A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Geography |

|---|

|

Geography (from Ancient Greek γεωγραφία geōgraphía; combining gê 'Earth' and gráphō 'write') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth.[1] Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding of Earth and its human and natural complexities—not merely where objects are, but also how they have changed and come to be. While geography is specific to Earth, many concepts can be applied more broadly to other celestial bodies in the field of planetary science.[2] Geography has been called "a bridge between natural science and social science disciplines."[3]

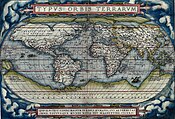

Origins of many of the concepts in geography can be traced to Greek Eratosthenes of Cyrene, who may have coined the term "geographia" (c. 276 BC – c. 195/194 BC).[4] The first recorded use of the word γεωγραφία was as the title of a book by Greek scholar Claudius Ptolemy (100 – 170 AD).[1] This work created the so-called "Ptolemaic tradition" of geography, which included "Ptolemaic cartographic theory."[5] However, the concepts of geography (such as cartography) date back to the earliest attempts to understand the world spatially, with the earliest example of an attempted world map dating to the 9th century BCE in ancient Babylon.[6] The history of geography as a discipline spans cultures and millennia, being independently developed by multiple groups, and cross-pollinated by trade between these groups. The core concepts of geography consistent between all approaches are a focus on space, place, time, and scale.[7][8][9][10][11][12]

Today, geography is an extremely broad discipline with multiple approaches and modalities. There have been multiple attempts to organize the discipline, including the four traditions of geography, and into branches.[13][3][14] Techniques employed can generally be broken down into quantitative[15] and qualitative[16] approaches, with many studies taking mixed-methods approaches.[17] Common techniques include cartography, remote sensing, interviews, and surveying.

Fundamentals

Geography is a systematic study of the Earth (other celestial bodies are specified, such as "geography of Mars", or given another name, such as areography in the case of Mars), its features, and phenomena that take place on it.[18][19][20] For something to fall into the domain of geography, it generally needs some sort of spatial component that can be placed on a map, such as coordinates, place names, or addresses. This has led to geography being associated with cartography and place names. Although many geographers are trained in toponymy and cartology, this is not their main preoccupation. Geographers study the Earth's spatial and temporal distribution of phenomena, processes, and features as well as the interaction of humans and their environment.[21] Because space and place affect a variety of topics, such as economics, health, climate, plants, and animals, geography is highly interdisciplinary. The interdisciplinary nature of the geographical approach depends on an attentiveness to the relationship between physical and human phenomena and their spatial patterns.[22]

Names of places...are not geography...To know by heart a whole gazetteer full of them would not, in itself, constitute anyone a geographer. Geography has higher aims than this: it seeks to classify phenomena (alike of the natural and of the political world, in so far as it treats of the latter), to compare, to generalize, to ascend from effects to causes, and, in doing so, to trace out the laws of nature and to mark their influences upon man. This is 'a description of the world'—that is Geography. In a word, Geography is a Science—a thing not of mere names but of argument and reason, of cause and effect.[23]

— William Hughes, 1863

Geography as a discipline can be split broadly into three main branches: human geography, physical geography, and technical geography.[3][24] Human geography largely focuses on the built environment and how humans create, view, manage, and influence space.[24] Physical geography examines the natural environment and how organisms, climate, soil, water, and landforms produce and interact.[25] The difference between these approaches led to the development of integrated geography, which combines physical and human geography and concerns the interactions between the environment and humans.[21] Technical geography involves studying and developing the tools and techniques used by geographers, such as remote sensing, cartography, and geographic information system.[26]

Key concepts

Narrowing down geography to a few key concepts is extremely challenging, and subject to tremendous debate within the discipline.[27] In one attempt, the 1st edition of the book "Key Concepts in Geography" broke down this into chapters focusing on "Space," "Place," "Time," "Scale," and "Landscape."[28] The 2nd edition of the book expanded on these key concepts by adding "Environmental systems," "Social Systems," "Nature," "Globalization," "Development," and "Risk," demonstrating how challenging narrowing the field can be.[27]

Another approach used extensively in teaching geography are the Five themes of geography established by "Guidelines for Geographic Education: Elementary and Secondary Schools," published jointly by the National Council for Geographic Education and the Association of American Geographers in 1984.[29][30] These themes are Location, place, relationships within places (often summarized as Human-Environment Interaction), movement, and regions[30][31] The five themes of geography have shaped how American education approaches the topic in the years since.[30][31]

Space

Just as all phenomena exist in time and thus have a history, they also exist in space and have a geography.[32]

For something to exist in the realm of geography, it must be able to be described spatially.[32][33] Thus, space is the most fundamental concept at the foundation of geography.[7][8] The concept is so basic, that geographers often have difficulty defining exactly what it is. Absolute space is the exact site, or spatial coordinates, of objects, persons, places, or phenomena under investigation.[7] We exist in space.[9] Absolute space leads to the view of the world as a photograph, with everything frozen in place when the coordinates were recorded. Today, geographers are trained to recognize the world as a dynamic space where all processes interact and take place, rather than a static image on a map.[7][34]

Place

Place is one of the most complex and important terms in geography.[9][10][11][12] In human geography, place is the synthesis of the coordinates on the Earth's surface, the activity and use that occurs, has occurred, and will occur at the coordinates, and the meaning ascribed to the space by human individuals and groups.[33][11] This can be extraordinarily complex, as different spaces may have different uses at different times and mean different things to different people. In physical geography, a place includes all of the physical phenomena that occur in space, including the lithosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere.[12] Places do not exist in a vacuum and instead have complex spatial relationships with each other, and place is concerned how a location is situated in relation to all other locations.[36][37] As a discipline then, the term place in geography includes all spatial phenomena occurring at a location, the diverse uses and meanings humans ascribe to that location, and how that location impacts and is impacted by all other locations on Earth.[11][12] In one of Yi-Fu Tuan's papers, he explains that in his view, geography is the study of Earth as a home for humanity, and thus place and the complex meaning behind the term is central to the discipline of geography.[10]

Time

Time is usually thought to be within the domain of history, however, it is of significant concern in the discipline of geography.[38][39][40] In physics, space and time are not separated, and are combined into the concept of spacetime.[41] Geography is subject to the laws of physics, and in studying things that occur in space, time must be considered. Time in geography is more than just the historical record of events that occurred at various discrete coordinates; but also includes modeling the dynamic movement of people, organisms, and things through space.[9] Time facilitates movement through space, ultimately allowing things to flow through a system.[38] The amount of time an individual, or group of people, spends in a place will often shape their attachment and perspective to that place.[9] Time constrains the possible paths that can be taken through space, given a starting point, possible routes, and rate of travel.[42] Visualizing time over space is challenging in terms of cartography, and includes Space-Prism, advanced 3D geovisualizations, and animated maps.[36][42][43][34]

Scale

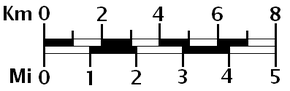

Scale in the context of a map is the ratio between a distance measured on the map and the corresponding distance as measured on the ground.[2][44] This concept is fundamental to the discipline of geography, not just cartography, in that phenomena being investigated appear different depending on the scale used.[45][46] Scale is the frame that geographers use to measure space, and ultimately to try and understand a place.[44]

Laws of geography

During the quantitative revolution, geography shifted to an empirical law-making (nomothetic) approach.[47][48] Several laws of geography have been proposed since then, most notably by Waldo Tobler and can be viewed as a product of the quantitative revolution.[49] In general, some dispute the entire concept of laws in geography and the social sciences.[36][50][51] These criticisms have been addressed by Tobler and others, such as Michael Frank Goodchild.[50][51] However, this is an ongoing source of debate in geography and is unlikely to be resolved anytime soon. Several laws have been proposed, and Tobler's first law of geography is the most generally accepted in geography. Some have argued that geographic laws do not need to be numbered. The existence of a first invites a second, and many have proposed themselves as that. It has also been proposed that Tobler's first law of geography should be moved to the second and replaced with another.[51] A few of the proposed laws of geography are below:

- Tobler's first law of geography: "Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant"[36][50][51]

- Tobler's second law of geography: "The phenomenon external to a geographic area of interest affects what goes on inside."[50][52]

- Arbia's law of geography: "Everything is related to everything else, but things observed at a coarse spatial resolution are more related than things observed at a finer resolution."[45][50][46][53][54]

- Spatial heterogeneity: Geographic variables exhibit uncontrolled variance.[51][55][56]

- The uncertainty principle: "That the geographic world is infinitely complex and that any representation must therefore contain elements of uncertainty, that many definitions used in acquiring geographic data contain elements of vagueness, and that it is impossible to measure location on the Earth's surface exactly."[51]

Additionally, several variations or amendments to these laws exist within the literature, although not as well supported. For example, one paper proposed an amendmended version of Tobler's first law of geography, referred to in the text as the Tobler–von Thünen law,[49] which states: "Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things, as a consequence of accessibility."[Note 1] [49]

Sub-disciplines

Geography is a branch of inquiry that focuses on spatial information on Earth. It is an extremely broad topic and can be broken down multiple ways.[14] There have been several approaches to doing this spanning at least several centuries, including "four traditions of geography" and into distinct branches.[57][13] The Four traditions of geography are often used to divide the different historical approaches theories geographers have taken to the discipline.[13] In contrast, geography's branches describe contemporary applied geographical approaches.[3]

Four traditions

Geography is an extremely broad field. Because of this, many view the various definitions of geography proposed over the decades as inadequate. To address this, William D. Pattison proposed the concept of the "Four traditions of Geography" in 1964.[13][58][59] These traditions are the Spatial or Locational Tradition, the Man-Land or Human-Environment Interaction Tradition (sometimes referred to as Integrated geography), the Area Studies or Regional Tradition, and the Earth Science Tradition.[13][58][59] These concepts are broad sets of geography philosophies bound together within the discipline. They are one of many ways geographers organize the major sets of thoughts and philosophies within the discipline.[13][58][59]

Branches

In another approach to the abovementioned four traditions, geography is organized into applied branches.[60][61] The UNESCO Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems organizes geography into the three categories of human geography, physical geography, and technical geography.[3][62][60][14] Some publications limit the number of branches to physical and human, describing them as the principal branches.[33] Geographers rarely focus on just one of these topics, often using one as their primary focus and then incorporating data and methods from the other branches. Often, geographers are asked to describe what they do by individuals outside the discipline[10] and are likely to identify closely with a specific branch, or sub-branch when describing themselves to lay people. Human geography studies people and their communities, cultures, economies, and environmental interactions by studying their relations with and across space and place.[33] Physical geography is concerned with the study of processes and patterns in the natural environment like the atmosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere, and geosphere.[33] Technical geography is interested in studying and applying techniques and methods to store, process, analyze, visualize, and use spatial data.[61] It is the newest of the branches, the most controversial, and often other terms are used in the literature to describe the emerging category. These branches use similar geographic philosophies, concepts, and tools and often overlap significantly.

Physical

Physical geography (or physiography) focuses on geography as an Earth science.[63][64][65] It aims to understand the physical problems and the issues of lithosphere, hydrosphere, atmosphere, pedosphere, and global flora and fauna patterns (biosphere). Physical geography is the study of earth's seasons, climate, atmosphere, soil, streams, landforms, and oceans.[66] Physical geographers will often work in identifying and monitoring the use of natural resources.

Human

Human geography (or anthropogeography) is a branch of geography that focuses on studying patterns and processes that shape human society.[67] It encompasses the human, political, cultural, social, and economic aspects. In industry, human geographers often work in city planning, public health, or business analysis.

Various approaches to the study of human geography have also arisen through time and include:

Technical

Technical geography concerns studying and developing tools, techniques, and statistical methods employed to collect, analyze, use, and understand spatial data.[26][3][60][62] Technical geography is the most recently recognized, and controversial, of the branches. Its use dates back to 1749, when a book published by Edward Cave organized the discipline into a section containing content such as cartographic techniques and globes.[57] There are several other terms, often used interchangeably with technical geography to subdivide the discipline, including "techniques of geographic analysis,"[68] "Geographic Information Technology,"[1] "Geography method's and techniques,"[69] "Geographic Information Science,"[70] "geoinformatics," "geomatics," and "information geography". There are subtle differences to each concept and term; however, technical geography is one of the broadest, is consistent with the naming convention of the other two branches, has been in use since the 1700s, and has been used by the UNESCO Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems to divide geography into themes.[3][60][57] As academic fields increasingly specialize in their nature, technical geography has emerged as a branch of geography specializing in geographic methods and thought.[26] The emergence of technical geography has brought new relevance to the broad discipline of geography by serving as a set of unique methods for managing the interdisciplinary nature of the phenomena under investigation. While human and physical geographers use the techniques employed by technical geographers, technical geography is more concerned with the fundamental spatial concepts and technologies than the nature of the data.[26][61] It is therefore closely associated with the spatial tradition of geography while being applied to the other two major branches. A technical geographer might work as a GIS analyst, a GIS developer working to make new software tools, or create general reference maps incorporating human and natural features.[71]

Methods

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2022) |

All geographic research and analysis start with asking the question "where," followed by "why there." Geographers start with the fundamental assumption set forth in Tobler's first law of geography, that "everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things."[36][37] As spatial interrelationships are key to this synoptic science, maps are a key tool. Classical cartography has been joined by a more modern approach to geographical analysis, computer-based geographic information systems (GIS).

In their study, geographers use four interrelated approaches:

- Analytical – Asks why we find features and populations in a specific geographic area.

- Descriptive – Simply specifies the locations of features and populations.

- Regional – Examines systematic relationships between categories for a specific region or location on the planet.

- Systematic – Groups geographical knowledge into categories that can be explored globally.

Quantitative methods

Quantitative methods in geography became particularly influential in the discipline during the quantitative revolution of the 1950s and 60s.[15] These methods revitalized the discipline in many ways, allowing scientific testing of hypotheses and proposing scientific geographic theories and laws.[72] The quantitative revolution heavily influenced and revitalized technical geography, and lead to the development of the subfield of quantitative geography.[26][15]

Quantitative cartography

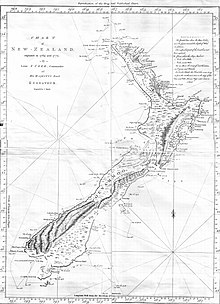

Cartography is the art, science, and technology of making maps.[73] Cartographers study the Earth's surface representation with abstract symbols (map making). Although other subdisciplines of geography rely on maps for presenting their analyses, the actual making of maps is abstract enough to be regarded separately.[74] Cartography has grown from a collection of drafting techniques into an actual science.

Cartographers must learn cognitive psychology and ergonomics to understand which symbols convey information about the Earth most effectively and behavioural psychology to induce the readers of their maps to act on the information. They must learn geodesy and fairly advanced mathematics to understand how the shape of the Earth affects the distortion of map symbols projected onto a flat surface for viewing. It can be said, without much controversy, that cartography is the seed from which the larger field of geography grew.

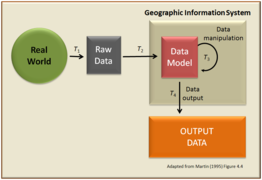

Geographic information systems

Geographic information systems (GIS) deal with storing information about the Earth for automatic retrieval by a computer in an accurate manner appropriate to the information's purpose.[75] In addition to all of the other subdisciplines of geography, GIS specialists must understand computer science and database systems. GIS has revolutionized the field of cartography: nearly all mapmaking is now done with the assistance of some form of GIS software. The science of using GIS software and GIS techniques to represent, analyse, and predict the spatial relationships is called geographic information science (GISc).[76]

Remote sensing

Remote sensing is the art, science, and technology of obtaining information about Earth's features from measurements made at a distance.[77] Remotely sensed data can be either passive, such as traditional photography, or active, such as LiDAR.[77] A variety of platforms can be used for remote sensing, including satellite imagery, aerial photography (including consumer drones), and data obtained from hand-held sensors.[77] Products from remote sensing include Digital elevation model and cartographic base maps. Geographers increasingly use remotely sensed data to obtain information about the Earth's land surface, ocean, and atmosphere, because it: (a) supplies objective information at a variety of spatial scales (local to global), (b) provides a synoptic view of the area of interest, (c) allows access to distant and inaccessible sites, (d) provides spectral information outside the visible portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, and (e) facilitates studies of how features/areas change over time. Remotely sensed data may be analyzed independently or in conjunction with other digital data layers (e.g., in a geographic information system). Remote sensing aids in land use, land cover (LULC) mapping, by helping to determine both what is naturally occurring on a piece of land and what human activities are taking place on it.[78]

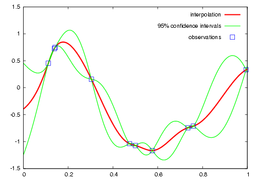

Geostatistics

Geostatistics deal with quantitative data analysis, specifically the application of a statistical methodology to the exploration of geographic phenomena.[79] Geostatistics is used extensively in a variety of fields, including hydrology, geology, petroleum exploration, weather analysis, urban planning, logistics, and epidemiology. The mathematical basis for geostatistics derives from cluster analysis, linear discriminant analysis and non-parametric statistical tests, and a variety of other subjects. Applications of geostatistics rely heavily on geographic information systems, particularly for the interpolation (estimate) of unmeasured points. Geographers are making notable contributions to the method of quantitative techniques.

Qualitative methods

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=GeographicalText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk