A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| History of art |

|---|

African art describes the modern and historical paintings, sculptures, installations, and other visual culture from native or indigenous Africans and the African continent. The definition may also include the art of the African diasporas, such as: African-American, Caribbean or art in South American societies inspired by African traditions. Despite this diversity, there are unifying artistic themes present when considering the totality of the visual culture from the continent of Africa.[2]

Pottery, metalwork, sculpture, architecture, textile art and fiber art are important visual art forms across Africa and may be included in the study of African art. The term "African art" does not usually include the art of the North African areas along the Mediterranean coast, as such areas had long been part of different traditions. For more than a millennium, the art of such areas had formed part of Berber or Islamic art, although with many particular local characteristics.

Ethiopian art, with a long Christian tradition,[3] is also different from that of most of Africa, where the Traditional African religion (with Islam in the north) was dominant until the 20th century.[4] African art includes prehistoric and ancient art, the Islamic art of West Africa, the Christian art of East Africa, and the traditional artifacts of these and other regions. Many African sculptures were historically made of wood and other natural materials that have not survived from earlier than a few centuries ago, although rare older pottery and metal figures can be found in some areas.[5] Some of the earliest decorative objects, such as shell beads and evidence of paint, have been discovered in Africa, dating to the Middle Stone Age.[6][7][8] Masks are important elements in the art of many peoples, along with human figures, and are often highly stylized. There is a vast variety of styles, often varying within the same context of origin and depending on the use of the object, but wide regional trends are apparent; sculpture is most common among "groups of settled cultivators in the areas drained by the Niger and Congo rivers" in West Africa.[9] Direct images of deities are relatively infrequent, but masks in particular are or were often made for ritual ceremonies. Since the late 19th century there has been an increasing amount of African art in Western collections, the finest pieces of which are displayed as part of the history of colonization.

African art has had an important influence on European Modernist art,[10] which was inspired by their interest in abstract depiction. It was this appreciation of African sculpture that has been attributed to the very concept of "African art", as seen by European and American artists and art historians.[11]

West African cultures developed bronze casting for reliefs, like the famous Benin Bronzes, to decorate palaces and for highly naturalistic royal heads from around the Bini town of Benin City, Edo State, as well as in terracotta or metal, from the 12th–14th centuries. Akan gold weights are a form of small metal sculptures produced over the period 1400–1900; some represent proverbs, contributing a narrative element rare in African sculpture; and royal regalia included gold sculptured elements.[12] Many West African figures are used in religious rituals and are often coated with materials placed on them for ceremonial offerings. The Mande-speaking peoples of the same region make pieces from wood with broad, flat surfaces and arms and legs shaped like cylinders. In Central Africa, however, the main distinguishing characteristics include heart-shaped faces that are curved inward and display patterns of circles and dots.

Thematic elements

- In Western African art, there is a focus on being expressive and unique while still being influenced by the art of those who came before. The art of the Dan people is an example of this, and it has also spread to Western African communities outside of the continent.[13]

- Emphasis on the human figure: The human figure has always been the primary subject matter for most African art, and this emphasis even influenced certain European traditions.[10] For example, in the fifteenth century, Portugal traded with the Sapi culture near the Ivory Coast in West Africa, who created elaborate ivory saltcellars that were hybrids of African and European designs, most notably in the addition of the human figure (the human figure typically did not appear in Portuguese saltcellars). The human figure may symbolize the living or the dead, may reference chiefs, dancers, or various trades or even may be an anthropomorphic representation of a god or have other votive functions. Another common theme is the inter-morphosis of humans and animals.

- Visual abstraction: African artworks tend to favour visual abstraction over naturalistic representation. This is because many African artworks generalize stylistic norms.[14]

Scope

The study of African art until recently focused on the traditional art of certain well-known groups on the continent, with a particular emphasis on traditional sculpture, masks and other visual culture from non-Islamic West Africa, Central Africa,[15] and Southern Africa with a particular emphasis on the 19th and 20th centuries. Recently, however, there has been a movement among African art historians and other scholars to include the visual culture of other regions and time periods. The notion is that by including all African cultures and their visual culture over time in African art, there will be a greater understanding of the continent's visual aesthetics across time. Finally, the arts of the people of the African diaspora, in Brazil, the Caribbean and the south-eastern United States, have also begun to be included in the study of African art.

Materials

African art is produced using a wide range of materials and takes many distinct shapes. Because wood is a very common material, wood sculptures make up the majority of African art. Other materials used in creating African arts includes clay soil. Jewelry is a popular art form and is used to indicate rank, affiliation with a group, or purely aesthetics.[16] African jewellery is made from such diverse materials as Tiger's eye stone, haematite, sisal, coconut shell, beads and ebony wood. Sculptures can be wooden, ceramic or carved out of stone like the famous Shona sculptures,[17] and decorated or sculpted pottery comes from many regions. Various forms of textiles are made including chitenge, mud cloth and kente cloth. Mosaics made of butterfly wings or colored sand are popular in West Africa. Early African sculptures can be identified as being made of terracotta and bronze.[18]

Traditional African religions

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2018) |

Traditional African religions have been extremely influential on African art forms across the continent. African art often stems from the themes of religious symbolism, functionalism and utilitarianism, and many pieces of art are created for spiritual rather than purely creative purposes. Many African cultures emphasize the importance of ancestors as intermediaries between the living, the gods, and the supreme creator, and art is seen as a way to contact these spirits of ancestors. Art may also be used to depict gods, and is valued for its functional purposes.[19] However, it is important to note that the arrival of both Christianity and Islam have also greatly influenced the art of the African continent, and traditions of both have been integrated into the beliefs and artwork of traditional African religion.[20]

History

The origins of African art lie long before recorded history. The region's oldest known beads were made from Nassarius shells and worn as personal ornaments 72,000 years ago.[6] In Africa, evidence for the making of paints by a complex process exists from about 100,000 years ago[7] and of the use of pigments from around 320,000 years ago.[8][21] African rock art in the Sahara in Niger preserves 6000-year-old carvings.[22] Along with sub-Saharan Africa, the western cultural arts, ancient Egyptian paintings and artifacts, and indigenous southern crafts also contributed greatly to African art. Often depicting the abundance of surrounding nature, the art was often abstract interpretations of animals, plant life, or natural designs and shapes. The Nubian Kingdom of Kush in modern Sudan was in close and often hostile contact with Egypt, and produced monumental sculptures mostly derivative of styles that did not lead to the north. In West Africa, the earliest known sculptures are from the Nok culture which thrived between 1,500 BC and 500 AD in modern Nigeria, with clay figures typically with elongated bodies and angular shapes.

More complex methods of producing art were developed in sub-Saharan Africa around the 10th century, some of the most notable advancements include the bronze work of Igbo Ukwu and the terracotta and metalworks of Ile Ife Bronze and brass castings, often ornamented with ivory and precious stones, became highly prestigious in much of West Africa, sometimes being limited to the work of court artisans and identified with royalty, as with the Benin Bronzes.

Influence on Western art

During and after the 19th and 20th century colonial period, Westerners long characterized African art as "primitive." The term carries with it negative connotations of underdevelopment and poverty. Colonization during the nineteenth century set up a Western understanding hinged on the belief that African art lacked technical ability due to its low socioeconomic status.

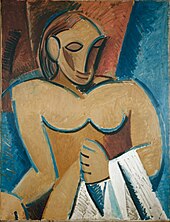

At the start of the twentieth century, art historians like Carl Einstein, Michał Sobeski and Leo Frobenius published important works about the thematic, giving African art the status of an aesthetic object, not only of an ethnographic object.[24] At the same time, artists like Paul Gauguin, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, André Derain, Henri Matisse, Joseph Csaky, and Amedeo Modigliani became aware of and inspired by, African art, amongst other art forms.[10] In a situation where the established avant-garde was straining against the constraints imposed by serving the world of appearances, African art demonstrated the power of supremely well-organized forms; produced not only by responding to the faculty of sight but also and often primarily, the faculty of imagination, emotion and mystical and religious experience. These artists saw in African art a formal perfection and sophistication unified with phenomenal expressive power. The study of and response to African art, by artists at the beginning of the twentieth century facilitated an explosion of interest in the abstraction, organisation and reorganization of forms, and the exploration of emotional and psychological areas hitherto unseen in Western art. By these means, the status of visual art was changed. Art ceased to be merely and primarily aesthetic, but became also a true medium for philosophic and intellectual discourse, and hence more truly and profoundly aesthetic than ever before.[25]

Traditional art

Traditional art describes the most popular and studied forms of African art which are typically found in museum collections.

Wooden masks, which might either be of human, animal or legendary creatures, are one of the most commonly found forms of art in Western Africa. In their original contexts, ceremonial masks are used for celebrations, initiations, crop harvesting, and war preparation. The masks are worn by a chosen or initiated dancer. During the mask ceremony the dancer goes into a deep trance, and during this state of mind he "communicates" with his ancestors. The masks can be worn in three different ways: vertically covering the face: as helmets, encasing the entire head, and as a crest, resting upon the head, which was commonly covered by material as part of the disguise. African masks often represent a spirit and it is strongly believed that the spirit of the ancestors possesses the wearer. Most African masks are made with wood, and can be decorated with: Ivory, animal hair, plant fibers (such as raffia), pigments (like kaolin), stones, and semi-precious gems also are included in the masks.

Statues, usually of wood or ivory, are often inlaid with cowrie shells, metal studs and nails. Decorative clothing is also commonplace and comprises another large part of African art. Among the most complex of African textiles is the colorful, strip-woven Kente cloth of Ghana. Boldly patterned mudcloth is another well known technique.

Contemporary African art

Africa is home to a thriving contemporary art and fine art culture. This has been understudied until recently, due to scholars' and art collectors' emphasis on traditional art. Notable modern artists include El Anatsui, Marlene Dumas, William Kentridge, Karel Nel, Kendell Geers, Yinka Shonibare, Zerihun Yetmgeta, Odhiambo Siangla, Elias Jengo, Olu Oguibe, Lubaina Himid, Bili Bidjocka and Henry Tayali. Art bienniales are held in Dakar, Senegal, and Johannesburg, South Africa. Many contemporary African artists are represented in museum collections, and their art may sell for high prices at art auctions. Despite this, many contemporary African artists tend to have a difficult time finding a market for their work. Many contemporary African arts borrow heavily from traditional predecessors. Ironically, this emphasis on abstraction is seen by Westerners as an imitation of European and American Cubist and totemic artists, such as Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani and Henri Matisse, who, in the early twentieth century, was heavily influenced by traditional African art. This period was critical to the evolution of Western modernism in visual arts, symbolized by Picasso's breakthrough painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.[26]

Today, Fathi Hassan is considered a major early representative of contemporary black African art. Contemporary African art was pioneered in the 1950s and 1960s in South Africa by artists like Irma Stern, Cyril Fradan, and Walter Battiss and through galleries like the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg. More recently European galleries such as the October Gallery in London and collectors such as Jean Pigozzi,[27] Artur Walther[28] and Gianni Baiocchi in Rome have helped expand the interest in the subject. Numerous exhibitions at the Museum for African Art in New York and the African Pavilion at the 2007 Venice Biennale, which showcased the Sindika Dokolo African

Collection of Contemporary Art, has gone a long way to counter many of the myths and prejudices that haunt Contemporary African Art. The appointment of Nigerian Okwui Enwezor as artistic director of Documenta 11 and his African-centred vision of art propelled the careers of countless African artists onto the international stage.

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk