A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Chandogya | |

|---|---|

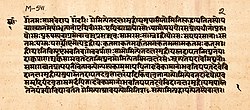

The Chandogya Upanishad verses 1.1.1-1.1.9 (Sanskrit, Devanagari script) | |

| Devanagari | छान्दोग्य |

| IAST | Chāndogya |

| Date | 8th to 6th century BCE |

| Type | Mukhya Upanishad |

| Linked Veda | Samaveda |

| Chapters | Eight |

| Philosophy | Oneness of the Atman |

| Commented by | Adi Shankara, Madhvacharya |

| Popular verse | Tat tvam asi |

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

The Chandogya Upanishad (Sanskrit: छान्दोग्योपनिषद्, IAST: Chāndogyopaniṣad) is a Sanskrit text embedded in the Chandogya Brahmana of the Sama Veda of Hinduism.[1] It is one of the oldest Upanishads.[2] It lists as number 9 in the Muktika canon of 108 Upanishads.[3]

The Upanishad belongs to the Tandya school of the Samaveda.[1] Like Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, the Chandogya is an anthology of texts that must have pre-existed as separate texts, and were edited into a larger text by one or more ancient Indian scholars.[1] The precise chronology of Chandogya Upanishad is uncertain, and it is variously dated to have been composed by the 8th to 6th century BCE in India.[2][4][5]

It is one of the largest Upanishadic compilations, and has eight Prapathakas (literally lectures, chapters), each with many volumes, and each volume contains many verses.[6][7] The volumes are a motley collection of stories and themes. As part of the poetic and chants-focussed Samaveda, the broad unifying theme of the Upanishad is the importance of speech, language, song and chants to man's quest for knowledge and salvation, to metaphysical premises and questions, as well as to rituals.[1][8]

The Chandogya Upanishad is notable for its lilting metric structure, its mention of ancient cultural elements such as musical instruments, and embedded philosophical premises that later served as foundation for Vedanta school of Hinduism.[9] It is one of the most cited texts in later Bhasyas (reviews and commentaries) by scholars from the diverse schools of Hinduism. Adi Shankaracharya, for example, cited Chandogya Upanishad 810 times in his Vedanta Sutra Bhasya, more than any other ancient text.[10]

Etymology

The name of the Upanishad is derived from the word Chanda or chandas, which means "poetic meter, prosody".[6][11] The nature of the text relates to the patterns of structure, stress, rhythm and intonation in language, songs and chants. The text is sometimes known as Chandogyopanishad.[12]

Chronology

Chandogya Upanishad was in all likelihood composed in the earlier part of 1st millennium BCE, and is one of the oldest Upanishads.[4] The exact century of the Upanishad composition is unknown, uncertain and contested.[2]

The chronology of early Upanishads is difficult to resolve due to scant evidence, an analysis of archaism, style, and repetitions across texts, driven by assumptions about likely evolution of ideas, and on presumptions about which philosophy might have influenced which other Indian philosophies.[2] Patrick Olivelle states, "in spite of claims made by some, in reality, any dating of these documents (early Upanishads) that attempts a precision closer than a few centuries is as stable as a house of cards".[4]

The chronology and authorship of Chandogya Upanishad, along with the Brihadaranyaka and Kaushitaki Upanishads, is further complicated because they are compiled anthologies of literature that must have existed as independent texts before they became part of these Upanishads.[13]

Scholars have offered different estimates ranging from 800 BCE to 600 BCE, all preceding Buddhism. According to a 1998 review by Patrick Olivelle. Chandogya was composed by 7th or 6th century BCE, give or take a century or so.[4] Phillips states that Chandogya was completed after Brihadaranyaka, both probably in early part of the 8th century CE.[2]

Structure

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

The text has eight Prapathakas (प्रपाठक, lectures, chapters), each with varying number of Khandas (खण्ड, volume).[7]

Each Khanda has varying number of verses. The first chapter includes 13 volumes each with varying number of verses, the second chapter has 24 volumes, the third chapter contains 19 volumes, the fourth is composed of 17 volumes, the fifth has 24, the sixth chapter has 16 volumes, the seventh includes 26 volumes, and the eight chapter is last with 15 volumes.[7]

The Upanishad comprises the last eight chapters of a ten chapter Chandogya Brahmana text.[14][15] The first chapter of the Brahmana is short and concerns ritual-related hymns to celebrate a marriage ceremony[16] and the birth of a child.[14]

The second chapter of the Brahmana is short as well and its mantras are addressed to divine beings at life rituals. The last eight chapters are long, and are called the Chandogya Upanishad.[14]

A notable structural feature of Chandogya Upanishad is that it contains many nearly identical passages and stories also found in Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, but in precise meter.[17][18]

The Chandogya Upanishad, like other Upanishads, was a living document. Every chapter shows evidence of insertion or interpolation at a later age, because the structure, meter, grammar, style and content is inconsistent with what precedes or follows the suspect content and section. Additionally, supplements were likely attached to various volumes in a different age.[19]

Klaus Witz[who?] structurally divides the Chandogya Upanishad into three natural groups. The first group comprises chapters I and II, which largely deal with the structure, stress and rhythmic aspects of language and its expression (speech), particularly with the syllable Om (ॐ, Aum).[17]

The second group consists of chapters III-V, with a collection of more than 20 Upasanas and Vidyas on premises about the universe, life, mind and spirituality. The third group consists of chapters VI-VIII that deal with metaphysical questions such as the nature of reality and Self.[17]

Content

First Prapāṭhaka

The chant of Om, the essence of all

The Chandogya Upanishad opens with the recommendation that "let a man meditate on Om".[20] It calls the syllable Om as udgitha (उद्गीथ, song, chant), and asserts that the significance of the syllable is thus: the essence of all beings is earth, the essence of earth is water, the essence of water are the plants, the essence of plants is man, the essence of man is speech, the essence of speech is the Rig Veda, the essence of the Rig Veda is the Sama Veda, and the essence of Sama Veda is udgitha.[21]

Rik (ऋच्, Ṛc) is speech, states the text, and Sāman (सामन्) is breath; they are pairs, and because they have love and desire for each other, speech and breath find themselves together and mate to produce song.[20][21] The highest song is Om, asserts volume 1.1 of Chandogya Upanishad. It is the symbol of awe, of reverence, of threefold knowledge because Adhvaryu invokes it, the Hotr recites it, and Udgatr sings it.[21]

In section 1.4, the text highlights the importance of Om in the High Chant.[22]

Good and evil may be everywhere, yet life-principle is inherently good

The second volume of the first chapter continues its discussion of syllable Om, explaining its use as a struggle between Devas (gods) and Asuras (demons) – both being races derived from one Prajapati (creator of life).[25] Max Muller states that this struggle between deities and demons is considered allegorical by ancient scholars, as good and evil inclinations within man, respectively.[26] The Prajapati is man in general, in this allegory.[26] The struggle is explained as a legend, that is also found in a more complete and likely original ancient version in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (chapter 1.3).[25]

The legend in section 1.2 of Chandogya Upanishad states that gods took the Udgitha (song of Om) unto themselves, thinking, "with this we shall overcome the demons".[27] The gods revered the Udgitha as sense of smell, but the demons cursed it and ever since one smells both good-smelling and bad-smelling, because it is afflicted with good and evil.[25] The deities thereafter revered the Udgitha as speech, but the demons afflicted it and ever since one speaks both truth and untruth, because speech has been struck with good and evil.[26] The deities next revered the Udgitha as sense of sight (eye), but the demons struck it and ever since one sees both what is harmonious, sightly and what is chaotic, unsightly, because sight is afflicted with good and evil.[27] The gods then revered the Udgitha as sense of hearing (ear), but the demons afflicted it and ever since one hears both what is worth hearing and what is not worth hearing, because hearing is afflicted with good and evil.[25] The gods thereafter revered the Udgitha as Manas (mind), but the demons afflicted it and therefore one imagines both what is worth imagining and what is not worth imagining, because mind is afflicted with good and evil.[27] Then the gods revered the Udgitha as Prāṇa (vital breath, breath in the mouth, life-principle), and the demons struck it but they fell into pieces. Life-principle is free from evil, it is inherently good.[25][26] The deities inside man – the body organs and senses of man are great, but they all revere the life-principle because it is the essence and the lord of all of them. Om is the Udgitha, the symbol of life-principle in man.[25]

Space: the origin and the end of everything

The Chandogya Upanishad, in eighth and ninth volumes of the first chapter, describes the debate between three men proficient in Udgitha, about the origins and support of Udgitha and all of empirical existence.[28] The debaters summarize their discussion as,

What is the origin of this world?[29]

Space, said he. Verily, all things here arise out of space. They disappear back into space, for space alone is greater than these, space is the final goal. This is the most excellent Udgitha . This is endless. The most excellent is his, the most excellent worlds does he win, who, knowing it thus, reveres the most excellent Udgitha.— Chandogya Upanishad 1.9.1-1.9.2[28]

Max Muller notes the term "space" above, was later asserted in the Vedanta Sutra verse 1.1.22 to be a symbolism for the Vedic concept of Brahman.[29] Paul Deussen explains the term Brahman means the "creative principle which lies realized in the whole world".[30]

A ridicule and satire on egotistic nature of priests

The tenth through twelfth volumes of the first "Prapathaka" of Chandogya Upanishad describe a legend about priests and it criticizes how they go about reciting verses and singing hymns without any idea what they mean or the divine principle they signify.[31] The 12th volume in particular ridicules the egotistical aims of priests through a satire, that is often referred to as "the Udgitha of the dogs".[31][32][33]

The verses 1.12.1 through 1.12.5 describe a convoy of dogs who appear before Vaka Dalbhya (literally, sage who murmurs and hums), who was busy in a quiet place repeating Veda. The dogs ask, "Sir, sing and get us food, we are hungry".[32] The Vedic reciter watches in silence, then the head dog says to other dogs, "come back tomorrow". Next day, the dogs come back, each dog holding the tail of the preceding dog in his mouth, just like priests do holding the gown of preceding priest when they walk in procession.[34] After the dogs settled down, they together began to say, "Him" and then sang, "Om, let us eat! Om, let us drink! Lord of food, bring hither food, bring it!, Om!"[31][35]

Such satire is not unusual in Indian literature and scriptures, and similar emphasis for understanding over superficial recitations is found in other ancient texts, such as chapter 7.103 of the Rig Veda.[31]

John Oman, in his review of the satire in section 1.12 of the Chandogya Upanishad, states, "More than once we have the statement that ritual doings only provide merit in the other world for a time, whereas the right knowledge rids of all questions of merit and secures enduring bliss".[35]

Structure of language and cosmic correspondences

The 13th volume of the first chapter lists mystical meanings in the structure and sounds of a chant.[36] The text asserts that hāu, hāi, ī, atha, iha, ū, e, hiṅ among others correspond to empirical and divine world, such as Moon, wind, Sun, oneself, Agni, Prajapati, and so on. The thirteen syllables listed are "Stobhaksharas", sounds used in musical recitation of hymns, chants and songs.[37] This volume is one of many sections that does not fit with the preceding text or text that follows.

The fourth verse of the 13th volume uses the word Upanishad, which Max Muller translates as "secret doctrine",[37][38] and Patrick Olivelle translates as "hidden connections".[39]

Second Prapāṭhaka

The significance of chant

The first volume of the second chapter states that the reverence for entire Sāman (साम्न, chant) is sādhu (साधु, good), for three reasons. These reasons invoke three different contextual meanings of Saman, namely abundance of goodness or valuable (सामन), friendliness or respect (सम्मान), property goods or wealth (सामन्, also समान).[39][40][41] The Chandogya Upanishad states that the reverse is true too, that people call it a-sāman when there is deficiency or worthlessness (ethics), unkindness or disrespect (human relationships), and lack of wealth (means of life, prosperity).[41][42]

Everything in Universe chants

Volumes 2 through 7 of the second Prapathaka present analogies between various elements of the Universe and elements of a chant.[43] The latter include Hinkāra (हिङ्कार, preliminary vocalizing), Prastāva (प्रस्ताव, propose, prelude, introduction), Udgītha (उद्गीत, sing, chant), Pratihāra (प्रतिहार, response, closing) and Nidhana (निधन, finale, conclusion).[44] The sets of mapped analogies present interrelationships and include cosmic bodies, natural phenomena, hydrology, seasons, living creatures and human physiology.[45] For example, chapter 2.3 of the Upanishad states,

The winds blow, that is Hinkāra

A cloud is formed, that is Prastāva

It rains, that is an Udgītha

The lightning that strikes and thunder that rolls, that is Pratihāra

The rains stop and clouds lift, that is Nidhana.

The eighth volume of the second chapter expands the five-fold chant structure to seven-fold chant structure, wherein Ādi and Upadrava are the new elements of the chant. The day and daily life of a human being is mapped to the seven-fold structure in volumes 2.9 and 2.10 of the Upanishad.[47]

Thereafter, the text returns to five-fold chant structure in volumes 2.11 through 2.21, with the new sections explaining the chant as the natural template for cosmic phenomena, psychological behavior, human copulation, human body structure, domestic animals, divinities and others.[48][49] The metaphorical theme in this volume of verses, asserts Paul Deussen, is that the Universe is an embodiment of Brahman, that the "chant" (Saman) is interwoven into this entire Universe and every phenomenon is a fractal manifestation of the ultimate reality.[48][50] The 22nd volume of the second chapter discusses the structure of vowels (svara), consonants (sparsa) and sibilants (ushman).[49]

The nature of Dharma and Ashramas (stages) theory

The Chandogya Upanishad in volume 23 of chapter 2 provides one of the earliest expositions on the broad, complex meaning of Vedic concept dharma. It includes as dharma – ethical duties such as charity to those in distress (Dāna, दान), personal duties such as education and self study (svādhyāya, स्वाध्याय, brahmacharya, ब्रह्मचर्य), social rituals such as yajna (यज्ञ).[51] The Upanishad describes the three branches of dharma as follows:

त्रयो धर्मस्कन्धा यज्ञोऽध्ययनं दानमिति प्रथम

स्तप एव द्वितीयो ब्रह्मचार्याचार्यकुलवासी तृतीयो

ऽत्यन्तमात्मानमाचार्यकुलेऽवसादयन्सर्व एते पुण्यलोका भवन्ति ब्रह्मसँस्थोऽमृतत्वमेति ॥ १ ॥[52]

There are three branches of Dharma (religious life, duty): Yajna (sacrifice), Svādhyāya (self study) and Dāna (charity) are the first,

Tapas (austerity, meditation) is the second, while dwelling as a Brahmacharya for education in the house of a teacher is third,

All three achieve the blessed worlds. But the Brahmasamstha – one who is firmly grounded in Brahman – alone achieves immortality.

This passage has been widely cited by ancient and medieval Sanskrit scholars as the fore-runner to the asrama or age-based stages of dharmic life in Hinduism.[54][55] The four asramas are: Brahmacharya (student), Grihastha (householder), Vanaprastha (retired) and Sannyasa (renunciation).[56][57] Olivelle disagrees however, and states that even the explicit use of the term asrama or the mention of the "three branches of dharma" in section 2.23 of Chandogya Upanishad does not necessarily indicate that the asrama system was meant.[58]

Paul Deussen [who?] notes that the Chandogya Upanishad, in the above verse, is not presenting these stages as sequential, but rather as equal.[54] Only three stages are explicitly described, Grihastha first, Vanaprastha second and then Brahmacharya third.[55] Yet the verse also mentions the person in Brahmasamstha – a mention that has been a major topic of debate in the Vedanta sub-schools of Hinduism.[53][59]

The Advaita Vedanta scholars state that this implicitly mentions the Sannyasa, whose goal is to get "knowledge, realization and thus firmly grounded in Brahman". Other scholars point to the structure of the verse and its explicit "three branches" declaration.[54] In other words, the fourth state of Brahmasamstha among men must have been known by the time this Chandogya verse was composed, but it is not certain whether a formal stage of Sannyasa life existed as a dharmic asrama at that time. Beyond chronological concerns, the verse has provided a foundation for Vedanta school's emphasis on ethics, education, simple living, social responsibility, and the ultimate goal of life as moksha through Brahman-knowledge.[51][54]

The discussion of ethics and moral conduct in man's life re-appears in other chapters of Chandogya Upanishad, such as in section 3.17.[60][61]

Third Prapāṭhaka

Brahman is the sun of all existence, Madhu Vidya

The Chandogya Upanishad presents the "Madhu Vidya" ("Honey Knowledge") in first eleven volumes of the third chapter.[62] Sun is praised as source of all light and life, and stated as worthy of meditation in a symbolic representation of Sun as "honey" of all Vedas.[63] The Brahman is stated in these volume of verses to be the sun of the Universe, and the 'natural sun' is a phenomenal manifestation of the Brahman.[64]

The simile of "honey" is extensively developed, with Vedas, the Itihasa and mythological stories, and the Upanishads are described as flowers.[64] The Rig hymns, the Yajur maxims, the Sama songs, the Atharva verses and deeper, secret doctrines of Upanishads are represented as the vehicles of rasa (nectar), that is the bees.[65] The nectar itself is described as "essence of knowledge, strength, vigor, health, renown, splendor".[66] The Sun is described as the honeycomb laden with glowing light of honey. The rising and setting of the Sun is likened to man's cyclic state of clarity and confusion, while the spiritual state of knowing Upanishadic insight of Brahman is described by Chandogya Upanishad as being one with Sun, a state of permanent day of perfect knowledge, the day which knows no night.[64]

Gayatri mantra: symbolism of all that is

Gayatri Mantra[67] is the symbol of the Brahman - the essence of everything, states volume 3.12 of the Chandogya Upanishad.[68] Gayatri as speech sings to everything and protects them, asserts the text.[68][69]

The Ultimate exists within oneself

The first six verses of the thirteenth volume of Chandogya's third chapter state a theory of Svarga (heaven) as human body, whose doorkeepers are eyes, ears, speech organs, mind and breath. To reach Svarga, asserts the text, understand these doorkeepers.[70] The Chandogya Upanishad then states that the ultimate heaven and highest world exists within oneself, as follows,

अथ यदतः परो दिवो ज्योतिर्दीप्यते विश्वतः पृष्ठेषु सर्वतः पृष्ठेष्वनुत्तमेषूत्तमेषु लोकेष्विदं वाव तद्यदिदमस्मिन्नन्तः पुरुषो ज्योतिस्तस्यैषा

Now that light which shines above this heaven, higher than all, higher than everything, in the highest world, beyond which there are no other worlds, that is the same light which is within man.

This premise, that the human body is the heaven world, and that Brahman (highest reality) is identical to the Atman (Self) within a human being is at the foundation of Vedanta philosophy.[70] The volume 3.13 of verses, goes on to offer proof in verse 3.13.8 that the highest reality is inside man, by stating that body is warm and this warmth must have an underlying hidden principle manifestation of the Brahman.[71] Max Muller states, that while this reasoning may appear weak and incomplete, but it shows that Vedic era human mind had transitioned from "revealed testimony" to "evidence-driven and reasoned knowledge".[71] This Brahman-Atman premise is more consciously and fully developed in section 3.14 of the Chandogya Upanishad.

Individual Self and the infinite Brahman is same, one's Self is God, Sandilya Vidya

The Upanishad presents the Śāṇḍilya doctrine in volume 14 of chapter 3.[73] This, states Paul Deussen,[74] is with Satapatha Brahmana 10.6.3, perhaps the oldest passage in which the basic premises of the Vedanta philosophy are fully expressed, namely – Atman (Self inside man) exists, the Brahman is identical with Atman, God is inside man.[75] The Chandogya Upanishad makes a series of statements in section 3.14 that have been frequently cited by later schools of Hinduism and modern studies on Indian philosophies.[73][75][76] These are,

Brahman, you see, is this whole world. With inner tranquillity, one should venerate it as Tajjalan (that from which he came forth, as that into which he will be dissolved, as that in which he breathes). Now, then, man is undoubtedly made of his Kratumaya (क्रतुमयः, resolve, will, purpose). What a man becomes on departing from here after death is in accordance with his (will, resolve) in this world. So he should make this resolve:

This elf (atman) of mine that lies deep within my heart — it is made of mind; the vital functions (prana) are its physical form; luminous is its appearance; the real is its intention; space is its essence (atman); it contains all actions, all desires, all smells, and all tastes; it has captured this whole world; it neither speaks nor pays any heed. This elf (atman) of mine that lies deep within my heart—it is smaller than a grain of rice or barley, smaller than a mustard seed, smaller even than a millet grain or a millet kernel; but it is larger than the Earth, larger than the intermediate region, larger than the sky, larger even than all these worlds put together. This Self (atman) of mine that lies deep within my heart—it contains all actions, all desires, all smells, and all tastes; it has captured this whole world; it neither speaks nor pays any heed. It is Brahman. On departing from here after death, I will become that. A man who has this resolve is never beset at all with doubts. This is what Shandilya used to say.

— Chandogya Upanishad 3.14.1 - 3.14.5[77]

The teachings in this section re-appear centuries later in the words of the 3rd century CE Neoplatonic Roman philosopher Plotinus in "Enneads 5.1.2".[74]

The Universe is an imperishable treasure chestedit

The Universe, states the Chandogya Upanishad in section 3.15, is a treasure-chest and the refuge for man.[78] This chest is where all wealth and everything rests states verse 3.15.1, and it is imperishable states verse 3.15.3.[79] The best refuge for man is this Universe and the Vedas, assert verses 3.15.4 through 3.15.7.[78][80] This section incorporates a benediction for the birth of a son.[79]

Life is a festival, ethics is one's donation to itedit

The section 3.17 of Chandogya Upanishad describes life as a celebration of a Soma-festival, whose dakshina (gifts, payment) is moral conduct and ethical precepts that includes non-violence, truthfulness, non-hypocrisy and charity unto others, as well as simple introspective life.[83] This is one of the earliest[84] statement of the Ahimsa principle as an ethical code of life, that later evolved to become the highest virtue in Hinduism.[85][86]

अथ यत्तपो दानमार्जवमहिँसा सत्यवचनमिति ता अस्य दक्षिणाः ॥ ४ ॥[87]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Chāndogya_Upaniṣad

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.Analytika

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk