A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Cairo

القاهرة | |

|---|---|

| Nickname: City of a Thousand Minarets | |

| Coordinates: 30°2′40″N 31°14′9″E / 30.04444°N 31.23583°E | |

| Country | Egypt |

| Governorate | Cairo |

| First major foundation | 641–642 AD (Fustat) |

| Last major foundation | 969 AD (Cairo) |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Khaled Abdel Aal[2] |

| Area | |

| • Metro | 2,734 km2 (1,056 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 23 m (75 ft) |

| Population (2018) | |

| • Capital city | 10,100,166[1] |

| • Metro | 22,183,000 |

| • Demonym | Cairene |

| GDP | |

| • Capital city | EGP 1,877 billion (US$ 120 billion) |

| • Metro | EGP 2,986 billion (US$ 190 billion) |

| Time zone | UTC+02:00 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+03:00 |

| Area code | (+20) 2 |

| Website | cairo.gov.eg |

| Official name | Historic Cairo |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, v, vi |

| Designated | 1979 |

| Reference no. | 89 |

Cairo (/ˈkaɪroʊ/ KY-roh; Arabic: القاهرة, romanized: al-Qāhirah)[6] is the capital of Egypt and the city-state Cairo Governorate, and is the country's largest city, home to 10 million people.[7] It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East, the Greater Cairo metropolitan area, which is the 12th-largest in the world by population with a population of over 22.1 million.[4]

Cairo is associated with ancient Egypt, as the Giza pyramid complex and the ancient cities of Memphis and Heliopolis are located in its geographical area. Located near the Nile Delta,[8][9] the city first developed as Fustat following the Muslim conquest of Egypt in 641 next to an existing ancient Roman fortress, Babylon. Cairo was founded by the Fatimid dynasty in 969. It later superseded Fustat as the main urban centre during the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods (12th–16th centuries).[10] Cairo has long been a centre of the region's political and cultural life, and is titled "the city of a thousand minarets" for its preponderance of Islamic architecture. Cairo's historic center was awarded World Heritage Site status in 1979.[11] Cairo is considered a World City with a "Beta +" classification according to GaWC.[12]

Cairo has the oldest and largest film and music industry in the Arab world, as well as Egypt's oldest institution of higher learning, Al-Azhar University. Many international media, businesses, and organizations have regional headquarters in the city; the Arab League has had its headquarters in Cairo for most of its existence.

With a population of over 10 million[13] spread over 453 km2 (175 sq mi), Cairo is by far the largest city in Egypt. An additional 9.5 million inhabitants live close to the city. Cairo, like many other megacities, suffers from high levels of pollution and traffic. The Cairo Metro, opened in 1987, is the oldest metro system in Africa,[14] and ranks amongst the fifteen busiest in the world,[15] with over 1 billion[16] annual passenger rides. The economy of Cairo was ranked first in the Middle East in 2005,[17] and 43rd globally on Foreign Policy's 2010 Global Cities Index.[18]

Etymology

The name of Cairo is derived from the Arabic al-Qāhirah (القاهرة), meaning 'the Vanquisher' or 'the Conqueror', given by the Fatimid Caliph al-Mu'izz following the establishment of the city as the capital of the Fatimid dynasty. Its full, formal name was al-Qāhirah al-Mu'izziyyah (القاهرة المعزيّة), meaning 'the Vanquisher of al-Mu'izz'.[19] It is also supposedly due to the fact that the planet Mars, known in Arabic by names such as an-Najm al-Qāhir (النجم القاهر, 'the Conquering Star'), was rising at the time of the city's founding.[20]

Egyptians often refer to Cairo as Maṣr (IPA: [mɑsˤɾ]; مَصر), the Egyptian Arabic name for Egypt itself, emphasizing the city's importance for the country.[21][22]

There are a number of Coptic names for the city. Tikešrōmi (Coptic: Ϯⲕⲉϣⲣⲱⲙⲓ Late Coptic: [di.kɑʃˈɾoːmi]) is attested in the 1211 text The Martyrdom of John of Phanijoit and is either a calque meaning 'man breaker' (Ϯ-, 'the', ⲕⲁϣ-, 'to break', and ⲣⲱⲙⲓ, 'man'), akin to Arabic al-Qāhirah, or a derivation from Arabic قَصْر الرُوم (qaṣr ar-rūm, "the Roman castle"), another name of Babylon Fortress in Old Cairo.[23] The Arabic name is also calqued as ⲧⲡⲟⲗⲓⲥ ϯⲣⲉϥϭⲣⲟ, "the victor city" in the Coptic antiphonary.[24]

The form Khairon (Coptic: ⲭⲁⲓⲣⲟⲛ) is attested in the modern Coptic text Ⲡⲓⲫⲓⲣⲓ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ϯⲁⲅⲓⲁ ⲙ̀ⲙⲏⲓ Ⲃⲉⲣⲏⲛⲁ (The Tale of Saint Verina).[25][better source needed] Lioui (Ⲗⲓⲟⲩⲓ Late Coptic: [lɪˈjuːj]) or Elioui (Ⲉⲗⲓⲟⲩⲓ Late Coptic: [ælˈjuːj]) is another name which is descended from the Greek name of Heliopolis (Ήλιούπολις).[23] Some argue that Mistram (Ⲙⲓⲥⲧⲣⲁⲙ Late Coptic: [ˈmɪs.təɾɑm]) or Nistram (Ⲛⲓⲥⲧⲣⲁⲙ Late Coptic: [ˈnɪs.təɾɑm]) is another Coptic name for Cairo, although others think that it is rather a name for the Abbasid province capital al-Askar.[26] Ⲕⲁϩⲓⲣⲏ (Kahi•ree) is a popular modern rendering of an Arabic name (others being Ⲕⲁⲓⲣⲟⲛ and Ⲕⲁϩⲓⲣⲁ ) which is modern folk etymology meaning 'land of sun'. Some argue that it was a name of an Egyptian settlement upon which Cairo was built, but it is rather doubtful as this name is not attested in any Hieroglyphic or Demotic source, although some researchers, like Paul Casanova, view it as a legitimate theory.[23] Cairo is also referred to as Ⲭⲏⲙⲓ (Late Coptic: [ˈkɪ.mi]) or Ⲅⲩⲡⲧⲟⲥ (Late Coptic: [ˈɡɪp.dos]), which means Egypt in Coptic, the same way it is referred to in Egyptian Arabic.[26]

Sometimes the city is informally referred to as Cairo by people from Alexandria (IPA: [ˈkæjɾo]; Egyptian Arabic: كايرو).[27]

History

Ancient settlements

The area around present-day Cairo had long been a focal point of Ancient Egypt due to its strategic location at the junction of the Nile Valley and the Nile Delta regions (roughly Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt), which also placed it at the crossing of major routes between North Africa and the Levant.[28][29] Memphis, the capital of Egypt during the Old Kingdom and a major city up until the Ptolemaic period, was located a short distance south west of present-day Cairo.[30] Heliopolis, another important city and major religious center, was located in what are now the modern districts of Matariya and Ain Shams in northeastern Cairo.[30][31] It was largely destroyed by the Persian invasions in 525 BC and 343 BC and partly abandoned by the late first century BC.[28]

However, the origins of modern Cairo are generally traced back to a series of settlements in the first millennium AD. Around the turn of the fourth century,[32] as Memphis was continuing to decline in importance,[33] the Romans established a large fortress along the east bank of the Nile. The fortress, called Babylon, was built by the Roman emperor Diocletian (r. 285–305) at the entrance of a canal connecting the Nile to the Red Sea that was created earlier by emperor Trajan (r. 98–117).[b][34] Further north of the fortress, near the present-day district of al-Azbakiya, was a port and fortified outpost known as Tendunyas (Coptic: ϯⲁⲛⲧⲱⲛⲓⲁⲥ)[35] or Umm Dunayn.[36][37][38] While no structures older than the 7th century have been preserved in the area aside from the Roman fortifications, historical evidence suggests that a sizeable city existed. The city was important enough that its bishop, Cyrus, participated in the Second Council of Ephesus in 449.[39]

The Byzantine-Sassanian War between 602 and 628 caused great hardship and likely caused much of the urban population to leave for the countryside, leaving the settlement partly deserted.[37] The site today remains at the nucleus of the Coptic Orthodox community, which separated from the Roman and Byzantine churches in the late 4th century. Cairo's oldest extant churches, such as the Church of Saint Barbara and the Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus (from the late 7th or early 8th century), are located inside the fortress walls in what is now known as Old Cairo or Coptic Cairo.[40]

Fustat and other early Islamic settlements

The Muslim conquest of Byzantine Egypt was led by Amr ibn al-As from 639 to 642. Babylon Fortress was besieged in September 640 and fell in April 641. In 641 or early 642, after the surrender of Alexandria (the Egyptian capital at the time), he founded a new settlement next to Babylon Fortress.[41][42] The city, known as Fustat (Arabic: الفسطاط, romanized: al-Fusṭāṭ, lit. 'the tent'), served as a garrison town and as the new administrative capital of Egypt. Historians such as Janet Abu-Lughod and André Raymond trace the genesis of present-day Cairo to the foundation of Fustat.[43][44] The choice of founding a new settlement at this inland location, instead of using the existing capital of Alexandria on the Mediterranean coast, may have been due to the new conquerors' strategic priorities. One of the first projects of the new Muslim administration was to clear and re-open Trajan's ancient canal in order to ship grain more directly from Egypt to Medina, the capital of the caliphate in Arabia.[45][46][47][48] Ibn al-As also founded a mosque for the city at the same time, now known as the Mosque of Amr Ibn al-As, the oldest mosque in Egypt and Africa (although the current structure dates from later expansions).[29][49][50][51]

In 750, following the overthrow of the Umayyad caliphate by the Abbasids, the new rulers created their own settlement to the northeast of Fustat which became the new provincial capital. This was known as al-Askar (Arabic: العسكر, lit. 'the camp') as it was laid out like a military camp. A governor's residence and a new mosque were also added, with the latter completed in 786.[52] The Red Sea canal re-excavated in the 7th century was closed by the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur in al-Mansur (r. 754–775),[53] but a part of the canal, known as the Khalij, continued to be a major feature of Cairo's geography and of its water supply until the 19th century.[54][29] In 861, on the orders of the Abbasid caliph al-Mutawakkil, a Nilometer was built on Roda Island near Fustat. Although it was repaired and given a new roof in later centuries, its basic structure is still preserved today, making it the oldest preserved Islamic-era structure in Cairo today.[55][56]

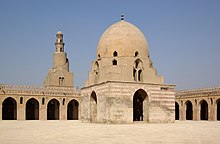

In 868 a commander of Turkic origin named Bakbak was sent to Egypt by the Abbasid caliph al-Mu'taz to restore order after a rebellion in the country. He was accompanied by his stepson, Ahmad ibn Tulun, who became effective governor of Egypt. Over time, Ibn Tulun gained an army and accumulated influence and wealth, allowing him to become the de facto independent ruler of both Egypt and Syria by 878.[57][58][59] In 870, he used his growing wealth to found a new administrative capital, al-Qata'i (Arabic: القطائـع, lit. 'the allotments'), to the northeast of Fustat and of al-Askar.[59][60] The new city included a palace known as the Dar al-Imara, a parade ground known as al-Maydan, a bimaristan (hospital), and an aqueduct to supply water. Between 876 and 879 Ibn Tulun built a great mosque, now known as the Mosque of Ibn Tulun, at the center of the city, next to the palace.[58][60] After his death in 884, Ibn Tulun was succeeded by his son and his descendants who continued a short-lived dynasty, the Tulunids. In 905, the Abbasids sent general Muhammad Sulayman al-Katib to re-assert direct control over the country. Tulunid rule was ended and al-Qatta'i was razed to the ground, except for the mosque which remains standing today.[61][62]

Foundation and expansion of Cairo

In 969, the Shi'a Isma'ili Fatimid empire conquered Egypt after ruling from Ifriqiya. The Fatimid general Jawhar Al Saqili founded a new fortified city northeast of Fustat and of former al-Qata'i. It took four years to build the city, initially known as al-Manṣūriyyah,[63] which was to serve as the new capital of the caliphate.[64] During that time, the construction of the al-Azhar Mosque was commissioned by order of the caliph, which developed into the third-oldest university in the world. Cairo would eventually become a centre of learning, with the library of Cairo containing hundreds of thousands of books.[65] When Caliph al-Mu'izz li Din Allah arrived from the old Fatimid capital of Mahdia in Tunisia in 973, he gave the city its present name, Qāhirat al-Mu'izz ("The Vanquisher of al-Mu'izz"),[63] from which the name "Cairo" (al-Qāhira) originates. The caliphs lived in a vast and lavish palace complex that occupied the heart of the city. Cairo remained a relatively exclusive royal city for most of this era, but during the tenure of Badr al-Gamali as vizier (1073–1094) the restrictions were loosened for the first time and richer families from Fustat were allowed to move into the city.[66] Between 1087 and 1092 Badr al-Gamali also rebuilt the city walls in stone and constructed the city gates of Bab al-Futuh, Bab al-Nasr, and Bab Zuweila that still stand today.[67]

During the Fatimid period Fustat reached its apogee in size and prosperity, acting as a center of craftsmanship and international trade and as the area's main port on the Nile.[68] Historical sources report that multi-story communal residences existed in the city, particularly in its center, which were typically inhabited by middle and lower-class residents. Some of these were as high as seven stories and could house some 200 to 350 people.[69] They may have been similar to Roman insulae and may have been the prototypes for the rental apartment complexes which became common in the later Mamluk and Ottoman periods.[69]

However, in 1168 the Fatimid vizier Shawar set fire to unfortified Fustat to prevent its potential capture by Amalric, the Crusader king of Jerusalem. While the fire did not destroy the city and it continued to exist afterward, it did mark the beginning of its decline. Over the following centuries it was Cairo, the former palace-city, that became the new economic center and attracted migration from Fustat.[70][71]

While the Crusaders did not capture the city in 1168, a continuing power struggle between Shawar, King Amalric, and the Zengid general Shirkuh led to the downfall of the Fatimid establishment.[72] In 1169, Shirkuh's nephew Saladin was appointed as the new vizier of Egypt by the Fatimids and two years later he seized power from the family of the last Fatimid caliph, al-'Āḍid.[73] As the first Sultan of Egypt, Saladin established the Ayyubid dynasty, based in Cairo, and aligned Egypt with the Sunni Abbasids, who were based in Baghdad.[74] In 1176, Saladin began construction on the Cairo Citadel, which was to serve as the seat of the Egyptian government until the mid-19th century. The construction of the Citadel definitively ended Fatimid-built Cairo's status as an exclusive palace-city and opened it up to common Egyptians and to foreign merchants, spurring its commercial development.[75] Along with the Citadel, Saladin also began the construction of a new 20-kilometre-long wall that would protect both Cairo and Fustat on their eastern side and connect them with the new Citadel. These construction projects continued beyond Saladin's lifetime and were completed under his Ayyubid successors.[76]

Apogee and decline under the Mamluks

In 1250, during the Seventh Crusade, the Ayyubid dynasty had a crisis with the death of al-Salih and power transitioned instead to the Mamluks, partly with the help of al-Salih's wife, Shajar ad-Durr, who ruled for a brief period around this time.[77][78] Mamluks were soldiers who were purchased as young slaves and raised to serve in the sultan's army. Between 1250 and 1517 the throne of the Mamluk Sultanate passed from one mamluk to another in a system of succession that was generally non-hereditary, but also frequently violent and chaotic.[79][80] The Mamluk Empire nonetheless became a major power in the region and was responsible for repelling the advance of the Mongols (most famously at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260) and for eliminating the last Crusader states in the Levant.[81]

Despite their military character, the Mamluks were also prolific builders and left a rich architectural legacy throughout Cairo.[82] Continuing a practice started by the Ayyubids, much of the land occupied by former Fatimid palaces was sold and replaced by newer buildings, becoming a prestigious site for the construction of Mamluk religious and funerary complexes.[83] Construction projects initiated by the Mamluks pushed the city outward while also bringing new infrastructure to the centre of the city.[84] Meanwhile, Cairo flourished as a centre of Islamic scholarship and a crossroads on the spice trade route among the civilisations in Afro-Eurasia.[85] Under the reign of the Mamluk sultan al-Nasir Muhammad (1293–1341, with interregnums), Cairo reached its apogee in terms of population and wealth.[86] By 1340, Cairo had a population of close to half a million, making it the largest city west of China.[85]

Multi-story buildings occupied by rental apartments, known as a rab' (plural ribā' or urbu), became common in the Mamluk period and continued to be a feature of the city's housing during the later Ottoman period.[87][88] These apartments were often laid out as multi-story duplexes or triplexes. They were sometimes attached to caravanserais, where the two lower floors were for commercial and storage purposes and the multiple stories above them were rented out to tenants. The oldest partially-preserved example of this type of structure is the Wikala of Amir Qawsun, built before 1341.[87][88] Residential buildings were in turn organized into close-knit neighbourhoods called a harat, which in many cases had gates that could be closed off at night or during disturbances.[88]

When the traveller Ibn Battuta first came to Cairo in 1326, he described it as the principal district of Egypt.[89] When he passed through the area again on his return journey in 1348 the Black Death was ravaging most major cities. He cited reports of thousands of deaths per day in Cairo.[90][91] Although Cairo avoided Europe's stagnation during the Late Middle Ages, it could not escape the Black Death, which struck the city more than fifty times between 1348 and 1517.[92] During its initial, and most deadly waves, approximately 200,000 people were killed by the plague,[93] and, by the 15th century, Cairo's population had been reduced to between 150,000 and 300,000.[94] The population decline was accompanied by a period of political instability between 1348 and 1412. It was nonetheless in this period that the largest Mamluk-era religious monument, the Madrasa-Mosque of Sultan Hasan, was built.[95] In the late 14th century the Burji Mamluks replaced the Bahri Mamluks as rulers of the Mamluk state, but the Mamluk system continued to decline.[96]

Though the plagues returned frequently throughout the 15th century, Cairo remained a major metropolis and its population recovered in part through rural migration.[96] More conscious efforts were conducted by rulers and city officials to redress the city's infrastructure and cleanliness. Its economy and politics also became more deeply connected with the wider Mediterranean.[96] Some Mamluk sultans in this period, such as Barbsay (r. 1422–1438) and Qaytbay (r. 1468–1496), had relatively long and successful reigns.[97] After al-Nasir Muhammad, Qaytbay was one of the most prolific patrons of art and architecture of the Mamluk era. He built or restored numerous monuments in Cairo, in addition to commissioning projects beyond Egypt.[98][99] The crisis of Mamluk power and of Cairo's economic role deepened after Qaytbay. The city's status was diminished after Vasco da Gama discovered a sea route around the Cape of Good Hope between 1497 and 1499, thereby allowing spice traders to avoid Cairo.[85]

Ottoman rule

Cairo's political influence diminished significantly after the Ottomans defeated Sultan al-Ghuri in the Battle of Marj Dabiq in 1516 and conquered Egypt in 1517. Ruling from Constantinople, Sultan Selim I relegated Egypt to a province, with Cairo as its capital.[100] For this reason, the history of Cairo during Ottoman times is often described as inconsequential, especially in comparison to other time periods.[85][101][102]

During the 16th and 17th centuries, Cairo still remained an important economic and cultural centre. Although no longer on the spice route, the city facilitated the transportation of Yemeni coffee and Indian textiles, primarily to Anatolia, North Africa, and the Balkans. Cairene merchants were instrumental in bringing goods to the barren Hejaz, especially during the annual hajj to Mecca.[101][103] It was during this same period that al-Azhar University reached the predominance among Islamic schools that it continues to hold today;[104][105] pilgrims on their way to hajj often attested to the superiority of the institution, which had become associated with Egypt's body of Islamic scholars.[106] The first printing press of the Middle East, printing in Hebrew, was established in Cairo c. 1557 by a scion of the Soncino family of printers, Italian Jews of Ashkenazi origin who operated a press in Constantinople. The existence of the press is known solely from two fragments discovered in the Cairo Geniza.[107]

Under the Ottomans, Cairo expanded south and west from its nucleus around the Citadel.[108] The city was the second-largest in the empire, behind Constantinople, and, although migration was not the primary source of Cairo's growth, twenty percent of its population at the end of the 18th century consisted of religious minorities and foreigners from around the Mediterranean.[109] Still, when Napoleon arrived in Cairo in 1798, the city's population was less than 300,000, forty percent lower than it was at the height of Mamluk—and Cairene—influence in the mid-14th century.[85][109]

The French occupation was short-lived as British and Ottoman forces, including a sizeable Albanian contingent, recaptured the country in 1801. Cairo itself was besieged by a British and Ottoman force culminating with the French surrender on 22 June 1801.[110] The British vacated Egypt two years later, leaving the Ottomans, the Albanians, and the long-weakened Mamluks jostling for control of the country.[111][112] Continued civil war allowed an Albanian named Muhammad Ali Pasha to ascend to the role of commander and eventually, with the approval of the religious establishment, viceroy of Egypt in 1805.[113]

Modern era

Until his death in 1848, Muhammad Ali Pasha instituted a number of social and economic reforms that earned him the title of founder of modern Egypt.[114][115] However, while Muhammad Ali initiated the construction of public buildings in the city,[116] those reforms had minimal effect on Cairo's landscape.[117] Bigger changes came to Cairo under Isma'il Pasha (r. 1863–1879), who continued the modernisation processes started by his grandfather.[118] Drawing inspiration from Paris, Isma'il envisioned a city of maidans and wide avenues; due to financial constraints, only some of them, in the area now composing Downtown Cairo, came to fruition.[119] Isma'il also sought to modernize the city, which was merging with neighbouring settlements, by establishing a public works ministry, bringing gas and lighting to the city, and opening a theatre and opera house.[120][121]

The immense debt resulting from Isma'il's projects provided a pretext for increasing European control, which culminated with the British invasion in 1882.[85] The city's economic centre quickly moved west toward the Nile, away from the historic Islamic Cairo section and toward the contemporary, European-style areas built by Isma'il.[122][123] Europeans accounted for five percent of Cairo's population at the end of the 19th century, by which point they held most top governmental positions.[124]

In 1906 the Heliopolis Oasis Company headed by the Belgian industrialist Édouard Empain and his Egyptian counterpart Boghos Nubar, built a suburb called Heliopolis (city of the sun in Greek) ten kilometers from the center of Cairo.[125][126] In 1905–1907 the northern part of the Gezira island was developed by the Baehler Company into Zamalek, which would later become Cairo's upscale "chic" neighbourhood.[127] In 1906 construction began on Garden City, a neighbourhood of urban villas with gardens and curved streets.[127]

The British occupation was intended to be temporary, but it lasted well into the 20th century. Nationalists staged large-scale demonstrations in Cairo in 1919,[85] five years after Egypt had been declared a British protectorate.[128] Nevertheless, this led to Egypt's independence in 1922.

The King Fuad I Edition of the Qur'an[129] was first published on 10 July 1924 in Cairo under the patronage of King Fuad.[130][131] The goal of the government of the newly formed Kingdom of Egypt was not to delegitimize the other variant Quranic texts ("qira'at"), but to eliminate errors found in Qur'anic texts used in state schools. A committee of teachers chose to preserve a single one of the canonical qira'at "readings", namely that of the "Ḥafṣ" version,[132] an 8th-century Kufic recitation. This edition has become the standard for modern printings of the Quran[133][134] for much of the Islamic world.[135] The publication has been called a "terrific success", and the edition has been described as one "now widely seen as the official text of the Qur'an", so popular among both Sunni and Shi'a that the common belief among less well-informed Muslims is "that the Qur'an has a single, unambiguous reading". Minor amendments were made later in 1924 and in 1936 - the "Faruq edition" in honour of then ruler, King Faruq.[136]

British occupation until 1956

British troops remained in the country until 1956. During this time, urban Cairo, spurred by new bridges and transport links, continued to expand to include the upscale neighbourhoods of Garden City, Zamalek, and Heliopolis.[137] Between 1882 and 1937, the population of Cairo more than tripled—from 347,000 to 1.3 million[138]—and its area increased from 10 to 163 km2 (4 to 63 sq mi).[139]

The city was devastated during the 1952 riots known as the Cairo Fire or Black Saturday, which saw the destruction of nearly 700 shops, movie theatres, casinos and hotels in downtown Cairo.[140] The British departed Cairo following the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, but the city's rapid growth showed no signs of abating. Seeking to accommodate the increasing population, President Gamal Abdel Nasser redeveloped Tahrir Square and the Nile Corniche, and improved the city's network of bridges and highways.[141] Meanwhile, additional controls of the Nile fostered development within Gezira Island and along the city's waterfront. The metropolis began to encroach on the fertile Nile Delta, prompting the government to build desert satellite towns and devise incentives for city-dwellers to move to them.[142]

After 1956

In the second half of the 20th century Cairo continue to grow enormously in both population and area. Between 1947 and 2006 the population of Greater Cairo went from 2,986,280 to 16,292,269.[143] The population explosion also drove the rise of "informal" housing ('ashwa'iyyat), meaning housing that was built without any official planning or control.[144] The exact form of this type of housing varies considerably but usually has a much higher population density than formal housing. By 2009, over 63% of the population of Greater Cairo lived in informal neighbourhoods, even though these occupied only 17% of the total area of Greater Cairo.[145] According to economist David Sims, informal housing has the benefits of providing affordable accommodation and vibrant communities to huge numbers of Cairo's working classes, but it also suffers from government neglect, a relative lack of services, and overcrowding.[146]

The "formal" city was also expanded. The most notable example was the creation of Madinat Nasr, a huge government-sponsored expansion of the city to the east which officially began in 1959 but was primarily developed in the mid-1970s.[147] Starting in 1977 the Egyptian government established the New Urban Communities Authority to initiate and direct the development of new planned cities on the outskirts of Cairo, generally established on desert land.[148][149][150] These new satellite cities were intended to provide housing, investment, and employment opportunities for the region's growing population as well as to pre-empt the further growth of informal neighbourhoods.[148] As of 2014, about 10% of the population of Greater Cairo lived in the new cities.[148]

Concurrently, Cairo established itself as a political and economic hub for North Africa and the Arab world, with many multinational businesses and organisations, including the Arab League, operating out of the city. In 1979 the historic districts of Cairo were listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[11]

In 1992, Cairo was hit by an earthquake causing 545 deaths, injuring 6,512 and leaving around 50,000 people homeless.[151]

2011 Egyptian revolution

Cairo's Tahrir Square was the focal point of the 2011 Egyptian revolution against former president Hosni Mubarak.[152] Over 2 million protesters were at Cairo's Tahrir square. More than 50,000 protesters first occupied the square on 25 January, during which the area's wireless services were reported to be impaired.[153] In the following days Tahrir Square continued to be the primary destination for protests in Cairo[154] as it took place following a popular uprising that began on Tuesday, 25 January 2011 and continued until June 2013. The uprising was mainly a campaign of non-violent civil resistance, which featured a series of demonstrations, marches, acts of civil disobedience, and labour strikes. Millions of protesters from a variety of socio-economic and religious backgrounds demanded the overthrow of the regime of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak. Despite being predominantly peaceful in nature, the revolution was not without violent clashes between security forces and protesters, with at least 846 people killed and 6,000 injured. The uprising took place in Cairo, Alexandria, and in other cities in Egypt, following the Tunisian revolution that resulted in the overthrow of the long-time Tunisian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.[155] On 11 February, following weeks of determined popular protest and pressure, Hosni Mubarak resigned from office.

Post-revolutionary Cairo

Under the rule of President el-Sisi, in March 2015 plans were announced for another yet-unnamed planned city to be built further east of the existing satellite city of New Cairo, intended to serve as the new capital of Egypt.[156]

Geography

Cairo is located in northern Egypt, known as Lower Egypt, 165 km (100 mi) south of the Mediterranean Sea and 120 km (75 mi) west of the Gulf of Suez and Suez Canal.[157] The city lies along the Nile River, immediately south of the point where the river leaves its desert-bound valley and branches into the low-lying Nile Delta region. Although the Cairo metropolis extends away from the Nile in all directions, the city of Cairo resides only on the east bank of the river and two islands within it on a total area of 453 km2 (175 sq mi).[158][159] Geologically, Cairo lies on alluvium and sand dunes which date from the quaternary period.[160][161]

Until the mid-19th century, when the river was tamed by dams, levees, and other controls, the Nile in the vicinity of Cairo was highly susceptible to changes in course and surface level. Over the years, the Nile gradually shifted westward, providing the site between the eastern edge of the river and the Mokattam highlands on which the city now stands. The land on which Cairo was established in 969 (present-day Islamic Cairo) was located underwater just over three hundred years earlier, when Fustat was first built.[162]

Low periods of the Nile during the 11th century continued to add to the landscape of Cairo; a new island, known as Geziret al-Fil, first appeared in 1174, but eventually became connected to the mainland. Today, the site of Geziret al-Fil is occupied by the Shubra district. The low periods created another island at the turn of the 14th century that now composes Zamalek and Gezira. Land reclamation efforts by the Mamluks and Ottomans further contributed to expansion on the east bank of the river.[163]

Because of the Nile's movement, the newer parts of the city—Garden City, Downtown Cairo, and Zamalek—are located closest to the riverbank.[164] The areas, which are home to most of Cairo's embassies, are surrounded on the north, east, and south by the older parts of the city. Old Cairo, located south of the centre, holds the remnants of Fustat and the heart of Egypt's Coptic Christian community, Coptic Cairo. The Boulaq district, which lies in the northern part of the city, was born out of a major 16th-century port and is now a major industrial centre. The Citadel is located east of the city centre around Islamic Cairo, which dates back to the Fatimid era and the foundation of Cairo. While western Cairo is dominated by wide boulevards, open spaces, and modern architecture of European influence, the eastern half, having grown haphazardly over the centuries, is dominated by small lanes, crowded tenements, and Islamic architecture.

Northern and extreme eastern parts of Cairo, which include satellite towns, are among the most recent additions to the city, as they developed in the late-20th and early-21st centuries to accommodate the city's rapid growth. The western bank of the Nile is commonly included within the urban area of Cairo, but it composes the city of Giza and the Giza Governorate. Giza city has also undergone significant expansion over recent years, and today has a population of 2.7 million.[159] The Cairo Governorate was just north of the Helwan Governorate from 2008 when some Cairo's southern districts, including Maadi and New Cairo, were split off and annexed into the new governorate,[165] to 2011 when the Helwan Governorate was reincorporated into the Cairo Governorate.

According to the World Health Organization, the level of air pollution in Cairo is nearly 12 times higher than the recommended safety level.[166]

Climate

In Cairo, and along the Nile River Valley, the climate is a hot desert climate (BWh according to the Köppen climate classification system[167]).

Wind storms can be frequent, bringing Saharan dust into the city, from March to May and the air often becomes uncomfortably dry. Winters are mild to warm, while summers are long and hot. High temperatures in winter range from 14 to 22 °C (57 to 72 °F), while night-time lows drop to below 11 °C (52 °F), often to 5 °C (41 °F). In summer, the highs often exceed 31 °C (88 °F) but rarely surpass 40 °C (104 °F), and lows drop to about 20 °C (68 °F). Rainfall is sparse and only happens in the colder months, but sudden showers can cause severe flooding. The summer months have high humidity due to its coastal location. Snowfall is extremely rare; a small amount of graupel, widely believed to be snow, fell on Cairo's easternmost suburbs on 13 December 2013, the first time Cairo's area received this kind of precipitation in many decades.[168] Dew points in the hottest months range from 13.9 °C (57 °F) in June to 18.3 °C (65 °F) in August.[169]

| Climate data for Cairo (Cairo International Airport) 1991–2020 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 31.0 (87.8) |

34.2 (93.6) |

37.9 (100.2) |

43.2 (109.8) |

47.8 (118.0) |

46.4 (115.5) |

42.6 (108.7) |

43.4 (110.1) |

43.7 (110.7) |

41.0 (105.8) |

37.4 (99.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

47.8 (118.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 18.9 (66.0) |

20.5 (68.9) |

23.8 (74.8) |

28.1 (82.6) |

32.2 (90.0) |

34.6 (94.3) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.9 (94.8) |

33.4 (92.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

24.9 (76.8) |

20.5 (68.9) |

28.1 (82.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 14.4 (57.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

18.3 (64.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

28.2 (82.8) |

29.1 (84.4) |

29.2 (84.6) Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Cairo,_Egypt Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Analytika

Antropológia Aplikované vedy Bibliometria Dejiny vedy Encyklopédie Filozofia vedy Forenzné vedy Humanitné vedy Knižničná veda Kryogenika Kryptológia Kulturológia Literárna veda Medzidisciplinárne oblasti Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy Metavedy Metodika Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk | |||||