A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| American Revolutionary War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolution | |||||||||

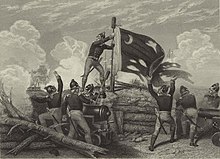

Clockwise from top left: Surrender of Lord Cornwallis after the Siege of Yorktown, Battle of Trenton, The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill, Battle of Long Island, and the Battle of Guilford Court House | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

|

Co-belligerents Limited support Combatants |

Co-belligerents | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a military conflict that was part of the broader American Revolution, where American Patriot forces organized as the Continental Army and commanded by George Washington defeated the British Army.

During the war, American Patriot forces had the support of France and Spain, while the British and Loyalist forces hired Hessian soldiers from Germany for assistance. The conflict was fought in North America, the Caribbean, and the Atlantic Ocean. The war ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which resulted in Great Britain ultimately recognizing the independence and sovereignty of the United States.

The American colonies were established by royal charter in the 17th and 18th centuries. After the British Empire gained dominance in North America with victory over the French in the Seven Years' War in 1763, tensions and disputes arose between Britain and the Thirteen Colonies over a variety of issues, including the Stamp and Townshend Acts. The resulting British military occupation led to the Boston Massacre in 1770, which strengthened American Patriots' desire for independence from Britain. Among further tensions, the British Parliament imposed the Intolerable Acts in mid-1774. A British attempt to disarm the Americans and the resulting Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775 ignited the war. In June, the Second Continental Congress formalized Patriot militias into the Continental Army and appointed Washington its commander-in-chief. The British Parliament declared the colonies to be in a state of rebellion in August 1775. The stakes of the war were formalized with passage of the Lee Resolution by the Congress in Philadelphia on July 2, 1776, and the unanimous ratification of the Declaration of Independence two days later, on July 4, 1776.

After a successful siege, Washington's forces drove the British Army out of Boston in March 1776, and British commander in chief William Howe responded by launching the New York and New Jersey campaign. Howe captured New York City in November. Washington responded by clandestinely crossing the Delaware River and winning small but significant victories at Trenton and Princeton, which restored Patriot confidence. In the summer of 1777, as Howe was poised to capture Philadelphia, the Continental Congress fled to Baltimore. In October 1777, a separate northern British force under the command of John Burgoyne was forced to surrender at Saratoga in an American victory that proved crucial in convincing France and Spain that an independent United States was a viable possibility. After Saratoga, France signed a commercial agreement with the rebels, followed by a Treaty of Alliance in February 1778. In 1779, the Sullivan Expedition undertook a scorched earth campaign against the Iroquois who were largely allied with the British. Indian raids on the American frontier, however, continued to be a problem. Also, in 1779, Spain allied with France against Britain in the Treaty of Aranjuez, though Spain did not formally ally with the Americans.

Howe's replacement Henry Clinton intended to take the war against the Americans into the south. Despite some initial success, British general Cornwallis was besieged by a Franco-American force in Yorktown in September and October 1781. Cornwallis was forced to surrender in October. The British wars with France and Spain continued for another two years, but fighting largely ceased in America. In April 1782, the North ministry was replaced by a new British government, which accepted American independence and began negotiating the Treaty of Paris, ratified on September 3, 1783. Britain acknowledged the sovereignty and independence of the United States of America, bringing the American Revolutionary War to an end. The Treaties of Versailles resolved Britain's conflicts with France and Spain and forced Great Britain to cede Tobago, Senegal, and small territories in India to France, and Menorca, West Florida and East Florida to Spain.[43][44]

Prelude to revolution

The French and Indian War, part of the wider global conflict known as the Seven Years' War, ended with the 1763 Peace of Paris, which expelled France from their possessions in New France.[45] Acquisition of territories in Atlantic Canada and West Florida, inhabited largely by French or Spanish-speaking Catholics, led British authorities to consolidate their hold by populating them with English-speaking settlers. Preventing conflict between settlers and Indian tribes west of the Appalachian Mountains also avoided the cost of an expensive military occupation.[46]

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was designed to achieve these aims by refocusing colonial expansion north into Nova Scotia and south into Florida, with the Mississippi River as the dividing line between British and Spanish possessions in America. Settlement was tightly restricted beyond the 1763 limits, and claims west of this line, including by Virginia and Massachusetts, were rescinded despite the fact that each colony argued that their boundaries extended from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean.[46]

The vast exchange of territory ultimately destabilized existing alliances and trade networks between settlers and Indians in the west, while it proved impossible to prevent encroachment beyond the Proclamation Line.[47] With the exception of Virginia and others deprived of rights to western lands, the colonial legislatures agreed on the boundaries but disagreed on where to set them. Many settlers resented the restrictions entirely, and enforcement required permanent garrisons along the frontier, which led to increasingly bitter disputes over who should pay for them.[48]

Taxation and legislation

Although directly administered by the Crown, acting through a local governor, the colonies were largely governed by native-born property owners. While external affairs were managed by London, colonial militia were funded locally but with the ending of the French threat in 1763, the legislatures expected less taxation, not more. At the same time, the huge debt incurred by the Seven Years' War and demands from British taxpayers for cuts in government expenditure meant Parliament expected the colonies to fund their own defense.[48]

The 1763 to 1765 Grenville ministry instructed the Royal Navy to cease trading smuggled goods and enforce customs duties levied in American ports.[48] The most important was the 1733 Molasses Act; routinely ignored before 1763, it had a significant economic impact since 85% of New England rum exports were manufactured from imported molasses. These measures were followed by the Sugar Act and Stamp Act, which imposed additional taxes on the colonies to pay for defending the western frontier.[49] In July 1765, the Whigs formed the First Rockingham ministry, which repealed the Stamp Act and reduced tax on foreign molasses to help the New England economy, but re-asserted Parliamentary authority in the Declaratory Act.[50]

However, this did little to end the discontent; in 1768, a riot started in Boston when the authorities seized the sloop Liberty on suspicion of smuggling.[51] Tensions escalated further in March 1770 when British troops fired on rock-throwing civilians, killing five in what became known as the Boston Massacre.[52] The Massacre coincided with the partial repeal of the Townshend Acts by the Tory-based North Ministry, which came to power in January 1770 and remained in office until 1781. North insisted on retaining duty on tea to enshrine Parliament's right to tax the colonies; the amount was minor, but ignored the fact it was that very principle Americans found objectionable.[53]

Tensions escalated following the destruction of a customs vessel in the June 1772 Gaspee Affair, then came to a head in 1773. A banking crisis led to the near-collapse of the East India Company, which dominated the British economy; to support it, Parliament passed the Tea Act, giving it a trading monopoly in the Thirteen Colonies. Since most American tea was smuggled by the Dutch, the act was opposed by those who managed the illegal trade, while being seen as yet another attempt to impose the principle of taxation by Parliament.[54] In December 1773, a group called the Sons of Liberty disguised as Mohawk natives dumped 342 crates of tea into the Boston Harbor, an event later known as the Boston Tea Party. The British Parliament responded by passing the so-called Intolerable Acts, aimed specifically at Massachusetts, although many colonists and members of the Whig opposition considered them a threat to liberty in general. This led to increased sympathy for the Patriot cause locally, in the British Parliament, and in the London press.[55]

Break with the British Crown

Throughout the 18th century, the elected lower houses in the colonial legislatures gradually wrested power from their royal governors.[56] Dominated by smaller landowners and merchants, these assemblies now established ad-hoc provincial legislatures, variously called congresses, conventions, and conferences, effectively replacing royal control. With the exception of Georgia, twelve colonies sent representatives to the First Continental Congress to agree on a unified response to the crisis.[57] Many of the delegates feared that an all-out boycott would result in war and sent a Petition to the King calling for the repeal of the Intolerable Acts.[58] However, after some debate, on September 17, 1774, Congress endorsed the Massachusetts Suffolk Resolves and on October 20 passed the Continental Association; based on a draft prepared by the First Virginia Convention in August, the association instituted economic sanctions and a full boycott of goods against Britain.[59]

While denying its authority over internal American affairs, a faction led by James Duane and future Loyalist Joseph Galloway insisted Congress recognize Parliament's right to regulate colonial trade.[59][u] Expecting concessions by the North administration, Congress authorized the extralegal committees and conventions of the colonial legislatures to enforce the boycott; this succeeded in reducing British imports by 97% from 1774 to 1775.[60] However, on February 9 Parliament declared Massachusetts to be in a state of rebellion and instituted a blockade of the colony.[61] In July, the Restraining Acts limited colonial trade with the British West Indies and Britain and barred New England ships from the Newfoundland cod fisheries. The increase in tension led to a scramble for control of militia stores, which each assembly was legally obliged to maintain for defense.[62] On April 19, a British attempt to secure the Concord arsenal culminated in the Battles of Lexington and Concord, which began the Revolutionary War.[63]

Political reactions

After the Patriot victory at Concord, moderates in Congress led by John Dickinson drafted the Olive Branch Petition, offering to accept royal authority in return for George III mediating in the dispute.[64] However, since the petition was immediately followed by the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms, Colonial Secretary Lord Dartmouth viewed the offer as insincere; he refused to present the petition to the king, which was therefore rejected in early September.[65] Although constitutionally correct, since George could not oppose his own government, it disappointed those Americans who hoped he would mediate in the dispute, while the hostility of his language annoyed even Loyalist members of Congress.[64] Combined with the Proclamation of Rebellion, issued on August 23 in response to the Battle at Bunker Hill, it ended hopes of a peaceful settlement.[66]

Backed by the Whigs, Parliament initially rejected the imposition of coercive measures by 170 votes, fearing an aggressive policy would simply drive the Americans towards independence.[67] However, by the end of 1774 the collapse of British authority meant both Lord North and George III were convinced war was inevitable.[68] After Boston, Gage halted operations and awaited reinforcements; the Irish Parliament approved the recruitment of new regiments, while allowing Catholics to enlist for the first time.[69] Britain also signed a series of treaties with German states to supply additional troops.[70] Within a year, it had an army of over 32,000 men in America, the largest ever sent outside Europe at the time.[71] The employment of German soldiers against people viewed as British citizens was opposed by many in Parliament and by the colonial assemblies; combined with the lack of activity by Gage, opposition to the use of foreign troops allowed the Patriots to take control of the legislatures.[72]

Declaration of Independence

Support for independence was boosted by Thomas Paine's pamphlet Common Sense, which was published on January 10, 1776, and argued for American self-government and was widely reprinted.[73] To draft the Declaration of Independence, the Second Continental Congress appointed the Committee of Five, consisting of Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston.[74] The declaration was written almost exclusively by Jefferson, who wrote it largely in isolation between June 11 and June 28, 1776, in a three-story residence at 700 Market Street in Philadelphia.[75]

Identifying inhabitants of the Thirteen Colonies as "one people", the declaration simultaneously dissolved political links with Britain, while including a long list of alleged violations of "English rights" committed by George III. This is also one of the foremost times that the colonies were referred to as "United States", rather than the more common United Colonies.[76]

On July 2, Congress voted for independence and published the declaration on July 4,[77] which George Washington read to his troops in New York City on July 9.[78] At this point, the revolution ceased to be an internal dispute over trade and tax policies and had evolved into a civil war, since each state represented in Congress was engaged in a struggle with Britain, but also split between American Patriots and American Loyalists.[79] Patriots generally supported independence from Britain and a new national union in Congress, while Loyalists remained faithful to British rule. Estimates of numbers vary, one suggestion being the population as a whole was split evenly between committed Patriots, committed Loyalists, and those who were indifferent.[80] Others calculate the split as 40% Patriot, 40% neutral, 20% Loyalist, but with considerable regional variations.[81]

At the onset of the war, the Second Continental Congress realized defeating Britain required foreign alliances and intelligence-gathering. The Committee of Secret Correspondence was formed for "the sole purpose of corresponding with our friends in Great Britain and other parts of the world". From 1775 to 1776, the committee shared information and built alliances through secret correspondence, as well as employing secret agents in Europe to gather intelligence, conduct undercover operations, analyze foreign publications, and initiate Patriot propaganda campaigns.[82] Paine served as secretary, while Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane, sent to France to recruit military engineers,[83] were instrumental in securing French aid in Paris.[84]

War breaks out

The Revolutionary War included two principal campaign theaters within the Thirteen Colonies, and a smaller but strategically important third one west of the Appalachian Mountains. Fighting began in the Northern Theater and was at its most severe from 1775 to 1778. American Patriots achieved several strategic victories in the South. The Americans defeated the British Army at Saratoga in October 1777, and the French, seeing the possibility for an American Patriot victory in the war, formally entered the war as an American ally.[85]

During 1778, Washington prevented the British army from breaking out of New York City, while militia under George Rogers Clark conquered Western Quebec, supported by Francophone settlers and their Indian allies, which became the Northwest Territory. The war became a stalemate in the north in 1779, so the British initiated their southern strategy, which aimed to mobilize Loyalist support in the region and occupy American Patriot-controlled territory north to Chesapeake Bay. The campaign was initially successful, with the British capture of Charleston being a major setback for southern Patriots; however, a Franco-American force surrounded the British army at Yorktown and their surrender in October 1781 effectively ended fighting in America.[80]

Early engagements

On April 14, 1775, Sir Thomas Gage, Commander-in-Chief, North America since 1763 and also Governor of Massachusetts from 1774, received orders to take action against the Patriots. He decided to destroy militia ordnance stored at Concord, Massachusetts, and capture John Hancock and Samuel Adams, who were considered the principal instigators of the rebellion. The operation was to begin around midnight on April 19, in the hope of completing it before the American Patriots could respond.[86][87] However, Paul Revere learned of the plan and notified Captain Parker, commander of the Concord militia, who prepared to resist the attempted seizure.[88] The first action of the war, commonly referred to as the shot heard round the world, was a brief skirmish at Lexington, followed by the full-scale Battles of Lexington and Concord. British troops suffered around 300 casualties before withdrawing to Boston, which was then besieged by the militia.[89]

In May 1775, 4,500 British reinforcements arrived under Generals William Howe, John Burgoyne, and Sir Henry Clinton.[90] On June 17, they seized the Charlestown Peninsula at the Battle of Bunker Hill, a frontal assault in which they suffered over 1,000 casualties.[91] Dismayed at the costly attack which had gained them little,[92] Gage appealed to London for a larger army to suppress the revolt,[93] but instead was replaced as commander by Howe.[91]

On June 14, 1775, Congress took control of American Patriot forces outside Boston, and Congressional leader John Adams nominated Washington as commander-in-chief of the newly formed Continental Army.[94] Washington previously commanded Virginia militia regiments in the French and Indian War,[95] and on June 16, Hancock officially proclaimed him "General and Commander in Chief of the army of the United Colonies."[96] He assumed command on July 3, preferring to fortify Dorchester Heights outside Boston rather than assaulting it.[97] In early March 1776, Colonel Henry Knox arrived with heavy artillery acquired in the Capture of Fort Ticonderoga.[98] Under cover of darkness, on March 5, Washington placed these on Dorchester Heights,[99] from where they could fire on the town and British ships in Boston Harbor. Fearing another Bunker Hill, Howe evacuated the city on March 17 without further loss and sailed to Halifax, Nova Scotia, while Washington moved south to New York City.[100]

Beginning in August 1775, American privateers raided towns in Nova Scotia, including Saint John, Charlottetown, and Yarmouth. In 1776, John Paul Jones and Jonathan Eddy attacked Canso and Fort Cumberland respectively. British officials in Quebec began negotiating with the Iroquois for their support,[101] while US envoys urged them to remain neutral.[102] Aware of Native American leanings toward the British and fearing an Anglo-Indian attack from Canada, Congress authorized a second invasion in April 1775.[103] After the defeat at the Battle of Quebec on December 31,[104] the Americans maintained a loose blockade of the city until they retreated on May 6, 1776.[105] A second defeat at Trois-Rivières on June 8 ended operations in Quebec.[106]

British pursuit was initially blocked by American naval vessels on Lake Champlain until victory at Valcour Island on October 11 forced the Americans to withdraw to Fort Ticonderoga, while in December an uprising in Nova Scotia sponsored by Massachusetts was defeated at Fort Cumberland.[107] These failures impacted public support for the Patriot cause,[108] and aggressive anti-Loyalist policies in the New England colonies alienated the Canadians.[109]

In Virginia, an attempt by Governor Lord Dunmore to seize militia stores on April 20, 1775, led to an increase in tension, although conflict was avoided for the time being.[110] This changed after the publication of Dunmore's Proclamation on November 7, 1775, promising freedom to any slaves who fled their Patriot masters and agreed to fight for the Crown.[111] British forces were defeated at Great Bridge on December 9 and took refuge on British ships anchored near the port of Norfolk. When the Third Virginia Convention refused to disband its militia or accept martial law, Dunmore ordered the Burning of Norfolk on January 1, 1776.[112]

The siege of Savage's Old Fields began on November 19 in South Carolina between Loyalist and Patriot militias,[113] and the Loyalists were subsequently driven out of the colony in the Snow Campaign.[114] Loyalists were recruited in North Carolina to reassert British rule in the South, but they were decisively defeated in the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge.[115] A British expedition sent to reconquer South Carolina launched an attack on Charleston in the Battle of Sullivan's Island on June 28, 1776,[116] but it failed and left the South under Patriot control until 1780.[117]

A shortage of gunpowder led Congress to authorize a naval expedition against the Bahamas to secure ordnance stored there.[118] On March 3, 1776, an American squadron under the command of Esek Hopkins landed at the east end of Nassau and encountered minimal resistance at Fort Montagu. Hopkins' troops then marched on Fort Nassau. Hopkins had promised governor Montfort Browne and the civilian inhabitants of the area that their lives and property would not be in any danger if they offered no resistance, to which they complied. Hopkins captured large stores of powder and other munitions that was so great he had to impress an extra ship in the harbor to transport the supplies back home, when he departed on March 17.[119] A month later, after a brief skirmish with HMS Glasgow, they returned to New London, Connecticut, the base for American naval operations during the Revolution.[120]

British New York counter-offensive

After regrouping at Halifax in Nova Scotia, Howe was determined to take the fight to the Americans.[121] He set sail for New York in June 1776 and began landing troops on Staten Island near the entrance to New York Harbor on July 2. The Americans rejected Howe's informal attempt to negotiate peace on July 30;[122] Washington knew that an attack on the city was imminent and realized that he needed advance information to deal with disciplined British regular troops.

On August 12, 1776, Patriot Thomas Knowlton was given orders to form an elite group for reconnaissance and secret missions. Knowlton's Rangers, which included Nathan Hale, became the Army's first intelligence unit.[123][v] When Washington was driven off Long Island, he soon realized that he would need more than military might and amateur spies to defeat the British. He was committed to professionalizing military intelligence. With aid from Benjamin Tallmadge, Washington launched the six-man Culper spy ring.[126][w] The efforts of Washington and the Culper Spy Ring substantially increased the effective allocation and deployment of Continental regiments in the field.[126] Throughout the war, Washington spent more than 10 percent of his total military funds on military intelligence operations.[127]

Washington split the Continental Army into positions on Manhattan and across the East River in western Long Island.[128] On August 27 at the Battle of Long Island, Howe outflanked Washington and forced him back to Brooklyn Heights, but he did not attempt to encircle Washington's forces.[129] Through the night of August 28, Knox bombarded the British. Knowing they were up against overwhelming odds, Washington ordered the assembly of a war council on August 29; all agreed to retreat to Manhattan. Washington quickly had his troops assembled and ferried them across the East River to Manhattan on flat-bottomed freight boats without any losses in men or ordnance, leaving General Thomas Mifflin's regiments as a rearguard.[130]

Howe met with a delegation from the Second Continental Congress at the September Staten Island Peace Conference, but it failed to conclude peace, largely because the British delegates only had the authority to offer pardons and could not recognize independence.[131] On September 15, Howe seized control of New York City when the British landed at Kip's Bay and unsuccessfully engaged the Americans at the Battle of Harlem Heights the following day.[132] On October 18, Howe failed to encircle the Americans at the Battle of Pell's Point, and the Americans withdrew. Howe declined to close with Washington's army on October 28 at the Battle of White Plains, and instead attacked a hill that was of no strategic value.[133]

Washington's retreat isolated his remaining forces and the British captured Fort Washington on November 16. The British victory there amounted to Washington's most disastrous defeat with the loss of 3,000 prisoners.[134] The remaining American regiments on Long Island fell back four days later.[135] General Henry Clinton wanted to pursue Washington's disorganized army, but he was first required to commit 6,000 troops to capture Newport, Rhode Island, to secure the Loyalist port.[136][x] General Charles Cornwallis pursued Washington, but Howe ordered him to halt, leaving Washington unmolested.[138]

The outlook following the defeat at Fort Washington appeared bleak for the American cause. The reduced Continental Army had dwindled to fewer than 5,000 men and was reduced further when enlistments expired at the end of the year.[139] Popular support wavered, and morale declined. On December 20, 1776, the Continental Congress abandoned the revolutionary capital of Philadelphia and moved to Baltimore, where it remained for over two months, until February 27, 1777.[140] Loyalist activity surged in the wake of the American defeat, especially in New York state.[141]

In London, news of the victorious Long Island campaign was well received with festivities held in the capital. Public support reached a peak,[142] and King George III awarded the Order of the Bath to Howe.[143] Strategic deficiencies among Patriot forces were evident: Washington divided a numerically weaker army in the face of a stronger one, his inexperienced staff misread the military situation, and American troops fled in the face of enemy fire. The successes led to predictions that the British could win within a year.[144] In the meantime, the British established winter quarters in the New York City area and anticipated renewed campaigning the following spring.[145]

Patriot resurgence

Two weeks after Congress withdrew to Baltimore, on the night of December 25–26, 1776, Washington crossed the Delaware River, leading a column of Continental Army troops from today's Bucks County, Pennsylvania, located about 30 miles upriver from Philadelphia, to today's Mercer County, New Jersey, in a logistically challenging and dangerous operation.

Meanwhile, the Hessians were involved in numerous clashes with small bands of Patriots and were often aroused by false alarms at night in the weeks before the actual Battle of Trenton. By Christmas they were tired and weary, while a heavy snowstorm led their commander, Colonel Johann Rall, to assume no attack of any consequence would occur.[146] At daybreak on the 26th, the American Patriots surprised and overwhelmed Rall and his troops, who lost over 20 killed including Rall,[147] while 900 prisoners, German cannons and much supply were captured.[148]

The Battle of Trenton restored the American army's morale, reinvigorated the Patriot cause,[149] and dispelled their fear of what they regarded as Hessian "mercenaries".[150] A British attempt to retake Trenton was repulsed at Assunpink Creek on January 2;[151] during the night, Washington outmaneuvered Cornwallis, then defeated his rearguard in the Battle of Princeton the following day. The two victories helped convince the French that the Americans were worthy military allies.[152]

After his success at Princeton, Washington entered winter quarters at Morristown, New Jersey, where he remained until May[153] and received Congressional direction to inoculate all Patriot troops against smallpox.[154][y] With the exception of a minor skirmishing between the two armies which continued until March,[156] Howe made no attempt to attack the Americans.[157]

British northern strategy fails

The 1776 campaign demonstrated that regaining New England would be a prolonged affair, which led to a change in British strategy. This involved isolating the north from the rest of the country by taking control of the Hudson River, allowing them to focus on the south where Loyalist support was believed to be substantial.[158] In December 1776, Howe wrote to the Colonial Secretary Lord Germain, proposing a limited offensive against Philadelphia, while a second force moved down the Hudson from Canada.[159] Germain received this on February 23, 1777, followed a few days later by a memorandum from Burgoyne, then in London on leave.[160]

Burgoyne supplied several alternatives, all of which gave him responsibility for the offensive, with Howe remaining on the defensive. The option selected required him to lead the main force south from Montreal down the Hudson Valley, while a detachment under Barry St. Leger moved east from Lake Ontario. The two would meet at Albany, leaving Howe to decide whether to join them.[160] Reasonable in principle, this did not account for the logistical difficulties involved and Burgoyne erroneously assumed Howe would remain on the defensive; Germain's failure to make this clear meant he opted to attack Philadelphia instead.[161]

Burgoyne set out on June 14, 1777, with a mixed force of British regulars, professional German soldiers and Canadian militia, and captured Fort Ticonderoga on July 5. As General Horatio Gates retreated, his troops blocked roads, destroyed bridges, dammed streams, and stripped the area of food.[162] This slowed Burgoyne's progress and forced him to send out large foraging expeditions; on one of these, more than 700 British troops were captured at the Battle of Bennington on August 16.[163] St Leger moved east and besieged Fort Stanwix; despite defeating an American relief force at the Battle of Oriskany on August 6, he was abandoned by his Indian allies and withdrew to Quebec on August 22.[164] Now isolated and outnumbered by Gates, Burgoyne continued onto Albany rather than retreating to Fort Ticonderoga, reaching Saratoga on September 13. He asked Clinton for support while constructing defenses around the town.[165]

Morale among his troops rapidly declined, and an unsuccessful attempt to break past Gates at the Battle of Freeman Farms on September 19 resulted in 600 British casualties.[166] When Clinton advised he could not reach them, Burgoyne's subordinates advised retreat; a reconnaissance in force on October 7 was repulsed by Gates at the Battle of Bemis Heights, forcing them back into Saratoga with heavy losses. By October 11, all hope of escape had vanished; persistent rain reduced the camp to a "squalid hell" of mud and starving cattle, supplies were dangerously low and many of the wounded in agony.[167] Burgoyne capitulated on October 17; around 6,222 soldiers, including German forces commanded by General Friedrich Adolf Riedesel, surrendered their arms before being taken to Boston, where they were to be transported to England.[168]

After securing additional supplies, Howe made another attempt on Philadelphia by landing his troops in Chesapeake Bay on August 24.[169] He now compounded failure to support Burgoyne by missing repeated opportunities to destroy his opponent, defeating Washington at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, then allowing him to withdraw in good order.[170] After dispersing an American detachment at Paoli on September 20, Cornwallis occupied Philadelphia on September 26, with the main force of 9,000 under Howe based just to the north at Germantown.[171] Washington attacked them on October 4, but was repulsed.[172]

To prevent Howe's forces in Philadelphia being resupplied by sea, the Patriots erected Fort Mifflin and nearby Fort Mercer on the east and west banks of the Delaware respectively, and placed obstacles in the river south of the city. This was supported by a small flotilla of Continental Navy ships on the Delaware, supplemented by the Pennsylvania State Navy, commanded by John Hazelwood. An attempt by the Royal Navy to take the forts in the October 20 to 22 Battle of Red Bank failed;[173][174] a second attack captured Fort Mifflin on November 16, while Fort Mercer was abandoned two days later when Cornwallis breached the walls.[175] His supply lines secured, Howe tried to tempt Washington into giving battle, but after inconclusive skirmishing at the Battle of White Marsh from December 5 to 8, he withdrew to Philadelphia for the winter.[176]

On December 19, the Americans followed suit and entered winter quarters at Valley Forge; while Washington's domestic opponents contrasted his lack of battlefield success with Gates' victory at Saratoga,[177] foreign observers such as Frederick the Great were equally impressed with Germantown, which demonstrated resilience and determination.[178] Over the winter, poor conditions, supply problems and low morale resulted in 2,000 deaths, with another 3,000 unfit for duty due to lack of shoes.[179] However, Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben took the opportunity to introduce Prussian Army drill and infantry tactics to the entire Continental Army; he did this by training "model companies" in each regiment, who then instructed their home units.[180] Despite Valley Forge being only twenty miles away, Howe made no effort to attack their camp, an action some critics argue could have ended the war.[181]

Foreign intervention

Like his predecessors, French foreign minister Vergennes considered the 1763 Peace a national humiliation and viewed the war as an opportunity to weaken Britain. He initially avoided open conflict, but allowed American ships to take on cargoes in French ports, a technical violation of neutrality.[182] Although public opinion favored the American cause, Finance Minister Turgot argued they did not need French help to gain independence, and war was too expensive. Instead, Vergennes persuaded Louis XVI to secretly fund a government front company to purchase munitions for the Patriots, carried in neutral Dutch ships and imported through Sint Eustatius in the Caribbean.[183]

Many Americans opposed a French alliance, fearing to "exchange one tyranny for another", but this changed after a series of military setbacks in early 1776. As France had nothing to gain from the colonies reconciling with Britain, Congress had three choices; making peace on British terms, continuing the struggle on their own, or proclaiming independence, guaranteed by France. Although the Declaration of Independence in July 1776 had wide public support, Adams was among those reluctant to pay the price of an alliance with France, and over 20% of Congressmen voted against it.[184] Congress agreed to the treaty with reluctance and as the war moved in their favor increasingly lost interest in it.[185]

Silas Deane was sent to Paris to begin negotiations with Vergennes, whose key objectives were replacing Britain as the United States' primary commercial and military partner while securing the French West Indies from American expansion.[186] These islands were extremely valuable; in 1772, the value of sugar and coffee produced by Saint-Domingue on its own exceeded that of all American exports combined.[187] Talks progressed slowly until October 1777, when British defeat at Saratoga and their apparent willingness to negotiate peace convinced Vergennes only a permanent alliance could prevent the "disaster" of Anglo-American rapprochement. Assurances of formal French support allowed Congress to reject the Carlisle Peace Commission and insist on nothing short of complete independence.[188]

On February 6, 1778, France and the United States signed the Treaty of Amity and Commerce regulating trade between the two countries, followed by a defensive military alliance against Britain, the Treaty of Alliance. In return for French guarantees of American independence, Congress undertook to defend their interests in the West Indies, while both sides agreed not to make a separate peace; conflict over these provisions would lead to the 1798 to 1800 Quasi-War.[185] Charles III of Spain was invited to join on the same terms but refused, largely due to concerns over the impact of the Revolution on Spanish colonies in the Americas. Spain had complained on multiple occasions about encroachment by American settlers into Louisiana, a problem that could only get worse once the United States replaced Britain.[189]

Although Spain ultimately made important contributions to American success, in the Treaty of Aranjuez, Charles agreed only to support France's war with Britain outside America, in return for help in recovering Gibraltar, Menorca and Spanish Florida.[190] The terms were confidential since several conflicted with American aims; for example, the French claimed exclusive control of the Newfoundland cod fisheries, a non-negotiable for colonies like Massachusetts.[191] One less well-known impact of this agreement was the abiding American distrust of 'foreign entanglements'; the U.S. would not sign another treaty with France until their NATO agreement of 1949.[185] This was because the US had agreed not to make peace without France, while Aranjuez committed France to keep fighting until Spain recovered Gibraltar, effectively making it a condition of U.S. independence without the knowledge of Congress.[192]

To encourage French participation in the struggle for independence, the U.S. representative in Paris, Silas Deane promised promotion and command positions to any French officer who joined the Continental Army. Such as Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, whom Congress via Dean appointed a major general,[193][194] on July 31, 1777.[195]

When the war started, Britain tried to borrow the Dutch-based Scots Brigade for service in America, but pro-Patriot sentiment led the States General to refuse.[196] Although the Republic was no longer a major power, prior to 1774 they still dominated the European carrying trade, and Dutch merchants made large profits shipping French-supplied munitions to the Patriots. This ended when Britain declared war in December 1780, a conflict that proved disastrous to the Dutch economy.[197] The Dutch were also excluded from the First League of Armed Neutrality, formed by Russia, Sweden and Denmark in March 1780 to protect neutral shipping from being stopped and searched for contraband by Britain and France.[198]

The British government failed to take into account the strength of the American merchant marine and support from European countries, which allowed the colonies to import munitions and continue trading with relative impunity. While well aware of this, the North administration delayed placing the Royal Navy on a war footing for cost reasons; this prevented the institution of an effective blockade and restricted them to ineffectual diplomatic protests.[199] Traditional British policy was to employ European land-based allies to divert the opposition, a role filled by Prussia in the Seven Years' War; in 1778, they were diplomatically isolated and faced war on multiple fronts.[200]

Meanwhile, George III had given up on subduing America while Britain had a European war to fight.[201] He did not welcome war with France, but he believed the British victories over France in the Seven Years' War as a reason to believe in ultimate victory over France.[202] Britain could not find a powerful ally among the Great Powers to engage France on the European continent.[203] Britain subsequently changed its focus into the Caribbean theater,[204] and diverted major military resources away from America.[205]

Vergennes's colleague stated, "For her honour, France had to seize this opportunity to rise from her degradation ... If she neglected it, if fear overcame duty, she would add debasement to humiliation, and become an object of contempt to her own century and to all future peoples".[206]

Stalemate in the North

At the end of 1777, Howe resigned and was replaced by Sir Henry Clinton on May 24, 1778; with French entry into the war, he was ordered to consolidate his forces in New York.[205] On June 18, the British departed Philadelphia with the reinvigorated Americans in pursuit; the Battle of Monmouth on June 28 was inconclusive but boosted Patriot morale. Washington had rallied Charles Lee's broken regiments, the Continentals repulsed British bayonet charges, the British rear guard lost perhaps 50 per-cent more casualties, and the Americans held the field at the end of the day. That midnight, the newly installed Clinton continued his retreat to New York.[207]

A French naval force under Admiral Charles Henri Hector d'Estaing was sent to assist Washington; deciding New York was too formidable a target, in August they launched a combined attack on Newport, with General John Sullivan commanding land forces.[208] The resulting Battle of Rhode Island was indecisive; badly damaged by a storm, the French withdrew to avoid putting their ships at risk.[209] Further activity was limited to British raids on Chestnut Neck and Little Egg Harbor in October.[210]

In July 1779, the Americans captured British positions at Stony Point and Paulus Hook.[211] Clinton unsuccessfully tried to tempt Washington into a decisive engagement by sending General William Tryon to raid Connecticut.[212] In July, a large American naval operation, the Penobscot Expedition, attempted to retake Maine, then part of Massachusetts, but was defeated.[213]

Persistent Iroquois raids in New York and Pennsylvania led to the punitive Sullivan Expedition from July to September 1779. Involving more than 4,000 patriot soldiers, the scorched earth campaign destroyed more than 40 Iroquois villages and 160,000 bushels (4,000 mts) of maize, leaving the Iroquois destitute and destroying the Iroquois confederacy as an independent power on the American frontier. However, the military expedition did not result in peace. 5,000 Iroquois fled to Canada. Supplied and supported by the British, they continued their raids.[214][215][216]

During the winter of 1779–1780, the Continental Army suffered greater hardships than at Valley Forge.[217] Morale was poor, public support fell away in the long war, the Continental dollar was virtually worthless, the army was plagued with supply problems, desertion was common, and mutinies occurred in the Pennsylvania Line and New Jersey Line regiments over the conditions in early 1780.[218]

In June 1780, Clinton sent 6,000 men under Wilhelm von Knyphausen to retake New Jersey, but they were halted by local militia at the Battle of Connecticut Farms; although the Americans withdrew, Knyphausen felt he was not strong enough to engage Washington's main force and retreated.[219] A second attempt two weeks later ended in a British defeat at the Battle of Springfield, effectively ending their ambitions in New Jersey.[220] In July, Washington appointed Benedict Arnold commander of West Point; his attempt to betray the fort to the British failed due to incompetent planning, and the plot was revealed when his British contact John André was captured and later executed.[221] Arnold escaped to New York and switched sides, an action justified in a pamphlet addressed "To the Inhabitants of America"; the Patriots condemned his betrayal, while he found himself almost as unpopular with the British.[222]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=American_war_of_independenceText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk