A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| 2011 Bahraini uprising | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab Spring, Iran–Saudi Arabia proxy conflict, and the insurgency in Bahrain | |||

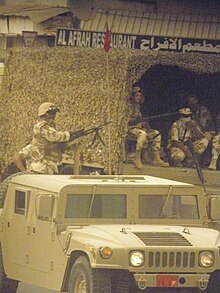

Clockwise from top-left: Protesters raising their hands towards the Pearl Roundabout on 19 February 2011; Teargas usage by security forces and clashes with protesters on 13 March; Over 100,000 Bahrainis taking part in the "March of loyalty to martyrs", on 22 February; clashes between security forces and protesters on 13 March; Bahraini armed forces blocking an entrance to a Bahraini village. | |||

| Date | 14 February – 18 March 2011 (1 month and 4 days) (occasional demonstrations since 2011) | ||

| Location | Bahrain 26°01′39″N 50°33′00″E / 26.02750°N 50.55000°E | ||

| Caused by |

| ||

| Goals |

| ||

| Methods | |||

| Status |

| ||

| Concessions |

| ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

Leaders of Bahrain opposition parties 8

Human rights defenders 2

Independent opposition leaders 1

8

2

| |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

| |||

The 2011 Bahraini uprising was a series of anti-government protests in Bahrain led by the Shia-dominant and some Sunni minority Bahraini opposition from 2011 until 2014. The protests were inspired by the unrest of the 2011 Arab Spring and protests in Tunisia and Egypt and escalated to daily clashes after the Bahraini government repressed the revolt with the support of the Gulf Cooperation Council and Peninsula Shield Force.[25] The Bahraini protests were a series of demonstrations, amounting to a sustained campaign of non-violent civil disobedience[26] and some violent[27] resistance in the Persian Gulf country of Bahrain.[28] As part of the revolutionary wave of protests in the Middle East and North Africa following the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia, the Bahraini protests were initially aimed at achieving greater political freedom and equality for the 70% Shia population.[29][30]

This expanded to a call to end the monarchy of Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa[4] following a deadly night raid on 17 February 2011 against protesters at the Pearl Roundabout in the capital Manama,[31][32] known locally as Bloody Thursday. Protesters in Manama camped for days at the Pearl Roundabout, which became the centre of the protests. After a month, the government of Bahrain requested troops and police aid from the Gulf Cooperation Council. On 14 March, 1,000 troops from Saudi Arabia, 500 troops from UAE and naval ships from Kuwait entered Bahrain and crushed the uprising.[33] A day later, King Hamad declared martial law and a three-month state of emergency.[34][35] Pearl Roundabout was cleared of protesters and the iconic statue at its center was demolished.[36]

Occasional demonstrations have continued since. After the state of emergency was lifted on 1 June 2011, the opposition party, Al Wefaq National Islamic Society, organized several weekly protests[37] usually attended by tens of thousands.[38] On 9 March 2012, over 100,000 attended[39] and another on 31 August attracted tens of thousands.[40] Daily smaller-scale protests and clashes continued, mostly outside Manama's business districts.[41][42] By April 2012, more than 80 had died.[43] The police response was described as a "brutal" crackdown on "peaceful and unarmed" protesters, including doctors and bloggers.[44][45][46] The police carried out midnight house raids in Shia neighbourhoods, beatings at checkpoints and denial of medical care in a campaign of intimidation.[47][48][49] More than 2,929 people have been arrested,[50][51] and at least five died due to torture in police custody.[10]: 287–288

In early July 2013, Bahraini activists called for major rallies on 14 August under the title Bahrain Tamarod.[52]

Naming

The Bahraini uprising is also known as the 14 February uprising[53] and Pearl uprising.[54]

Background

The roots of the uprising date back to the beginning of the 20th century. Bahrainis have protested sporadically throughout the last decades demanding social, economic and political rights.[10]: 162 Demonstrations were present as early as the 1920s and the first municipal elections to fill half the seats on local councils was held in 1926.[55]

History

The country has been ruled by the House of Khalifa since the Bani Utbah invasion of Bahrain in 1783, and was a British protectorate for most of the 20th century. In 1926, Charles Belgrave, a British national operating as an adviser to the ruler, became the de facto ruler and oversaw the transition to a "modern" state.[56] The National Union Committee (NUC) formed in 1954 was the earliest serious challenge to the status quo.[57] Two year after its formation, NUC leaders were imprisoned and deported by authorities.

In 1965, the one-month March Intifada uprising by oil workers was crushed. The following year a new British adviser was appointed, Ian Henderson, who was known for allegedly ordering torture and assassinations in Kenya. He was tasked with heading and developing the General Directorate for State Security Investigations.[56]

In 1971, Bahrain became an independent state, and in 1973 the country held its first parliamentary election. However, only two years after the end of British rule, the constitution was suspended and the assembly dissolved by Isa bin Salman Al Khalifa, the Emir at the time.[56] Human rights deteriorated in the period between 1975 and 2001, accompanied by increased repression. The 1981 Bahraini coup d'état attempt failed.

In 1992, 280 society leaders demanded the return of the parliament and constitution, which the government rejected.[58] Two years later the 1990s uprising in Bahrain began. Throughout the uprising large demonstrations and multiple acts of violence occurred. Over forty people were killed, including several detainees whilst in police custody, and at least three policemen.[56][58]

In 1999, Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa succeeded his father. He successfully ended the uprising in 2001 after introducing the wide-ranging National Action Charter of Bahrain reforms, which 98.4 percent of Bahrainis voted in favour of in a nationwide referendum. The following year, Bahraini opposition "felt betrayed" after the government issued a unilateral new constitution. Despite earlier promises, the appointed Consultative Council, the upper house, of the National Assembly of Bahrain, was given more powers than the elected Council of Representatives, the lower house.[55] The Emir became a king with wide executive authority.[10]: 15

Four opposition parties boycotted the 2002 parliamentary election, however in the 2006 election one of them, Al Wefaq, won a plurality.[59] The participation in elections increased the split between opposition associations. The Haq Movement was founded and utilized street protests to seek change instead of bringing change within the parliament.[55]

The period between 2007 and 2010 saw sporadic protests which were followed by large arrests.[60] Since then, tensions have increased "dangerously".[61]

Human rights

The state of human rights in Bahrain was criticized in the period between 1975 and 2001. The government had committed wide range violations including systematic torture.[62][63] Following reforms in 2001, human rights improved significantly[64] and were praised by Amnesty International.[65] They allegedly began deteriorating again at the end of 2007 when torture and repression tactics were being used again.[60] By 2010, torture had become common and Bahrain's human rights record was described as "dismal" by Human Rights Watch.[66] The Shia majority have long complained of what they call systemic discrimination.[67] They accuse the government of naturalizing Sunnis from neighbouring countries[68] and gerrymandering electoral districts.[69]

In 2006, the Al Bandar report revealed a political conspiracy by government officials in Bahrain to foment sectarian strife and marginalize the majority Shia community in the country.

Economy

Bahrain is relatively poor when compared to its oil-rich Persian Gulf neighbours; its oil has "virtually dried up"[68] and it depends on international banking and the tourism sector.[70] Bahrain's unemployment rate is among the highest in the region.[71] Extreme poverty does not exist in Bahrain where the average daily income is US$12.8; however, 11 percent of citizens suffer from relative poverty.[72]

Foreign relations

Bahrain hosts the United States Naval Support Activity Bahrain, the home of the US Fifth Fleet; the US Department of Defense considers the location critical to its attempts to counter Iranian military power in the region.[68] The Saudi Arabian government and other Gulf region governments strongly support the King of Bahrain.[68][73] Although government officials and media often accuse the opposition of being influenced by Iran, a government-appointed commission found no evidence supporting the claim.[74] Iran has historically claimed Bahrain as a province,[75] but the claim was dropped after a United Nations survey in 1970 found that most Bahraini people preferred independence over Iranian control.[76]

Lead-up to the protests

Inspired by the successful uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia,[77] opposition activists starting from January 2011 filled the social media websites Facebook and Twitter as well as online forums, e-mails and text messages with calls to stage major pro-democracy protests.[10]: 65 [67][78] Bahraini youths described their plans as an appeal for Bahrainis "to take to the streets on Monday 14 February in a peaceful and orderly manner in order to rewrite the constitution and to establish a body with a full popular mandate".[79]

The day had a symbolic value[67] as it was the tenth anniversary of a referendum in favor of the National Action Charter and the ninth anniversary of the Constitution of 2002.[10]: 67 [68] Unregistered opposition parties such as the Haq Movement and Bahrain Freedom Movement supported the plans, while the National Democratic Action Society only announced its support for "the principle of the right of the youth to demonstrate peacefully" one day before the protests. Other opposition groups including Al Wefaq, Bahrain's main opposition party, did not explicitly call for or support protests; however its leader Ali Salman demanded political reforms.[10]: 66

A few weeks before the protests, the government made a number of concessions such as offering to free some of the children arrested in the August crackdown and increased social spending.[80] On 4 February, several hundred Bahrainis gathered in front of the Egyptian embassy in Manama to express solidarity with anti-government protesters there.[81] On 11 February, at the Khutbah preceding Friday prayer, Shiekh Isa Qassim said "the winds of change in the Arab world unstoppable". He demanded to end torture and discrimination, release political activists and rewrite the constitution.[10]: 67 Appearing on the state media, King Hamad announced that each family will be given 1,000 Bahraini dinars ($2,650) to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the National Action Charter referendum. Agence France-Presse linked payments to the 14 February demonstration plans.[8]

The next day, Bahrain Centre for Human Rights sent an open letter to the king urging him to avoid a "worst-case scenario".[67][82][83] On 13 February, authorities increased the presence of security forces in key locations such as shopping malls and set up a number of checkpoints.[67] Al Jazeera interpreted the move as "a clear warning against holding Monday's rally".[67] At night, police attacked a small group of youth who organized a protest in Karzakan after a wedding ceremony.[67] Small protests and clashes occurred in other locations as well, such as Diraz, Sitra, Bani Jamra and Tashan leading to minor injuries to both sides.[10]: 68

Timeline

Protests began on 14 February 2011,[77] but met immediate reaction from security forces. Over thirty protesters were reportedly injured and one was killed as Bahraini government forces used tear gas, rubber bullets and birdshot to break up demonstrations, but protests continued into the evening, drawing several hundred participants.[84] Most of the protesters were Shia Muslims, who make up the majority of Bahrain's population.[30][85] The next day, one person attending the funeral of the protester killed on 14 February was shot dead and 25 more were hurt when security officers opened fire on mourners.[86][87] The same day, thousands of protesters marched to the Pearl Roundabout in Manama and occupied it, setting up protest tents and camping out overnight.[88][89] Sunni activist Mohamed Albuflasa was secretly arrested by security forces after addressing the crowd,[90][91] making him the first political prisoner of the uprising.[92]

In the early morning of 17 February, security forces retook control of the roundabout, killing four protesters and injuring over 300 in the process.[31][32][93][94] Manama was subsequently placed under lockdown, with tanks and armed soldiers taking up positions around the capital city.[31][95] In response, Al Wefaq MPs, then the largest bloc, submitted their resignations from the lower house of the National Assembly of Bahrain.[10]: 75 The next morning over 50,000 took part in the funerals of victims.[96] In the afternoon, hundreds of them marched to Manama. When they neared the Pearl Roundabout, the army opened fire injuring dozens and fatally wounding one.[97] Troops withdrew from the Pearl Roundabout on 19 February, and protesters reestablished their camps there.[98][99] The crown prince assured protesters that they would be allowed to camp at the roundabout.[10]: 83

Subsequent days saw large demonstrations; on 21 February, a pro-government "Gathering of National Unity" drew tens of thousands,[10]: 86 [100] while on 22 February the number of protesters at the Pearl Roundabout peaked at over 150,000 after more than 100,000 protesters marched there.[10]: 88 On 25 February, a national day of mourning was announced and large anti-government marches were staged.[101] Participants were twice as much as those in the 22 February march,[102] estimated at about 40% of Bahraini citizens.[103] Three days later hundreds protested outside parliament demanding the resignation of all MPs.[104] As protests intensified toward the end of the month,[105] King Hamad was forced to offer concessions in the form of the release of political prisoners[106] and the dismissal of three government ministers.[107]

Protests continued into March, with the opposition expressing dissatisfaction with the government's response.[108] A counter-demonstration on 2 March was staged, reportedly the largest political gathering in Bahrain's history in support of the government.[109] The next day, two were reportedly injured in clashed between naturalized Sunnis and local Shia youths in Hamad Town,[10]: 117 [110] and police deployed tear gas to break up the clashes.[111] Tens of thousands staged two protests the following day, one in Manama and the other headed to state TV accusing it of reinforcing sectarian divides.[112] Protesters escalated their calls for the removal of Prime Minister Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa, in power since 1971, from office, gathering outside his office on 6 March.[113]

The next day three protests were staged; the first near the US embassy, the second outside the Ministry of Interior building and the third and longest in front of Bahrain Financial Harbour.[114] On 8 March, three hard-line Shia groups called for the abdication of the monarchy and the establishment of a democratic republic via peaceful means, while the larger Al Wefaq group continued demanding an elected government and a constitutional monarchy.[115] On 9 March, thousands protested near Manama's immigration office against naturalizing foreigners and recruiting them in security forces.[116]

Hard-liners escalated their moves staging a protest headed to the Royal Court in Riffa on 11 March. Thousands carrying flowers and flags participated, but were blocked by riot police. During the same day, tens of thousands participated in a march in Manama organized by Al Wefaq.[117] The following day, tens of thousands of protesters encircled another royal palace and unlike the previous day, the protest ended peacefully. The same day, U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates was conducting a visit to the country.[118]

On 13 March, the government reacted strongly, with riot police firing tear gas canisters and tearing down protest tents in the Pearl Roundabout and using tear gas and rubber bullets to disperse demonstrators in the financial district,[119] where they had been camping for over a week.[120] Witnesses reported that riot police were encircling Pearl Roundabout, the focal point of the protest movement, but the Ministry of Interior said they were aiming to the open the highway and asked protesters to "remain in the roundabout for their safety".[120] Thousands of protesters clashed with police forcing them to retreat.[121]

Meanwhile, 150 government supporters stormed the University of Bahrain where about 5,000 students were staging an anti-government protest.[122] Clashes occurred between the two groups using sharp objects and stones. Riot police intervened by firing tear gas, rubber bullets and sound bombs on opposition protesters. During the day, the General Federation of Workers Trade Unions in Bahrain called for a general strike and the crown prince announced a statement outlining seven principles to be discussed in the political dialogue, including "a parliament with full authority" and "a government that represents the will of the people".[10]: 128–9, 130

As police were overwhelmed by protesters who also blocked roads, the government of Bahrain requested help from neighbouring countries.[123] On 14 March, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) agreed to deploy Peninsula Shield Force troops to Bahrain. Saudi Arabia deployed about 1,000 troops with armoured support, and the United Arab Emirates deployed about 500 police officers. The forces crossed into Bahrain via the King Fahd Causeway. The purported reason of the intervention was to secure key installations.[124][125] According to the BBC, "The Saudis took up positions at key installations but never intervened directly in policing the demonstrators", though warned that they would deal with the protesters if Bahrain did not.[126] The intervention marked the first time an Arab government requested foreign help during the Arab Spring.[127] The opposition reacted strongly, calling it an occupation and a declaration of war, and pleaded for international help.[127][128]

State of emergency

On 15 March, King Hamad declared a three-month state of emergency.[127] Thousands of protesters marched to the Saudi embassy in Manama denouncing the GCC intervention,[127] while clashes between security officers using shotgun and demonstrators took place in various locations. The most violent were on Sitra island stretching throughout morning till afternoon resulting in two deaths and over 200 injuries among protesters and one death among police.[10]: 140 [127] Doctors at the Salmaniya Medical Complex said it was overwhelmed with injured and that some had bullet wounds.[127] Jeffrey D. Feltman, then the US Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs was sent to Bahrain to mediate between the two sides. Opposition parties said they accepted the US initiative while the government did not respond.[10]: 142–3

- 16 March crackdown

In the early morning of 16 March, over 5,000 security forces backed by tanks and helicopters stormed the Pearl Roundabout, where protesters had camped for about a month.[10]: 143 The number of protesters was much lower than that in previous days due to many of them returning to villages to protect their homes.[129] Intimidated by the amount of security forces, most protesters retreated from the location, while others decided to stay and were violently cleared within two hours.[130] Then, security forces cleared road blockades and the financial harbor, and moved to take control over Salmaniya hospital. They entered the hospital building with their sticks, shields, handguns and assault rifles after clearing the parking area,[10]: 144–5 and treated it as a crime scene.[131]: 31:50

Witnesses said ambulances were captured inside the hospital and some health workers were beaten. Unable to reach Salmaniya hospital, the wounded were taken to small clinics outside the capital, which were stormed by police soon after, prompting protesters to use mosques as field clinics. Then, the army moved to opposition strongholds where it set up a number of checkpoints and thousands of riot police entered, forcing people to retreat to their homes by nightfall.[131]: 32–5 The Al Wefaq party advised people to stay off the streets, avoid confrontations with security forces and stay peaceful after the army had announced a nighttime 12-hour curfew in Manama and banned all sorts of public gatherings.[130] Eight people had died that day, five by gunshot, one by birdshot and two police reportedly run over by an SUV.[10]: 144, 146–7

- Arrests and widening crackdown

By the early hours of 17 March, over 1,000 protesters had been arrested,[131]: 34:50 including seven leading opposition figures, among them Abduljalil al-Singace, Abdulwahab Hussain, Ibrahim Sharif and Hasan Mushaima.[132] In an interview with Al Jazeera before his arrest, the latter had claimed protesters were gunned down despite offering only non-violent civil resistance.[133][134] In response to the government's reaction to the protests, a number of top Shia officials submitted their resignations, including two ministers, four appointed MPs and a dozen judges.[135][136] Protesters in several villages ignored the curfew and gathered in streets only to be dispersed by security forces,[10]: 149 [133] which allowed funerals as the only means of public gathering.[131]: 45 Arrested protesters were taken to police stations where they were mistreated and verbally abused.[10]: 151

Later in the day, surgeon Ali al-Ekri was arrested from the still surrounded Salmaniya hospital and by April another 47 health workers had been arrested.[131]: 43 [132] Their case drew wide international attention.[137] Patients at the hospital reported getting beaten and verbally abused by security forces and staff said patients with protest related injuries were kept in wards 62 and 63 where they were held as captives, denied health care and beaten on daily basis to secure confessions.[131]: 35–6, 42 Physicians for Human Rights accused the government of violating medical neutrality[138] and Médecins Sans Frontières said injured protesters were denied medical care and that hospitals were used as baits to snare them. The government of Bahrain dismissed these reports as lacking any evidence[139] and said forces were only deployed in the hospital to keep order.[140]

On 18 March, the Pearl Monument in the middle of the Pearl Roundabout was demolished on government orders[141] and a worker died in process.[131]: 47 The government said the demolition was in order to erase "bad memories"[142] and "boost flow of traffic",[141] but the site remained cordoned by security forces.[143] Security checkpoints set up throughout the country were used to beat and arrest those perceived to be anti-government,[10]: 150 among them was Fadhila Mubarak arrested on 20 March due to listening to 'revolutionary' music.[144] On 22 March, the General trade union supported by Al Wefaq suspended the general strike[145] after it had announced extending it indefinitely two days previously.[10]: 155 Meanwhile, over a thousand mourners took part in funeral of a woman killed in crackdown in Manama and human rights activists reported that night raids on dissent activists had continued.[145]

A "day of rage" was planned across Bahrain on 25 March[146] in order to move daily village protests into main streets,[147] but was quickly squelched by government troops, while thousands were allowed to take part in funeral of a man killed by police birdshot where they chanted anti-government slogans.[146][148] During the month, hundreds had been chanting Allahu Akbar from their rooftops in the afternoon and night.[149] Pakistani workers, some of them working in security forces said they were living in fear as they were attacked by mobs who injured many and killed two of them earlier in the month.[10]: 370 [150] On 28 March, the government of Bahrain shunned a Kuwaiti mediation offer that was accepted by Al Wefaq[151] and briefly arrested leading blogger Mahmood Al-Yousif,[152] driving others to hide.[153] The BBC reported that the police's brutal handling of the protests had turned Bahrain into 'island of fear'.[154] By the end of the month, another four had died bringing the number of deaths in the month to nineteen.[10]: 429–31

Bahrain TV ran a campaign to name, punish and shame those who took part in the protest movement. Athletes were its first targets;[131]: 38 the Hubail brothers, A'ala and Mohamed were suspended and arrested along with 200 other sportsmen after being shamed on TV.[155][156] Other middle-class sectors were also targeted, including academics, businessmen, doctors, engineers, journalists and teachers.[157][158] The witch-hunt expanded to the social media where Bahrainis were called to identify faces for arrests. Those arrested were checked off, among them was Ayat Al-Qurmezi who had read a poem criticizing the king and prime minister at the Pearl Roundabout. She was subsequently released following international pressure.[131]: 38–42, 50

Aftermath

In April, as a part of the crackdown campaign,[159] the government moved to destroy Shia places of worship, demolishing thirty five mosques. Although many had been standing for decades, the government said they were illegally built,[131]: 45 and justified destroying some of them at night as to avoid hurting people's psychology.[159] Among the destroyed was the Amir Mohammed Braighi mosque in A'ali which was built more than 400 years ago.[159] On 2 April, following an episode on Bahrain TV alleging it had published false and fabricated news, Al-Wasat, a local newspaper was banned briefly and its editor Mansoor Al-Jamri replaced.[10]: 390 [160] The next day over 2,000 participated in a funeral procession in Sitra and chanted anti-government slogans, and in Manama opposition legislators staged a protest in front of United Nations building.[161]

On 9 April, human rights activist Abdulhadi al-Khawaja and his two sons-in-law were arrested.[162][163] His daughter Zainab who subsequently underwent a hunger strike to protest the arrests,[164] said al-Khawaja was bleeding after getting beaten unconscious during the arrest.[165] That month alone, four protesters had died due to torture in government custody including journalists Karim Fakhrawi and Zakariya Rashid Hassan al-Ashiri.[10]: 430 The government initially denied such reports[164] and accused human rights activist Nabeel Rajab of fabricating photos, however a HRW researcher and a BBC reporter who had seen one body prior to burial stated they were accurate.[166][167] Five prison guards were subsequently charged with a protesters death.[168]

On 14 April, the Ministry of Justice moved to ban opposition groups Al Wefaq and Islamic Action Society on charges of violating laws and damaging "social peace and national unity",[169] however following US criticism, the government of Bahrain retracted their decision saying they would wait for investigation results.[170] On 16 April, human rights lawyer Mohammed al-Tajer, who represented leading opposition figures, was himself arrested during a night raid.[171][172] On 28 April, a special military court known as the National Safety Court sentenced four protesters to death and three others to life prison over charges of premeditated murder of two policemen on 16 March.[173] The sentences were upheld by a military court of appeal the following month.[174]

Starting from March and throughout May, hundreds of workers including labour union leaders were fired from their jobs after the government had encouraged companies such as Gulf Air to do so.[10]: 353 [175] The main reasons for dismissals were absence during the one-week general strike, taking part in protests and public display of anti-government opinion.[10]: 331 Although the government and several companies said the strike was illegal, the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry stated it was "within... the law".[10]: 353 Some workers who underwent investigations said they were shown images associating them with protests.[10]: 334 Head of the Civil Service Bureau initially denied those reports, but few months later acknowledged that several hundred have been dismissed.[10]: 335 In total 2,464 private sector and 2,075 public sector employees were fired for a total of 4539.[10]: 341–54

On 2 May, authorities arrested two of Al Wefaq's resigned MPs, Matar Matar and Jawad Ferooz.[176] Later in the month, the king of Bahrain announced that the state of emergency would be lifted on 1 June,[177] half a month before the scheduled date.[178] Tanks, armoured vehicles and manned military checkpoints were still prevalent in Manama and a number of villages.[179] Small protests and clashes with security forces dispersing them quickly continued in the villages and residents reported living under siege.[180][181] Hate speech similar to that preceding the Rwandan genocide was reported in a pro-government newspaper which "compared Shiites to 'termites' that should be exterminated".[159][182]

The first hearing for 13 opposition leaders was held on 8 May before the special military Court of National Safety marking the first time they saw their families after weeks of solitary confinement and alleged torture.[183][184] On 17 May, two local journalists working for Deutsche Presse-Agentur and France 24 were briefly arrested and interrogated, and one of them reported getting mistreated.[185] The following day, nine policemen were injured in Nuwaidrat. The Gulf Daily News reported that police were run over after they had injured and captured a "rioter",[186] while Al Akhbar reported that police had fired on each other after a dispute, adding that this incident exposed the presence of Jordanian officers within Bahrain security forces.[citation needed]

On 31 May, the king of Bahrain called for a national dialogue to begin in July in order to resolve ongoing tensions.[187] However, the seriousness and effectiveness of the dialogue has been disputed by the opposition,[188][189] who referred to it disparagingly as a "chitchat room".[190] Human Rights Watch said opposition parties were marginalized in the dialogue as they were only given 15 seats out of 297 despite winning 55% of votes in 2010 election.[191]

On 1 June, protests erupted across Shia-dominated areas of Bahrain to demand the end of martial law as the state of emergency was officially lifted.[192] Protests continued through early June, with demonstrators marching around the destroyed Pearl Roundabout, but security forces battled back and regularly dispersed demonstrators.[193] The 2011 edition of the Bahrain Grand Prix, a major Formula One racing event, was officially cancelled as the uprising wore on.[194] On 11 June, protest was announced in advance but did not receive government permission, opposition supporters said. It was held in the Shi'ite district of Saar, west of the capital. Police did not stop up to 10,000 people who came to the rally, many in cars, said a Reuters witness. Helicopters buzzed overhead.[195]

On 13 June, Bahrain's rulers commenced the trials of 48 medical professionals, including some of the country's top surgeons, a move seen as the hounding of those who treated injured protesters during the popular uprising which was crushed by the military intervention of Saudi Arabia.[196] On 18 June, The Bahraini government decided to lift a ban on the largest opposition party.[197] On 22 June, the Bahraini government sent 21 opposition figures to be tried by a special security court[198] which sentenced 8 pro-democracy activists to life in prison for their role in the uprising.[199] Other defendants were sentenced to between two and fifteen years in jail.[200]

On 9 August, the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry announced that 137 detainees had been released, including Matar Matar and Jawad Fayrouz, Shia MPs from the Al-Wefaq opposition party.[201]

2012

According to the Gulf Daily News on 1 February 2012, King Hamad's media affairs adviser Nabeel Al Hamer revealed plans for new talks between the opposition and the government on his Twitter account. He said that talks with political societies "had already begun to pave the way clear for a dialogue that would lead to a united Bahrain". The move was supported by Al Wefaq National Islamic Society former MP Abduljalil Khalil, who said that the society was "ready for serious dialogue and this time had no preconditions". He reiterated that "People want serious reforms that reflect their will and what they really want for their future." However the National Unity Assembly board member Khalid Al Qoud said that his society would not participate in talks "until those behind the acts of violence were arrested".[202] The call for dialogue was echoed by Crown Prince Salman bin Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa, who backed the initiative.[203]

The Bahrain Debate is an initiative organised "by the youth for the youth" that brings together young people from across the spectrum of Bahraini society to debate the political and social problems confronting the country, and their solutions. The debate is not funded or organised by any political group.[203] "In light of what has happened in Bahrain, people need to express themselves in a constructive way and listen to others' views," said Ehsan Al Kooheji, one of the organisers. "The youth are the country's future because they have the power to change things. They are extremely dynamic and energetic but have felt that they don't have a platform to express their opinions."[204]

Bahraini independents worried that the island will slide into sectarian violence also began an effort to break the political stalemate between pro-government and opposition forces. Dr. Ali Fakhro, a former minister and ambassador "respected across the political spectrum", told Reuters that he hoped to get moderates from both sides together at a time when extremists are making themselves felt throughout the Gulf Arab state. Fakhro said the initiative, launched at a meeting on 28 January 2012, involved persuading opposition parties and pro-government groups meeting outside a government forum and agreeing on a list of basic demands for democratic reform. He launched the plan at a meeting of prominent Bahrainis with no official political affiliations or memberships, called the National Bahraini Meeting. A basic framework for discussion is the seven points for democratic reform announced by Crown Prince Salman in March 2011.[205]

Bahraini newspaper Al Ayam reported on 7 March 2012 that the government and the opposition political societies were approaching an agreement to start a dialogue towards reconciliation and reunifying the country.[206]

On 9 March 2012, hundreds of thousands protested in one of the biggest anti-government rallies to date. According to CNN, the march "filled a four-lane highway between Diraz and Muksha".[207] A Reuters photographer estimated the number to be over 100,000[39] while opposition activists estimated the number to be between 100,000[208] and 250,000.[209] Nabeel Rajab, president of the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights called the march "the biggest in our history".[39]

The march was called for by Sheikh Isa Qassim, Bahrain's top Shia cleric. Protesters called for the downfall of the King and the release of imprisoned political leaders. The protest ended peacefully, however hundreds of youths tried to march back to the site of the now demolished symbolic Pearl roundabout, and were dispersed by security forces with tear gas.[210]

On 10 April, seven policemen were injured when a homemade bomb exploded in Eker, the Ministry of the Interior said. The ministry blamed protesters for the attack.[211] This was followed on 19 October by the siege of Eker.

On 18 April, in the run-up to the scheduled 2012 Bahrain Grand Prix, a car used by Force India mechanics had been involved in a petrol bombing,[212] though there were no injuries or damage.[213] The team members had been travelling in an unmarked car[214] and were held up by an impromptu roadblock which they were unable to clear before a petrol bomb exploded nearby.[215] Protests and protesters sharply increased in the spotlight of international press for the Grand Prix, and to condemn the implicit endorsement of the government by Formula One.[216][217]

2013

Inspired by the Egyptian Tamarod Movement that played a role in the removal of President Mohamed Morsi, Bahraini opposition activists called for mass protests starting on 14 August, the forty second anniversary of Bahrain Independence Day under the banner Bahrain Tamarod.[52] The day also marked the two and half anniversary of the Bahraini uprising.[218] In response, the Ministry of Interior (MoI) warned against joining what it called "illegal demonstrations and activities that endanger security" and stepped up security measures.[219][220]

2014

On 3 March, a bomb blast by Shia protesters in the village of Al Daih killed 3 police officers. One of the police officers killed was an Emirati policeman from the Peninsula Shield Force. The two other officers killed were Bahraini policemen. 25 suspects were arrested in connection to the bombing. In response to the violence, the Cabinet of Bahrain designated various protest groups as terrorist organizations.[221]

Rajab was released from Jaw Prison in May 2014 after serving a two-year sentence on charges of "illegal gathering", "disturbing public order" and "calling for and taking part in demonstrations" in Manama "without prior notification".[222]

In November, the first parliamentary elections were held in Bahrain since the beginning of the protests despite boycotts held by the Shia-majority opposition.[223]

Protests has been met with tear gas and protests re-erupted in October 2014, as a new wave of demonstrations, and continued daily for years. Daily protests were held every day for 3 years, from 2011 to 2014.

Sheikh Ali Salman, the Secretary-General of Al-Wefaq National Islamic Society was arrested on December 28, 2014,[224] The case against Sheikh Ali Salman is based on recorded telephone conversations he had with the-then Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs of Qatar, Sheikh Hamad Bin Jassim Bin Jabr Al Thani, in 2011. On 4 November 2018, he was sentenced to life imprisonment after being convicted of trumped-up spying charges. Two other al-Wefaq members, Ali al-Aswad and Sheikh Hassan Sultan, were convicted in their absence during the same trial.[225]

2015

At the beginning of the year, thousands of demonstrators gathered after the arrest of the largest representative of the Bahraini opposition, Ali Salman, and demanded his release, but the police responded to the demonstrators by dispersing them with tear gas and rubber bombs.

The Bahraini Minister of Interior stated that "Bahrain is facing a new stage, and that the end of 2014 is considered an important and special security location in terms of the nature and diversity of events and how they affect the security situation."

This was followed by the ruling on the head of the Shura Council of Al-Wefaq Society, Jamil Kazem, for a period of six months

A six-month prison sentence was also issued against the president of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights, Nabeel Rajab, with a fine of 200 Bahraini dinars in exchange for a stay of execution pending the appeal of the verdict.

Before the end of January, the authorities issued a decree revoking the citizenship of 72 Bahraini citizens, including activists, media professionals and writers living abroad.

The authority changed the location of two mosques for Shiite Muslims and moved them to tens of meters, which angered the Shiites, who represent the majority of the population.

On the fourth anniversary of the Bahrain uprising, demonstrators came out in Shiite villages and raised pictures of Ali Salman and demanded his release. The authorities launched a campaign of arrests in response.

2016

The death sentence issued against Nimr Al-Nimr was carried out on the morning of 2 January 2016, and his execution coincided with the execution of 46 others in terrorism-related cases. The executions were carried out in 12 regions of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Al-Nimr was accused of "aiding terrorists" that led to protests in Qatif.[226] Demonstrations erupted in villages after the execution of Nimr al-Nimr.[227][228]

On 20 June 2016, a week after the government of Bahrain suspended the main Shia opposition party al-Wefaq, Isa Qassim was stripped of his Bahraini citizenship. An interior ministry statement accused Sheikh Isa Qassim of "using his position to serve foreign interests" and "promote sectarianism and violence". Announcing the move to strip him of his Bahraini citizenship, the interior ministry said the cleric had "adopted theocracy and stressed the absolute allegiance to the clergy". It added that he had been in continuous contact with "organisations and parties that are enemies of the kingdom". Bahrain's citizenship law allows for the cabinet to revoke the citizenship of anyone who "causes harm to the interests of the kingdom or behaves in a way inimical with the duty of loyalty to it". Due to persecution at the hands of the Sunni regime, in December 2018 he relocated to Iraq.[229]

After the revocation of Isa Qassim's citizenship, many people became angry. Protestors gathered at the house of Isa Qassim in Diraz. They chanted slogans, "Down down Hamad," "With our souls and blood, we will redeem you, Faqih."[230] It was the second site where demonstrators gather after the Pearl Roundabout, which was destroyed in February 2011. The protests continued for 337 days.

On 17 July, Al Wefaq Association was permanently dissolved.[231]

2017

At the beginning of the year on Sunday, the Bahraini Ministry of Interior announced that gunmen had launched an attack on Juw prison in Bahrain, which resulted in "the escape of a number of convicts in terrorist cases" and the killing of a policeman.[232] On January 9, the ministry said that it had thwarted an escape operation by terrorist elements who tried to escape to Iran, and the operation led to the killing of three of the fugitives and the arrest of others.

On 15 January 2017, the Cabinet of Bahrain passed a capital punishment sentence of execution by firing squad on three men found guilty for the bomb attack in 2014 that killed three security forces.[233]

In the early morning of Thursday, January 26, 2017, the militias of the so-called National Security Apparatus launched an attack on the protesters in front of the house of Ayatollah Sheikh Isa Ahmed Qassim in the Diraz area, which led to the injury of one person with a serious head injury, and he died on Friday, March 24.

On May 23, the mercenary forces of the regime attacked again the demonstrators in front of the house of Isa Qassim, with a violent campaign that dispersed all the demonstrators, injuring dozens and killing 5 people. And the Ministry of Interior issued a statement saying that the forces arrested 286 people, saying that they were violators, and many of them are wanted and dangerous, and convicted of terrorist cases.[234]

The government of Bahrain forcibly closed Al-Wasat newspaper on 4 June 2017, in a move which Amnesty International termed an "all-out campaign to end independent reporting".[235]

2018

On the morning of Wednesday, February 7, 2018, four young men drowned in the territorial waters between Bahrain and the Islamic Republic of Iran in mysterious circumstances while trying to flee to the Islamic Republic. The bodies of three of them were found on February 15 and the other on March 5, and they were buried in Qom.

Bahrain government revoked the citizenship of 115 people and handed 53 of them life sentences on terrorism-related charges. Since 2012, a total of 718 individuals have been stripped of their Bahraini nationality, including 231 since the beginning of 2018. In most cases these individuals were rendered stateless. Some have subsequently been forcibly expelled from Bahrain.[236]

Hakeem al-Araibi was arrested on arrival in Thailand from Australia for a vacation in November 2018 on the basis of an Interpol "red notice" issued by Bahrain, and was held there pending deportation to Bahrain, which he opposed. There was a campaign urging Thailand not to extradite him until 11 February 2019, when the Thai Office of the Attorney-General dropped the extradition case against him at Bahrain's request. He was returned to Australia the next day and became an Australian citizen in the weeks thereafter. His case was widely reported on major news outlets throughout the world.[237][238][239]

2019

On April 16, A Bahraini court today convicted 139 people on terrorism charges in a mass trial involving a total of 169 defendants, sentencing them to prison terms of between three years and life in prison. In total, 138 of those convicted were arbitrarily stripped of their citizenship, and a further 30 were acquitted. "This trial also demonstrates how Bahrain's authorities are increasingly relying on revocation of nationality as a tool for repression – around 900 people have now been stripped of their citizenship since 2012.[240]

The authorities executed two Bahrainis convicted of "terrorism" by firing squad at dawn on Saturday, July 27, as announced by the Kingdom's Public Prosecutor in a statement, while a third convict was executed in a separate murder case. The Public Prosecutor did not mention the names of the two Bahrainis, while human rights organizations had said that they were Ali Al-Arab (25 years) and Ahmed Al-Malali (24 years), calling for a suspension of the execution of the sentence against them. Judicial sources stated that they are from the Shiite sect. The attorney general's statement stated that the subject of the first case was "focused on joining a terrorist group, committing murder and possessing explosives and firearms in fulfillment of a terrorist purpose." The persons concerned were arrested in February 2017, and sentences were issued against them on January 31, 2018, and since then they have exhausted all appeals.[241]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Bahraini_uprising_(2011–present)Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk