A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| English | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈɪŋɡlɪʃ/[1] |

| Native to | United Kingdom United States Canada Australia Ireland New Zealand other locations in the English-speaking world |

| Speakers | L1: 380 million (2021)[2] |

Early forms | |

| |

| Manually coded English (multiple systems) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Various organisations |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | en |

| ISO 639-2 | eng |

| ISO 639-3 | eng |

| Glottolog | stan1293 |

| Linguasphere | 52-ABA |

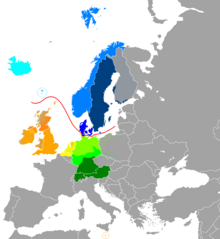

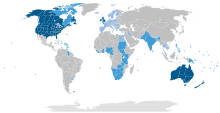

Countries and territories where English is the native language of the majority

Countries and territories where English is an official or administrative language but not a majority native language | |

| Part of a series on the |

| English language |

|---|

| Topics |

| Advanced topics |

| Phonology |

| Dialects |

|

| Teaching |

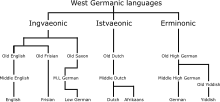

English is a West Germanic language in the Indo-European language family, whose speakers, called Anglophones, originated in early medieval England.[4][5][6] The namesake of the language is the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to the island of Great Britain.

English is the most spoken language in the world, primarily due to the global influences of the former British Empire (succeeded by the Commonwealth of Nations) and the United States.[7] English is the third-most spoken native language, after Mandarin Chinese and Spanish;[8] it is also the most widely learned second language in the world, with more second-language speakers than native speakers.

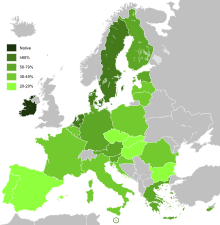

English is either the official language or one of the official languages in 59 sovereign states (such as India, Ireland, and Canada). In some other countries, it is the sole or dominant language for historical reasons without being explicitly defined by law (such as in the United States and United Kingdom).[9] It is a co-official language of the United Nations, the European Union, and many other international and regional organisations. It has also become the de facto lingua franca of diplomacy, science, technology, international trade, logistics, tourism, aviation, entertainment, and the internet.[10] English accounts for at least 70% of total speakers of the Germanic language branch, and as of 2005[update], it was estimated that there were over 2 billion speakers worldwide.[11]

Old English emerged from a group of West Germanic dialects spoken by the Anglo-Saxons. Late Old English borrowed some grammar and core vocabulary from Old Norse, a North Germanic language.[12][13][14] Then, Middle English borrowed words extensively from French dialects, which make up about 28% of Modern English vocabulary, and from Latin, which also provides about 28%.[15] As such, although most of its total vocabulary comes from Romance languages, its grammar, phonology, and most commonly used words keep it genealogically classified under the Germanic branch. English exists on a dialect continuum with Scots and is most closely related to the Low Saxon and Frisian languages.

Classification

English is an Indo-European language and belongs to the West Germanic group of the Germanic languages.[16] Old English originated from a Germanic tribal and linguistic continuum along the Frisian North Sea coast, whose languages gradually evolved into the Anglic languages in the British Isles, and into the Frisian languages and Low German/Low Saxon on the continent. The Frisian languages, which together with the Anglic languages form the Anglo-Frisian languages, are the closest living relatives of English. Low German/Low Saxon is also closely related, and sometimes English, the Frisian languages, and Low German are grouped together as the North Sea Germanic languages, though this grouping remains debated.[13] Old English evolved into Middle English, which in turn evolved into Modern English.[17] Particular dialects of Old and Middle English also developed into a number of other Anglic languages, including Scots[18] and the extinct Fingallian dialect and Yola language of Ireland.[19]

Like Icelandic and Faroese, the development of English in the British Isles isolated it from the continental Germanic languages and influences, and it has since diverged considerably. English is not mutually intelligible with any continental Germanic language, differing in vocabulary, syntax, and phonology, although some of these, such as Dutch or Frisian, do show strong affinities with English, especially with its earlier stages.[20]

Unlike Icelandic and Faroese, which were isolated, the development of English was influenced by a long series of invasions of the British Isles by other peoples and languages, particularly Old Norse and French dialects. These left a profound mark of their own on the language, so that English shows some similarities in vocabulary and grammar with many languages outside its linguistic clades—but it is not mutually intelligible with any of those languages either. Some scholars have argued that English can be considered a mixed language or a creole—a theory called the Middle English creole hypothesis. Although the great influence of these languages on the vocabulary and grammar of Modern English is widely acknowledged, most specialists in language contact do not consider English to be a true mixed language.[21][22]

English is classified as a Germanic language because it shares innovations with other Germanic languages such as Dutch, German, and Swedish.[23] These shared innovations show that the languages have descended from a single common ancestor called Proto-Germanic. Some shared features of Germanic languages include the division of verbs into strong and weak classes, the use of modal verbs, and the sound changes affecting Proto-Indo-European consonants, known as Grimm's and Verner's laws. English is classified as an Anglo-Frisian language because Frisian and English share other features, such as the palatalisation of consonants that were velar consonants in Proto-Germanic (see Phonological history of Old English § Palatalization).[24]

History

Overview of history

The earliest varieties of an English language, collectively known as Old English or "Anglo-Saxon", evolved from a group of North Sea Germanic dialects brought to Britain in the 5th century. Old English dialects were later influenced by Old Norse-speaking Viking invaders and settlers, starting in the 8th and 9th centuries. Middle English began in the late 11th century after the Norman Conquest of England, when a considerable amount of Old French vocabulary, was incorporated into English over some three centuries.[25][26]

Early Modern English began in the late 15th century with the start of the Great Vowel Shift and the Renaissance trend of borrowing further Latin and Greek words and roots, concurrent with the introduction of the printing press to London. This era notably culminated in the King James Bible and the works of William Shakespeare.[27][28] The printing press greatly standardised English spelling,[29] which has remained largely unchanged since then, despite a wide variety of later sound shifts in English dialects.

Modern English has spread around the world since the 17th century as a consequence of the worldwide influence of the British Empire and the United States. Through all types of printed and electronic media in these countries, English has become the leading language of international discourse and the lingua franca in many regions and professional contexts such as science, navigation, and law.[4] Its modern grammar is the result of a gradual change from a dependent-marking pattern typical of Indo-European with a rich inflectional morphology and relatively free word order to a mostly analytic pattern with little inflection and a fairly fixed subject–verb–object word order.[30] Modern English relies more on auxiliary verbs and word order for the expression of complex tenses, aspects and moods, as well as passive constructions, interrogatives, and some negation.

Proto-Germanic to Old English

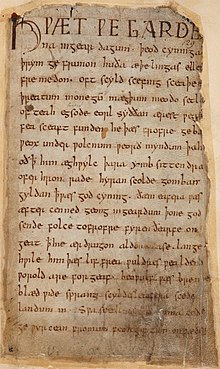

The earliest form of English is called Old English or Anglo-Saxon (c. 550–1066). Old English developed from a set of West Germanic dialects, often grouped as Anglo-Frisian or North Sea Germanic, and originally spoken along the coasts of Frisia, Lower Saxony and southern Jutland by Germanic peoples known to the historical record as the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes.[31] From the 5th century, the Anglo-Saxons settled Britain as the Roman economy and administration collapsed. By the 7th century, this Germanic language of the Anglo-Saxons became dominant in Britain, replacing the languages of Roman Britain (43–409): Common Brittonic, a Celtic language, and British Latin, brought to Britain by the Roman occupation.[32][33][34] At this time, these dialects generally resisted influence from the then-local Brittonic and Latin languages. England and English (originally Ænglaland and Ænglisc) are both named after the Angles.[35]

Old English was divided into four dialects: the Anglian dialects (Mercian and Northumbrian) and the Saxon dialects (Kentish and West Saxon).[36] Through the educational reforms of King Alfred in the 9th century and the influence of the kingdom of Wessex, the West Saxon dialect became the standard written variety.[37] The epic poem Beowulf is written in West Saxon, and the earliest English poem, Cædmon's Hymn, is written in Northumbrian.[38] Modern English developed mainly from Mercian, but the Scots language developed from Northumbrian. A few short inscriptions from the early period of Old English were written using a runic script.[39] By the 6th century, a Latin alphabet was adopted, written with half-uncial letterforms. It included the runic letters wynn ⟨ƿ⟩ and thorn ⟨þ⟩, and the modified Latin letters eth ⟨ð⟩, and ash ⟨æ⟩.[39][40]

Old English is essentially a distinct language from Modern English and is virtually impossible for 21st-century unstudied English-speakers to understand. Its grammar was similar to that of modern German: nouns, adjectives, pronouns, and verbs had many more inflectional endings and forms, and word order was much freer than in Modern English. Modern English has case forms in pronouns (he, him, his) and has a few verb inflections (speak, speaks, speaking, spoke, spoken), but Old English had case endings in nouns as well, and verbs had more person and number endings.[41][42][43] Its closest relative is Old Frisian, but even some centuries after the Anglo-Saxon migration, Old English retained considerable mutual intelligibility with other Germanic varieties. Even in the 9th and 10th centuries, amidst the Danelaw and other Viking invasions, there is historical evidence that Old Norse and Old English retained considerable mutual intelligibility,[44] although probably the northern dialects of Old English were more similar to Old Norse than the southern dialects. Theoretically, as late as the 900s AD, a commoner from certain (northern) parts of England could hold a conversation with a commoner from certain parts of Scandinavia. Research continues into the details of the myriad tribes in peoples in England and Scandinavia and the mutual contacts between them.[44]

The translation of Matthew 8:20 from 1000 shows examples of case endings (nominative plural, accusative plural, genitive singular) and a verb ending (present plural):

- Foxas habbað holu and heofonan fuglas nest

- Fox-as habb-að hol-u and heofon-an fugl-as nest-∅

- fox-NOM.PL have-PRS.PL hole-ACC.PL and heaven-GEN.SG bird-NOM.PL nest-ACC.PL

- "Foxes have holes and the birds of heaven nests"[45]

Influence of Old Norse

From the 8th to the 11th centuries, Old English gradually transformed through language contact with Old Norse in some regions. The waves of Norse (Viking) colonisation of northern parts of the British Isles in the 8th and 9th centuries put Old English into intense contact with Old Norse, a North Germanic language. Norse influence was strongest in the north-eastern varieties of Old English spoken in the Danelaw area around York, which was the centre of Norse colonisation; today these features are still particularly present in Scots and Northern English. The centre of Norsified English was in the Midlands around Lindsey. After 920 CE, when Lindsey was reincorporated into the Anglo-Saxon polity, English spread extensively throughout the region.

An element of Norse influence that continues in all English varieties today is the third person pronoun group beginning with th- (they, them, their) which replaced the Anglo-Saxon pronouns with h- (hie, him, hera).[46] Other core Norse loanwords include "give", "get", "sky", "skirt", "egg", and "cake", typically displacing a native Anglo-Saxon equivalent. Old Norse in this era retained considerable mutual intelligibility with some dialects of Old English, particularly northern ones.

Middle English

Englischmen þeyz hy hadde fram þe bygynnyng þre manner speche, Souþeron, Northeron, and Myddel speche in þe myddel of þe lond, ... Noþeles by comyxstion and mellyng, furst wiþ Danes, and afterward wiþ Normans, in menye þe contray longage ys asperyed, and som vseþ strange wlaffyng, chyteryng, harryng, and garryng grisbytting.

Although, from the beginning, Englishmen had three manners of speaking, southern, northern and midlands speech in the middle of the country, ... Nevertheless, through intermingling and mixing, first with Danes and then with Normans, amongst many the country language has arisen, and some use strange stammering, chattering, snarling, and grating gnashing.

John Trevisa, c. 1385[47]

Middle English is often arbitrarily defined as beginning with the conquest of England by William the Conqueror in 1066, but it developed further in the period from 1200 to 1450.

With the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the now-Norsified Old English language was subject to another wave of intense contact, this time with Old French, in particular Old Norman French. The Norman French spoken by the elite in England eventually developed into the Anglo-Norman language.[25] Because Norman was spoken primarily by the elites and nobles, while the lower classes continued speaking English, the main influence of Norman was the introduction of a wide range of loanwords related to politics, legislation and prestigious social domains.[14] Middle English also greatly simplified the inflectional system, probably in order to reconcile Old Norse and Old English, which were inflectionally different but morphologically similar. The distinction between nominative and accusative cases was lost except in personal pronouns, the instrumental case was dropped, and the use of the genitive case was limited to indicating possession. The inflectional system regularised many irregular inflectional forms,[48] and gradually simplified the system of agreement, making word order less flexible.[49]

In Wycliff'e Bible of the 1380s, the verse Matthew 8:20 was written: Foxis han dennes, and briddis of heuene han nestis.[50] Here the plural suffix -n on the verb have is still retained, but none of the case endings on the nouns are present. By the 12th century Middle English was fully developed, integrating both Norse and French features; it continued to be spoken until the transition to early Modern English around 1500. Middle English literature includes Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales, and Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur. In the Middle English period, the use of regional dialects in writing proliferated, and dialect traits were even used for effect by authors such as Chaucer.[51]

Early Modern English

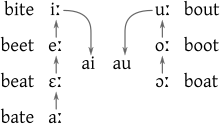

The next period in the history of English was Early Modern English (1500–1700). Early Modern English was characterised by the Great Vowel Shift (1350–1700), inflectional simplification, and linguistic standardisation.

The Great Vowel Shift affected the stressed long vowels of Middle English. It was a chain shift, meaning that each shift triggered a subsequent shift in the vowel system. Mid and open vowels were raised, and close vowels were broken into diphthongs. For example, the word bite was originally pronounced as the word beet is today, and the second vowel in the word about was pronounced as the word boot is today. The Great Vowel Shift explains many irregularities in spelling since English retains many spellings from Middle English, and it also explains why English vowel letters have very different pronunciations from the same letters in other languages.[52][53]

English began to rise in prestige, relative to Norman French, during the reign of Henry V. Around 1430, the Court of Chancery in Westminster began using English in its official documents, and a new standard form of Middle English, known as Chancery Standard, developed from the dialects of London and the East Midlands. In 1476, William Caxton introduced the printing press to England and began publishing the first printed books in London, expanding the influence of this form of English.[54] Literature from the Early Modern period includes the works of William Shakespeare and the translation of the Bible commissioned by King James I. Even after the vowel shift the language still sounded different from Modern English: for example, the consonant clusters /kn ɡn sw/ in knight, gnat, and sword were still pronounced. Many of the grammatical features that a modern reader of Shakespeare might find quaint or archaic represent the distinct characteristics of Early Modern English.[55]

In the 1611 King James Version of the Bible, written in Early Modern English, Matthew 8:20 says, "The Foxes haue holes and the birds of the ayre haue nests."[45] This exemplifies the loss of case and its effects on sentence structure (replacement with subject–verb–object word order, and the use of of instead of the non-possessive genitive), and the introduction of loanwords from French (ayre) and word replacements (bird originally meaning "nestling" had replaced OE fugol).[45]

Spread of Modern English

By the late 18th century, the British Empire had spread English through its colonies and geopolitical dominance. Commerce, science and technology, diplomacy, art, and formal education all contributed to English becoming the first truly global language. English also facilitated worldwide international communication.[27][4] English was adopted in parts of North America, parts of Africa, Oceania, and many other regions. When they obtained political independence, some of the newly independent states that had multiple indigenous languages opted to continue using English as the official language to avoid the political and other difficulties inherent in promoting any one indigenous language above the others.[56][57][58] In the 20th century the growing economic and cultural influence of the United States and its status as a superpower following the Second World War has, along with worldwide broadcasting in English by the BBC[59] and other broadcasters, caused the language to spread across the planet much faster.[60][61] In the 21st century, English is more widely spoken and written than any language has ever been.[62]

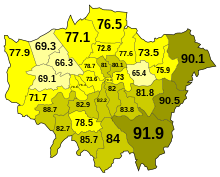

As Modern English developed, explicit norms for standard usage were published, and spread through official media such as public education and state-sponsored publications. In 1755 Samuel Johnson published his A Dictionary of the English Language, which introduced standard spellings of words and usage norms. In 1828, Noah Webster published the American Dictionary of the English language to try to establish a norm for speaking and writing American English that was independent of the British standard. Within Britain, non-standard or lower class dialect features were increasingly stigmatised, leading to the quick spread of the prestige varieties among the middle classes.[63]

In modern English, the loss of grammatical case is almost complete (it is now only found in pronouns, such as he and him, she and her, who and whom), and SVO word order is mostly fixed.[63] Some changes, such as the use of do-support, have become universalised. (Earlier English did not use the word "do" as a general auxiliary as Modern English does; at first it was only used in question constructions, and even then was not obligatory.[64] Now, do-support with the verb have is becoming increasingly standardised.) The use of progressive forms in -ing, appears to be spreading to new constructions, and forms such as had been being built are becoming more common. Regularisation of irregular forms also slowly continues (e.g. dreamed instead of dreamt), and analytical alternatives to inflectional forms are becoming more common (e.g. more polite instead of politer). British English is also undergoing change under the influence of American English, fuelled by the strong presence of American English in the media and the prestige associated with the United States as a world power.[65][66][67]

Geographical distribution

As of 2016[update], 400 million people spoke English as their first language, and 1.1 billion spoke it as a secondary language.[68] English is the largest language by number of speakers. English is spoken by communities on every continent and on islands in all the major oceans.[69]

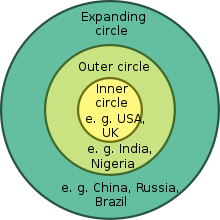

The countries where English is spoken can be grouped into different categories according to how English is used in each country. The "inner circle"[70] countries with many native speakers of English share an international standard of written English and jointly influence speech norms for English around the world. English does not belong to just one country, and it does not belong solely to descendants of English settlers. English is an official language of countries populated by few descendants of native speakers of English. It has also become by far the most important language of international communication when people who share no native language meet anywhere in the world.

Three circles of English-speaking countries

The Indian linguist Braj Kachru distinguished countries where English is spoken with a three circles model.[70] In his model,

- the "inner circle" countries have large communities of native speakers of English, Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=English_language

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk