A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Battle of Navarino | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Greek War of Independence | |||||||

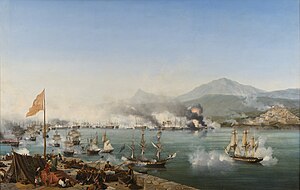

The Naval Battle of Navarino, Ambroise Louis Garneray | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

(OOB) 1,252 guns8,000 crewmen[1] |

3 ships of the line 17 frigates 30 corvettes 5 schooners 28 brigs 5-6 fireships (OOB) 2,158 guns 20,000 crewmen[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

181 killed 480 wounded |

4,000 killed or wounded 4,000 captured 55 ships lost[1] | ||||||

Location within Peloponnese | |||||||

The Battle of Navarino was a naval battle fought on 20 October (O. S. 8 October) 1827, during the Greek War of Independence (1821–29), in Navarino Bay (modern Pylos), on the west coast of the Peloponnese peninsula, in the Ionian Sea. Allied forces from Britain, France, and Russia decisively defeated Ottoman and Egyptian forces which were trying to suppress the Greeks, thereby making Greek independence much more likely. An Ottoman armada which, in addition to Imperial warships, included squadrons from the eyalets of Egypt and Tunis,[a] was destroyed by an Allied force of British, French and Russian warships. It was the last major naval battle in history to be fought entirely with sailing ships, although most ships fought at anchor. The Allies' victory was achieved through superior firepower and gunnery.

The context of the three Great Powers' intervention in the Greek conflict was the Russian Empire's long-running expansion at the expense of the decaying Ottoman Empire. Russia's ambitions in the region were seen as a major geostrategic threat by the other European powers, which feared the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of Russian hegemony in the Eastern Mediterranean. The precipitating factor was support of elements in Orthodox Russia for Greek coreligionists, despite the opposition of Tsar Alexander in 1821 following the Greek rebellion against their Ottoman overlords. Similarly, despite official British interest in maintaining the Ottoman Empire, British public opinion strongly supported the Greeks. Fearing unilateral Russian action, Britain and France bound Russia, by treaty, to a joint intervention which aimed to secure Greek autonomy, whilst still preserving Ottoman territorial integrity as a check on Russia.

The Powers agreed, by the Treaty of London (1827), to force the Ottoman government to grant the Greeks autonomy within the empire and despatched naval squadrons to the Eastern Mediterranean to enforce their policy. The naval battle happened more by accident than by design as a result of a manoeuvre by the Allied commander-in-chief, Admiral Edward Codrington, aimed at coercing the Ottoman commander to obey Allied instructions. The sinking of the Ottomans' Mediterranean fleet saved the fledgling Greek Republic from collapse. But it required two more military interventions by Russia, in the form of the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–9 and a French expeditionary force to the Peloponnese to force the withdrawal of Ottoman forces from Central and Southern Greece, to finally secure Greek independence.

Background

The Ottoman Turks had conquered the Greek-controlled Byzantine empire during the 15th century, taking over its territory and its capital, Constantinople, and becoming its effective successor-state.[3] In 1821, Greek nationalists revolted against the Ottomans, aiming to liberate ethnic Greeks from four centuries of Ottoman rule.[4] Fighting raged for several years but by 1825, a stalemate had developed, with the Greeks unable to drive the Ottomans out of most of Greece, but the Ottomans were unable to crush the revolt definitively. However, in 1825, the Sultan succeeded in breaking the stalemate. He persuaded his powerful wali (viceroy) of Egypt, Muhammad Ali Pasha, who was technically his vassal but in practice autonomous, to deploy his Western-trained and equipped army and navy against the Greeks. In return, the Sultan promised to grant the rebel heartland, the Peloponnese, as a hereditary fief to Ali's eldest son, Ibrahim. In February 1825, Ibrahim led an expeditionary force of 16,000 into the Peloponnese, and soon overran its western part; he failed, however, to take the eastern section, where the rebel government was based (at Nafplion).[5]

The Greek revolutionaries remained defiant, and appointed experienced philhellenic British officers at the head of the army and fleet: Maj Sir Richard Church (land) and Lord Cochrane (sea). By this time however, the Greek provisional government's land and sea forces were far inferior to those of the Ottomans and Egyptians: in 1827, Greek regular troops numbered less than 5,000, compared to 25,000 Ottomans in central Greece and 15,000 Egyptians in the Peloponnese. Also, the Greek government was virtually bankrupt. Many of the key fortresses on what little territory it controlled were in Ottoman hands. It seemed only a matter of time before the Greeks were forced to capitulate.[6] At this critical juncture, the Greek cause was rescued by the decision of three Great Powers—Great Britain, France and Russia—to intervene jointly in the conflict.

Diplomacy of the Great Powers

From the inception of the Greek revolt until 1826, Anglo-Austrian diplomatic efforts were aimed at ensuring the non-intervention of the other great powers in the conflict.[7] Their objective was to stall Russian military intervention in support of the Greeks, in order to give the Ottomans time to defeat the rebellion.[8] However, the Ottomans proved unable to suppress the revolt during the long period of non-intervention secured by Anglo-Austrian diplomacy. By the time the Ottomans were making serious progress, the situation evolved in ways that would make non-interventionism untenable. In December 1825, the diplomatic landscape changed with the death of Tsar Alexander and the succession of his younger brother Nicholas I to the Russian throne. Nicholas was a more decisive and risk-taking character than his brother, as well as being far more nationalistic. The British government's response to the evolving situation was to move towards joint intervention instead to limit Russian expansionism. Britain, France, and Russia signed the Treaty of London on 6 July 1827. The treaty called for an immediate armistice between the belligerents, in effect demanding a cessation of Ottoman military operations in Greece just when the Ottomans had victory in their grasp. It also offered Allied mediation in the negotiations on a final settlement that were to follow the armistice.[9] The treaty called on the Ottomans to grant Greece a degree of autonomy, but envisaged it ultimately remaining under Ottoman suzerainty.[10]

A secret clause in the agreement provided that if the Ottomans failed to accept the armistice within a month, each signatory Power would despatch a consul to Nafplion, the capital of the Hellenic Republic, thereby granting de facto recognition to the rebel government, something no Power had done hitherto.[11] The same clause authorized the signatories in concert to instruct their naval commanders in the Mediterranean to "take all measures that circumstances may suggest" (i.e. including military action) to enforce the Allied demands, if the Ottomans failed to comply within the specified time limit. However, the clause added that Allied commanders should not take sides in the conflict.[12] On 20 August 1827, the British naval commander-in-chief in the Mediterranean, Vice-Admiral of the Blue Sir Edward Codrington, a veteran of 44 years at sea and a popular hero for his role in the Battle of Trafalgar, received his government's instructions regarding enforcement of the treaty. Codrington could not have been a less suitable person for a task which required great tact. An impetuous fighting sailor, he entirely lacked diplomatic finesse, a quality he despised and derisively ascribed to his French counterpart, Henri de Rigny. He was also a sympathiser with the Greek cause, having subscribed to the London Philhellenic Committee.[13]

Order of battle

Exact figures for the Ottoman/Egyptian fleet are difficult to establish. The figures given above are mainly those enclosed by Codrington in his report. These were obtained by one of his officers from the French secretary of the Ottoman fleet, a M. Letellier. However, another report by Letellier to the British ambassador to the Ottomans gives two more frigates and 20 fewer corvettes/brigs for a total of 60 warships. James assesses the Ottomans' "effective" strength as even lower: three ships of the line, 15 large frigates and 18 corvettes, totaling just 36 ships.[14]

Ships

| British squadron (Vice Admiral Edward Codrington) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ship | Rate | Guns | Navy | Commander | Casualties | Notes | ||||

| Killed | Wounded | Total | ||||||||

| Asia | Second-rate | 84 | Captain Edward Curzon ; commander Robert Lambert Baynes | 18 | 67 | 85 | Flagship of the British squadron, flagship of the Allied fleet. | |||

| Genoa | Third-rate | 76 | Captain Walter Bathurst ; commander Richard Dickenson | 26 | 33 | 59 | ||||

| Albion | Third-rate | 74 | Captain John Acworth Ommanney ; commander John Norman Campbell | 10 | 50 | 60 | ||||

| Glasgow | Fifth-rate | 50 | Captain Hon. James Ashley Maude | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Cambrian | Fifth-rate | 48 | Captain Gawen William Hamilton, C.B. | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Dartmouth | Fifth-rate | 42 | Captain Thomas Fellowes, C.B. | 6 | 8 | 14 | ||||

| Talbot | Sixth-rate | 28 | Captain Hon. Frederick Spencer | 6 | 17 | 23 | ||||

| HMS Rose | Sloop | 18 | Commander Lewis Davies | 3 | 15 | 18 | ||||

| HMS Brisk | Brig-sloop | 10 | Commander Hon. William Anson | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| HMS Musquito | Brig-sloop | 10 | Commander George Bohun Martin | 2 | 4 | 6 | ||||

| HMS Philomel | Brig-sloop | 10 | Commander Henry Chetwynd-Talbot | 1 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| HMS Hind | Cutter | 10 | ||||||||

| French squadron (Rear Admiral Henri de Rigny) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ship | Rate | Guns | Navy | Commander | Casualties | Notes | ||||

| Killed | Wounded | Total | ||||||||

| Breslaw | Second-rate | 84 | Captain Botherel de La Bretonnière | 1 | 14 | 15 | ||||

| Scipion | Third-rate | 80 | Captain Pierre Bernard Milius | 2 | 36 | 38 | ||||

| Trident | Third-rate | 74 | Captain Morice | 0 | 7 | 7 | ||||

| Sirène | First-rank frigate | 60 | Contre-amiral Henri de Rigny, Captain Robert | 2 | 42 | 44 | Flagship of the French squadron. | |||

| Armide | Second-rank frigate | 44 | Captain Hugon | 14 | 29 | 43 | ||||

| Alcyone | Schooner | 10 to 16 | Captain Turpin | 1 | 9 | 10 | ||||

| Daphné | Schooner | 6 | Captain Frézier | 1 | 5 | 6 | ||||

| Russian squadron (Rear Admiral Lodewijk van Heiden) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ship | Rate | Guns | Navy | Commander | Casualties | Notes | ||||

| Killed | Wounded | Total | ||||||||

| Gangut | Second-rate | 84 | Captain Alexander Pavlovich Avinov | 14 | 37 | 51 | Lieutenant Pyotr Anjou distinguished himself during the battle. | |||

| Azov | Third-rate | 80 | Captain Mikhail Lazarev | 24 | 67 | 91 | Flagship of the Russian squadron. | |||

| Iezekiil' | Third-rate | 80 | Captain Svinkin | 13 | 18 | 31 | ||||

| Aleksandr Nevskii | Third-rate | 80 | Captain Bogdanovich | 5 | 7 | 12 | ||||

| Provornyi | Fifth-rate | 48 | Captain Yepanchin | 3 | 4 | 7 | ||||

| Konstantin | Fifth-rate | 44 | Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Analytika

Antropológia Aplikované vedy Bibliometria Dejiny vedy Encyklopédie Filozofia vedy Forenzné vedy Humanitné vedy Knižničná veda Kryogenika Kryptológia Kulturológia Literárna veda Medzidisciplinárne oblasti Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy Metavedy Metodika Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk | |||||||