A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Arrow worms Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Chaetognatha and some examples of their diversity. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Clade: | Nephrozoa |

| (unranked): | Protostomia |

| (unranked): | Spiralia |

| Clade: | Gnathifera |

| Phylum: | Chaetognatha Leuckart, 1854 |

| Class: | Sagittoidea Claus & Grobben, 1905 [2] |

| Orders | |

The Chaetognatha /kiːˈtɒɡnəθə/ or chaetognaths /ˈkiːtɒɡnæθs/ (meaning bristle-jaws) are a phylum of predatory marine worms that are a major component of plankton worldwide. Commonly known as arrow worms, they are mostly nektonic; however about 20% of the known species are benthic, and can attach to algae and rocks. They are found in all marine waters, from surface tropical waters and shallow tide pools to the deep sea and polar regions. Most chaetognaths are transparent and are torpedo shaped, but some deep-sea species are orange. They range in size from 2 to 120 millimetres (0.1 to 4.7 in).

Chaetognaths were first recorded by the Dutch naturalist Martinus Slabber in 1775.[3] As of 2021, biologists recognize 133 modern species assigned to over 26 genera and eight families.[3] Despite the limited diversity of species, the number of individuals is large.[4]

Arrow worms are strictly related to and possibly belonging to Gnathifera, a clade of protostomes that do not belong to either Ecdysozoa or Lophotrochozoa.

Anatomy

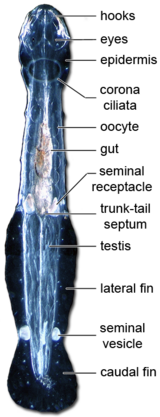

Chaetognaths are transparent or translucent dart-shaped animals covered by a cuticle. They range in length between 1.5 mm to 105 mm in the Antarctic species Pseudosagitta gazellae.[5] Body size, either between individuals in the same species or between different species, seems to increase with decreasing temperature.[5] The body is divided into a distinct head, trunk, and tail. About 80% of the body is occupied by primary longitudinal muscles.[3]

Head and digestive system

There are between four and fourteen hooked, grasping spines on each side of their head, flanking a hollow vestibule containing the mouth. The spines are used in hunting, and covered with a flexible hood arising from the neck region when the animal is swimming. Spines and teeth are made of α-chitin, and the head is protected by a chitinous armature.[3]

The mouth opens into a muscular pharynx, which contains glands to lubricate the passage of food. From here, a straight intestine runs the length of the trunk to an anus just forward of the tail. The intestine is the primary site of digestion and includes a pair of diverticula near the anterior end.[6] Materials are moved about the body cavity by cilia. Waste materials are simply excreted through the skin and anus. Eukrohniid species possess an oil vacuole closely associated with the gut. This organ contains wax esters which may assist reproduction and growth outside of the production season for Eukrohnia hamata in Arctic seas.[7] Owing to the position of the oil vacuole in the center of the tractus, the organ may also have implications for buoyancy, trim and locomotion.[8]

Usually chaetognaths are not pigmented, however the intestines of some deep-sea species contain orange-red carotenoid pigments.[3]

Nervous and sensory systems

The nervous system is reasonably simple and shows a typical protostome anatomy,[3] consisting of a ganglionated nerve ring surrounding the pharynx. The brain is composed of two distinct functional domains: the anterior neuropil domain and the posterior neuropil domain. The former probably controls head muscles moving the spines and the digestive system. The latter is linked to eyes and the corona ciliata. A putative sensory structure of unknown function, the retrocerebral organ, is also hosted by the posterior neuropil domain.[3] The dorsal ganglion is the largest, but nerves extend from all the ganglia along the length of the body.

Chaetognaths have two compound eyes, each consisting of a number of pigment-cup ocelli fused together; some deep-sea and troglobitic species have unpigmented or absent eyes.[3] In addition, there are a number of sensory bristles arranged in rows along the side of the body, where they probably perform a function similar to that of the lateral line in fish. An additional, curved, band of sensory bristles lies over the head and neck.[6] Almost all chaetognaths have "indirect" or "inverted" eyes, according to the orientation of photoreceptor cells; only some Eukhroniidae species have "direct" or "everted" eyes.[3] A unique feature of the chaetognath eye is the lamellar structure of photoreceptor membranes, containing a grid of 35-55 nm wide circular pores.[3]

A significant mechanosensory system, composed of ciliary receptor organs, detects vibrations, allowing chaetognaths to detect the swimming motion of potential prey. Another organ on the dorsal part of the neck, the corona ciliata, is probably involved in chemoreception.[3]

Internal organs

The body cavity is lined by peritoneum, and therefore represents a true coelom, and is divided into one compartment on each side of the trunk, and additional compartments inside the head and tail, all separated completely by septa. Although they have a mouth with one or two rows of tiny teeth, compound eyes, and a nervous system, they have no excretory or respiratory systems.[9][3] While often said to lack a circulatory system, chaetognaths do have a rudimentary hemal system resembling those of annelids.[3]

The arrow worm rhabdomeres are derived from microtubules 20 nm long and 50 nm wide, which in turn form conical bodies that contain granules and thread structures. The cone body is derived from a cilium.[10]

Locomotion

The trunk bears one or two pairs of lateral fins incorporating structures superficially similar to the fin rays of fish, with which they are not homologous. Unlike those of vertebrates, these lateral fins are composed of a thickened basement membrane extending from the epidermis. An additional caudal fin covers the post-anal tail.[6] Two chaetognath species, Caecosagitta macrocephala and Eukrohnia fowleri, have bioluminescent organs on their fins.[11][12]

Chaetognaths swim in short bursts using a dorso-ventral undulating body motion, where their tail fin assists with propulsion and the body fins with stabilization and steering.[13] Muscle movements have been described as among the fastest in metazoans.[3] Muscles are directly excitable by electrical currents or strong K+ solutions; the main neuromuscular transmitter is acetylcholine.[3]

Reproduction and life cycle

All species are hermaphroditic, carrying both eggs and sperm.[4] Each animal possesses a pair of testes within the tail, and a pair of ovaries in the posterior region of the main body cavity. Immature sperm are released from the testes to mature inside the cavity of the tail, and then swim through a short duct to a seminal vesicle where they are packaged into a spermatophore.[6]

During mating, each individual places a spermatophore onto the neck of its partner after rupture of the seminal vesicle. The sperm rapidly escape from the spermatophore and swim along the midline of the animal until they reach a pair of small pores just in front of the tail. These pores connect to the oviducts, into which the developed eggs have already passed from the ovaries, and it is here that fertilisation takes place.[6] The seminal receptacles and oviducts accumulate and store spermatozoa, to perform multiple fertilisation cycles.[3] Some benthic members of Spadellidae are known to have elaborate courtship rituals before copulation,[3] for example Paraspadella gotoi.[14]

The eggs are mostly planktonic, except in a few species such as Ferosagitta hispida that attaches eggs to the substrate.[3] In Eukrohnia, eggs develop in marsupial sacs or attached to algae.[15] Eggs usually hatch after 1-3 days. Chaetognaths do not undergo metamorphosis nor they possess a well-defined larval stage,[6][3] an unusual trait among marine invertebrates;[14] however there are significant morphological differences between the newborn and the adult, with respect to proportions, chitinous structures and fin development.[3][16]

The life spans of chaetognaths are variable but short; the longest recorded was 15 months in Sagitta friderici.[16]

Behaviour

Little is known of arrow worms' behaviour and physiology, due to the complexity in culturing them and reconstructing their natural habitat.[3] It is known that they feed more frequently with higher temperatures. Planktonic chaetognaths often must swim continuously, with a "hop and sink" behaviour, to keep themselves in the desired location in the water layer, and swim actively to catch prey. They all tend to keep the body slightly slanted with the head pointing downwards.[3] They often show a "gliding" behaviour, slowly sinking for a while, and then catching up with a quick movement of their fins.[14] Benthic species usually stay attached to substrates such as rocks, algae or sea grasses, more rarely on top or between sand grains, and act more strictly as ambush predators, staying still until prey passes by.[3] The prey is detected thanks to the ciliary fence and tuft organs, sensing vibrations[3] - individuals of Spadella cephaloptera for example will attack a glass or metal probe vibrating at an adequate frequency.[14] To catch prey, arrow worms jump forward with a strong stroke of the tail fin.[3] Once in contact with prey, they withdraw the hood over the grasping spines, so that it forms a cage around the prey and bring it in contact with the mouth. They swallow their prey whole.[14]

Ecology

Chaetognaths are found in all world's oceans, from the poles to tropics, and also in brackish and estuarine waters. They inhabit very diverse environments, from hydrothermal vents to deep ocean seafloor, to seagrass beds and marine caves.[3] The majority are planktonic, and they are often the second most common component of zooplankton, with a biomass ranging between 10 and 30% that of copepods.[3] In the Canada Basin, chaetognaths alone represent ~13% of the zooplankton biomass.[17] As such, they are ecologically relevant and a key food source for fishes and other predators, including commercially relevant fishes such as mackerel or sardines.[18] 58% of known species are pelagic,[5] while about a third of species are epibenthic or meiobenthic, or inhabit the immediate vicinity of the substrate.[3] Chaetognaths have been recorded up to 5000 and possibly even 6000 meters of depth.[5]

The highest density of chaetognaths is observed in the photic zone of shallow waters.[3] Larger chaetognath species tend to live deeper in water, but spend their juvenile stages higher in the water column.[14] Arrow worms however engage in diel vertical migration, spending the day at lower depths to avoid predators, and coming close to the surface at night. Their position in the water column can depend on light, temperature, salinity, age and food supply. They cannot swim against oceanic currents, and they are used as a hydrological indicator of currents and water masses.[3]

All chaetognaths are ambush predators, preying on other planktonic animals, mostly copepods and cladocerans[6][3] but also amphipods, krill and fish larvae.[18] Adults can feed on younger individuals of the same species.[19] Some species are also reported to be omnivores, feeding on algae and detritus.[20] Chaetognaths are known to use the neurotoxin tetrodotoxin to subdue prey,[21] possibly synthesized by Vibrio bacterial species.[3]

Genetics

Mitochondrial genome

The mtDNA of the arrow worm Spadella cephaloptera has been sequenced in 2004, and at the time it was the smallest metazoan mitochondrial genome known, being 11,905 base pairs long[22] (it has now been surpassed by the mitchondrial genome of the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi, which is 10,326 bp long).[23] All mitochondrial tRNA genes are absent. The MT-ATP8 and MT-ATP6 genes are also missing.[22] The mtDNA of Paraspadella gotoi, also sequenced in 2004, is even smaller (11,403 bp) and it shows a similar pattern, lacking 21 of the 22 usually present tRNA genes and featuring only 14 of the 37 genes normally present. [24]

Chaetognaths show a unique mitochondrial genomic diversity within individual of the same species.[25]

Phylogeny

External

The evolutionary relationships of chaetognaths have long been enigmatic. Charles Darwin remarked that arrow worms were "remarkable for the obscurity of their affinities".[14] Chaetognaths in the past have been traditionally, but erroneously, classed as deuterostomes by embryologists due to deuterostome-like features in the embryo. Lynn Margulis and K. V. Schwartz placed chaetognaths in the deuterostomes in their Five Kingdom classification.[27] However, several developmental features are at odds with deuterostomes and are either akin to Spiralia or unique to Chaetognatha.[3]

| Summary of relationships of gnathiferans in recent studies including Chaetognatha within the clade, with disputed relationships represented as polytomies[28][29][30][31][32] |

| |||

| Chaetognaths in the metazoan tree of life, when considered the sister group of Gnathifera.[3] |

Molecular phylogeny shows that Chaetognatha are, in fact, protostomes. Thomas Cavalier-Smith places them in the protostomes in his Six Kingdom classification.[33] The similarities between chaetognaths and nematodes mentioned above may support the protostome thesis—in fact, chaetognaths are sometimes regarded as a basal ecdysozoan or lophotrochozoan.[34] Chaetognatha appears close to the base of the protostome tree in most studies of their molecular phylogeny.[35] This may explain their deuterostome embryonic characters. If chaetognaths branched off from the protostomes before they evolved their distinctive protostome embryonic characters, they might have retained deuterostome characters inherited from early bilaterian ancestors. Thus chaetognaths may be a useful model for the ancestral bilaterian.[36] Studies of arrow worms' nervous systems suggests they should be placed within the protostomes.[37][38] According to 2017 and 2019 papers, chaetognaths either belong to[39][40] or are the sister group of Gnathifera.[3]

Internal

Below is a consensus evolutionary tree of Chaetognatha, based on both morphological and molecular data, as of 2021.[3]