cicero and Quintilian, and through them, the entire educational system of the west.

Plato

Plato (427–347 BCE) outlined the differences between true and false rhetoric in a number of dialogues—particularly the Gorgias and Phaedrus, dialogues in which Plato disputes the sophistic notion that the art of persuasion (the Sophists' art, which he calls "rhetoric"), can exist independent of the art of dialectic. Plato claims that since Sophists appeal only to what seems probable, they are not advancing their students and audiences, but simply flattering them with what they want to hear. While Plato's condemnation of rhetoric is clear in the Gorgias, in the Phaedrus he suggests the possibility of a true art wherein rhetoric is based upon the knowledge produced by dialectic. He relies on a dialectically informed rhetoric to appeal to the main character, Phaedrus, to take up philosophy. Thus Plato's rhetoric is actually dialectic (or philosophy) "turned" toward those who are not yet philosophers and are thus unready to pursue dialectic directly. Plato's animosity against rhetoric, and against the Sophists, derives not only from their inflated claims to teach virtue and their reliance on appearances, but from the fact that his teacher, Socrates, was sentenced to death after Sophists' efforts.

Some scholars, however, see Plato not as an opponent of rhetoric but rather as a nuanced rhetorical theorist who dramatized rhetorical practice in his dialogues and imagined rhetoric as more than just oratory.[8]

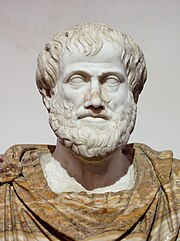

Aristotle

Aristotle: Rhetoric is an antistrophes to dialectic. "Let rhetoric an ability

, in each case, to see the available means of persuasion." "Rhetoric is a

counterpart of dialectic" — an art of practical civic reasoning, applied to deliberative,

judicial, and "display" speeches in political assemblies, lawcourts, and other public

gatherings

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2013) |

Aristotle (384–322 BCE) was a student of Plato who set forth an extended treatise on rhetoric that still repays careful study today. In the first sentence of The Art of Rhetoric, Aristotle says that "rhetoric is the antistrophe of dialectic".[67]: I.1 As the "antistrophe" of a Greek ode responds to and is patterned after the structure of the "strophe" (they form two sections of the whole and are sung by two parts of the chorus), so the art of rhetoric follows and is structurally patterned after the art of dialectic because both are arts of discourse production. While dialectical methods are necessary to find truth in theoretical matters, rhetorical methods are required in practical matters such as adjudicating somebody's guilt or innocence when charged in a court of law, or adjudicating a prudent course of action to be taken in a deliberative assembly.

For Plato and Aristotle, dialectic involves persuasion, so when Aristotle says that rhetoric is the antistrophe of dialectic, he means that rhetoric as he uses the term has a domain or scope of application that is parallel to, but different from, the domain or scope of application of dialectic. Claude Pavur explains that "he Greek prefix 'anti' does not merely designate opposition, but it can also mean 'in place of'".[68]

Aristotle's treatise on rhetoric systematically describes civic rhetoric as a human art or skill (techne). It is more of an objective theory[clarification needed] than it is an interpretive theory with a rhetorical tradition. Aristotle's art of rhetoric emphasizes persuasion as the purpose of rhetoric. His definition of rhetoric as "the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion", essentially a mode of discovery, limits the art to the inventional process; Aristotle emphasizes the logical aspect of this process. A speaker supports the probability of a message by logical, ethical, and emotional proofs.

Aristotle identifies three steps or "offices" of rhetoric—invention, arrangement, and style—and three different types of rhetorical proof:[67]: I.2

- ethos

- Aristotle's theory of character and how the character and credibility of a speaker can influence an audience to consider him/her to be believable—there being three qualities that contribute to a credible ethos: perceived intelligence, virtuous character, and goodwill

- pathos

- the use of emotional appeals to alter the audience's judgment through metaphor, amplification, storytelling, or presenting the topic in a way that evokes strong emotions in the audience

- logos

- the use of reasoning, either inductive or deductive, to construct an argument

Aristotle emphasized enthymematic reasoning as central to the process of rhetorical invention, though later rhetorical theorists placed much less emphasis on it. An "enthymeme" follows the form of a syllogism, however it excludes either the major or minor premise. An enthymeme is persuasive because the audience provides the missing premise. Because the audience participates in providing the missing premise, they are more likely to be persuaded by the message.

Aristotle identified three different types or genres of civic rhetoric:[67]: I.3

- Forensic (also known as judicial) Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Classical_rhetoric

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk